For those in international shipping and trade, 2020 became the Year of Living Virtually as dozens of conferences and trade shows eschewed cancelling due to pandemic travel restrictions and opted for going digital. And the WCA World, a networking association of independent international freight forwarders, has taken this online technology one step farther, opening up a glimpse into a virtual world once imagined as science fiction rather than an everyday reality.

Virtual is a reality

For those companies engaged in international shipping and trade, 2020 became the Year of Living Virtually, as dozens of trade shows were cancelled due to pandemic initiated travel restrictions.

For the many businesses engaged in the international movement of goods, the cancellations represented a major blow to their annual business calendar. In many respects, these meetings were a critical part of a company’s annual planning: a chance to talk face-to-face with colleagues and competitors on the state-of-the-industry as well establishing new business links around the world.

In no aspect of shipping and trade are trade conferences and exhibitions more essential than to the international freight forwarding community – particularly the independent freight forwarders. International freight forwarders are the ultimate middle man in the global movement of goods. Forwarders are instrumental in providing compliance with the complex trade customs procedures and understanding of the transportation services of each nation in the supply chain. While the larger 3PLs are often the most visible face of international business, in reality the smaller independent forwarders are often the “gatekeepers” for trade for the nations with developing economies, which far outnumber top tier trading states.

Although technology has been instrumental in improving international trade flows, interpersonal relations between forwarding partners is still a key to tackling the inevitable problems that emerge. And that requires an element of trust between forwarders on each side of the transaction and establishing that bond often begins at trade conferences organized by freight forwarding networks.

Anatomy of a Virtual Conference

By far the largest of the global freight forwarding networks is the WCA World, an umbrella organization comprised of fifteen logistics networks accounting for around 9,500 member offices located in 194 countries. Founded by David Yokeum in 1998, the WCA World [wcaworld.com] has pioneered “networking” and in many respects has become the model emulated not only by other freight forwarding networks but other business sectors as well. Among the WCA’s innovations was the development of a sophisticated system of conferences. At their core, the WCA’s conferences are designed to provide a forum for “one-on-one” business meetings between members. But from a wider perspective, the gatherings enable the forwarders to meet informally to discuss industry issues. In the case of the WCA with conferences regularly attended by over 2,000 members, recreating the conference in a “virtual reality” setting was destined to be a challenge.

Dan March, CEO of WCA World, in an interview with the American Journal of Transportation, offered the anatomy of putting together the network’s complex undertaking. As March explained the situation, “In January [with the news of COVID-19’s global spread] we were already resigned that the [WCA’s] Worldwide meeting in Macao [scheduled for Dec. 2020] would be cancelled.” Even with the conference months out, WCA’s senior management were asking themselves questions the pandemic was creating worldwide like: “What if there is no travel?” “How can we protect the health of our members and our staff?”

For the WCA it was clear that the meetings would have to be “virtual”, but as March noted, they had seen a number of virtual meetings but nothing on the “scale of 3,500 members.” The immediate goal was to find the software meeting system to handle both the scale and style of a WCA conference. The WCA had chosen a US-based company to hold the virtual conferences and “We had the weak part of the calendar [smaller conferences ] to test the platform,” March said.

The WCA chose the GAA [Global Affinity Conference] as their first test on the new system in June with an expected attendance of around 300. The GAA test pointed out a number of problems, the biggest difficulty, according to March, was “coordinating scheduling…there were a number of failures,” adjusting to various time zones.

A New Approach

The test was enough to convince WCA management that they would have to develop their own virtual conference system to provide the scale and adaptability they’d need for hosting the WCA Worldwide Virtual Conference at the end of the year. The WCA, working with their own developers in the US and Thailand, came up with a new concept built less around the presentations by existing software and more around reverse engineering conference experience itself. March said the WCA found that third party software options, such as Zoom, could not offer the functionality and full experience they wanted to provide: “We wanted it to be an immersive experience” that mimicked attending a real conference.

