Matt Muenster, Senior Manager of Applied Knowledge, Breakthrough

When emissions regulations are implemented for one mode of transportation, an hourglass turns over for other modes.

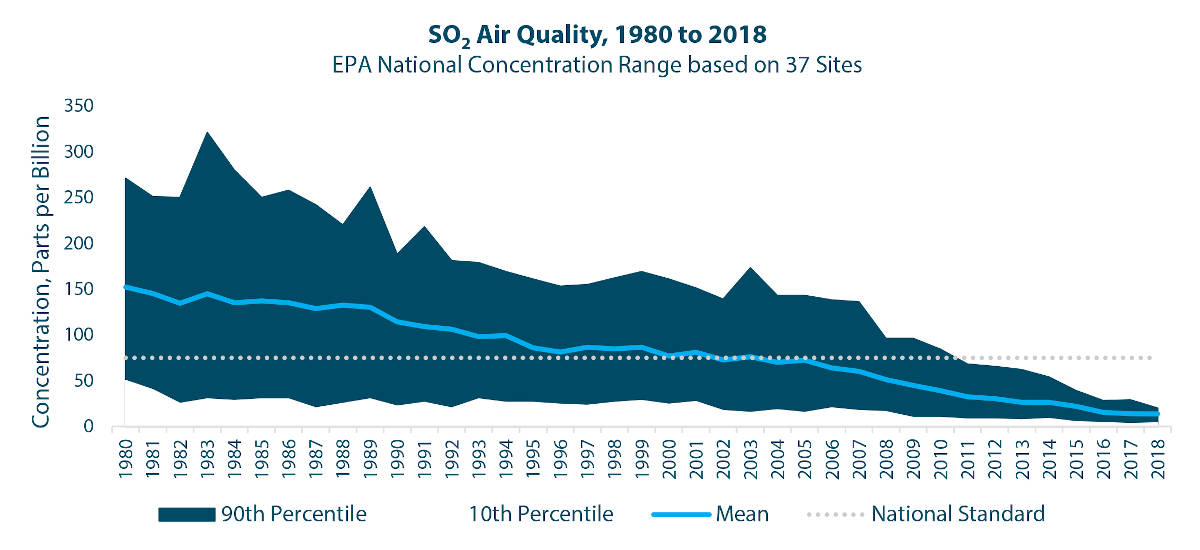

From a historical perspective, the full regulatory change brought about by IMO 2020 rippled from previous emissions regulations. The push to reduce the amount of allowable sulfur content in fuel started decades ago. As one example, the U.S. commercial trucking industry began its move toward ultra-low-sulfur diesel with lower sulfur tolerance beginning in the 1990s.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Air Act limited the trucking industry’s sulfur content limit of on-highway diesel fuel to 500 parts per million (ppm) beginning in 1993. This was already lower sulfur content than what the commercial maritime industry has transitioned to over 25 years later (5,000 ppm). Commercial trucking sulfur limits became even more aggressive in 2006, when the sulfur content of on-highway diesel fuel was limited to just 15 ppm.