This approach was a radical departure from the “conventional” teleconference and presented a number of significant technical and operational challenges.

From a technical point of view creating the “immersive experience” meant recreating the conference “virtually” yet keeping the process user friendly enough for a wide group of delegates with varying degrees of computer experience . Put another way, it had to be intuitive to use with little or no training. On the operational side, the overarching question, was whether the system was robust enough to handle the massive traffic that 2,000 plus members would generate. As March said, it was a question of “would the servers stand up.”

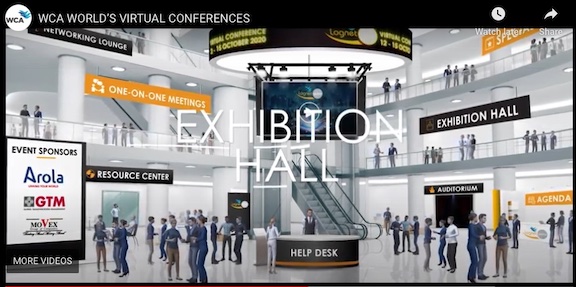

Among the many innovations in the WCA virtual conference was actual “feel”. The delegates “felt” like they were entering a real conference and could immediately go to a “help desk” to get the agenda for the meetings. The attendee has choices of which venues to visit – including a hall for “virtual” exhibitors. The virtual booth allows the delegate to pick up exhibitor information and even exchange business cards as well as set up meetings. According to the WCA post-conference data, around 40 companies setup virtual booths and had over 1,000 attendees visiting their booths for the video meetings and chats.

Another innovation was a “networking lounge” which allowed around 1,400 attendees to socialize and chat with each other and introduce new members. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of the conference experience to replicate is the ubiquitous “cocktail” meetings which are often the catalyst for further business discussions. The WCA tackled this unique challenge by creating a social gathering in the form of an informal virtual get-together with 5 minute random meetings.

The “guts” of any WCA conference is the one-on-one meetings. In a non-virtual world, they are set up in advance and the attendees move table to table for a set length of time to meet with the members on their one-on-one meeting sheets. The one-on-ones are carefully choregraphed which is easy [in a relative way] to do when everyone is under “one roof” but in a virtual world the attendees are spread over many time zones. For this reason, the conference was run 24 hours-per-day. With the proprietary system, a delegate could book up to 40 meetings per day. The final tally was over 26,000 one-on-one meetings were held between the 1,400 attendees spread over 4 and a half days with a success rate of over 80%.

With the experience of the four events, the WCA is gearing up for their Sino-International Freight Conference March 15-19, 2021[www.sinoconference.com]. The challenges of working with China’s “great firewall” poses some issues but in some ways, there is a side benefit to being able to virtually visit China. According to the WCA, the conference will be open to all independent logistics companies, alongside vendors such as airlines, IT companies, charter brokers and ports/airports. It is jointly co-hosted and organized with the China International Freight Forwarders’ Association (CIFFA), and will emphasize trade between China and the rest of the world. The event is expected to attract over 800 delegates.

A Virtual Post Mortem

The WCA’s “Worldwide” virtual conference answered the question of whether a large scale “virtual” conference was feasible, but what role will the “virtual” conference play when reality is re-established post-pandemic world?

Like many things, it comes down to money. While the WCA members reportedly saved over $5 million in travel, lodging and other fees, for an organization that raises a great deal of its annual revenue from events, going virtual while a practical alternative during the pandemic is no panacea to real-world conferencing.

But March believes there is a long term role for “virtual” in the trade conference business. Already the WCA is working to make the WCAworld Academy, which offers online and offline classroom based training, a flagship for a virtual business sector. And it is easy to see how two-day seminars with shorter run times could compliment a trade groups’ event portfolio - especially when the upfront expense of building a home grown platform has already been underwritten. But March cautioned that trade organizations have to “be careful offering virtual” as there is nothing quite as immersive as the real world.