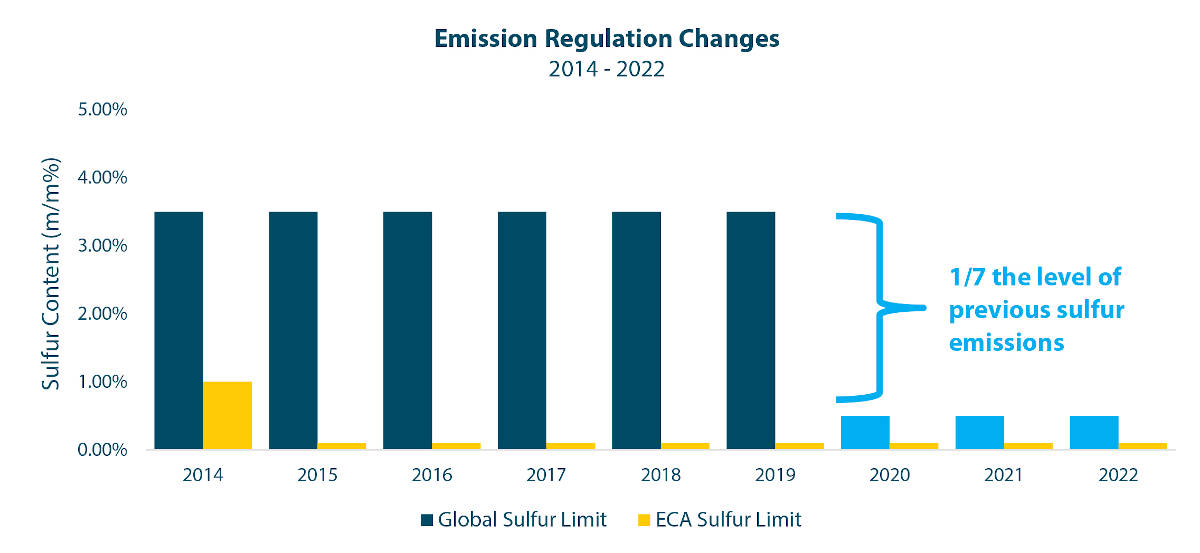

The initial push to dramatically decrease sulfur content in transport fuel did not stop with the trucking industry. The EPA’s limits later extended to nonroad fuel, including locomotive diesel fuel in 2012, and U.S. marine fuel soon after. In 2015, the IMO implemented the North American Emission Control Area (ECA) as part of an amendment to a 1997 protocol of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). MARPOL also helped us arrive to today; the post-Jan. 1, 2020 world with lower international maritime sulfur emissions.

The takeaway? The emissions that are cut for one mode of transportation are destined to be cut for another once their societal impact is understood.

Shippers Must Consider Their Exposure to Tightening Emissions Standards

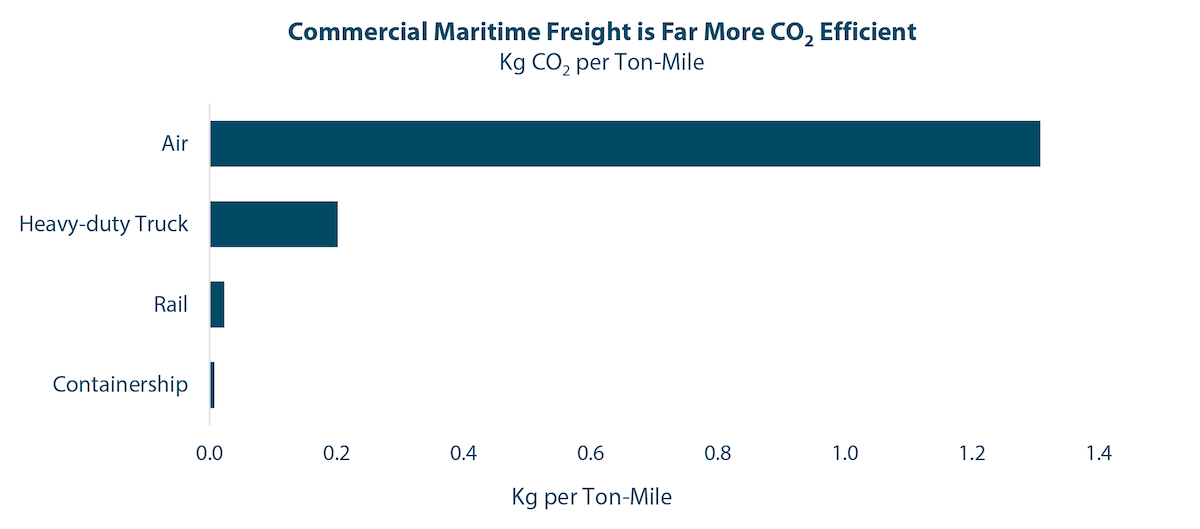

Climate change is firmly on public and corporate agendas, with plenty of implications for commercial transport. The next decade will see freight transportation grapple with accepting the costs of what has commonly been omitted from emissions regulations: carbon dioxide (CO2).

Ironically, the order of adoption for CO2 standards across modes of freight transportation will likely be chronologically backward from the experience with sulfur. The commercial maritime industry, through the IMO, has already adopted plans to reduce greenhouse gases (namely CO2) produced from shipping by 50% by 2050. Additionally, there have been calls within the industry to tighten or move up the timeline for these emissions targets.

Meanwhile, international progress toward lower CO2 emissions for the truckload and rail industries exist in pockets, despite these industries having higher carbon intensity per freight ton-mile. To date, an uptick in carbon emissions standards and costs for trucking and rail have mostly been limited to advanced economies, specifically in the Eurozone and Canada.

Note: The chart above models efficiency differences as the gross CO2 emissions. Actual emission differences across transportation modes may vary dramatically when revenue ton-miles are considered in analysis.

IMO 2020’s Tightening Standards May Lead to Tighter Budgets

IMO 2020 kicked off a decade with undeniable momentum toward a lower-emission future, and shippers should plan to budget accordingly. While it is true that change has a difficult time asserting itself against the establishment—particularly when it comes to emissions-saving fuel and technologies—there is reason to believe the near future will be different. At the heart of this argument is the traction of climate change in corporate and public policy initiatives.

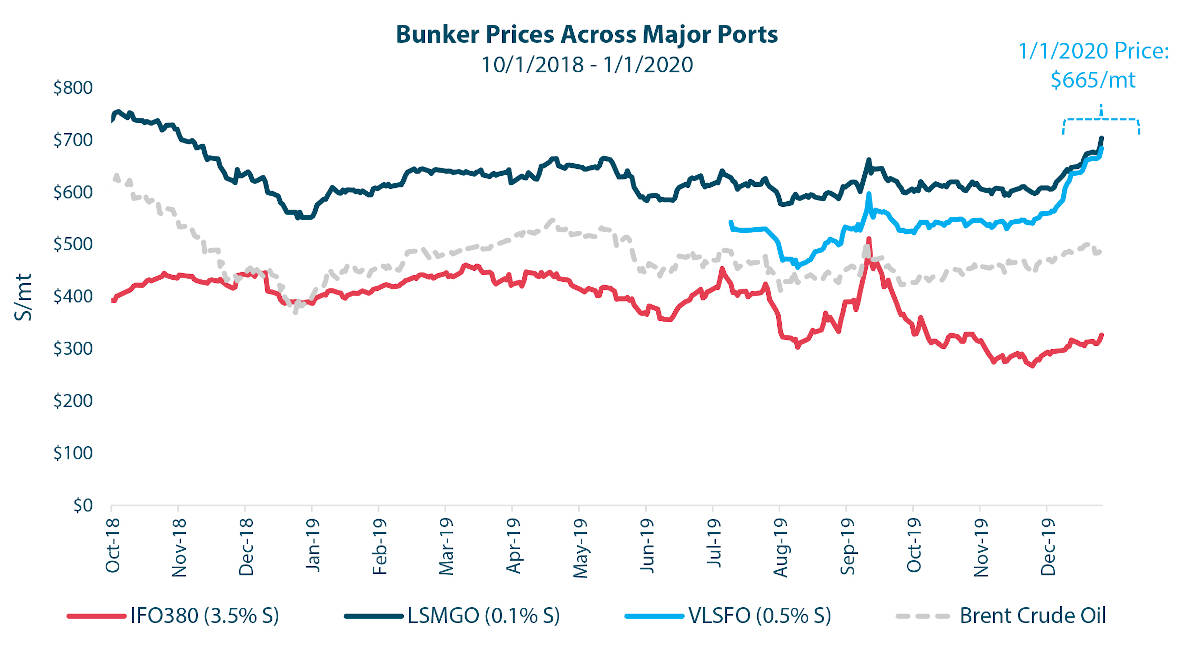

The past two years have helped shippers recall the risk associated with inadequate contingency plans to absorb the impact of policy shifts. The Trump administration’s abrupt shift in trade policy and the installation of tariffs were disruptive across supply chains, and potential shifts in emissions policy may not feel so different. The energy requirements of moving a heavy-duty truck can easily account for 20% to 30% of its operating costs, whereas fuel may account for over 50% of operating costs for moving containerized ocean freight. The significant impact of energy prices on transportation operating costs demonstrates the risk exposure users of these services will face should emissions regulations tighten.

IMO 2020 is an example of how cleaner emissions targets can potentially lead to higher transportation costs and disruptions to budgets. Not only is the conventional, high-sulfur marine fuel ceding much of its market share to low-sulfur fuels and emissions-reducing technologies, the increased low-sulfur fuel demand created by IMO 2020 has shifted international refining production and supply chains. All of this has culminated in a significant surge in marine fuel prices and ultimately more expensive maritime transportation costs for shippers moving goods to market.

How Should Shippers Navigate the Shifting Emissions Environment?

The IMO 2020 market transition demonstrated risks associated with tightening emissions policies that have not been widely addressed, and shippers think they have limited means to do so. This requires strategic navigation into the future.

First, shippers should be aware of their emissions exposure by mode of transportation and model the sensitivity of their network to changing emissions costs.

Secondly, shippers should determine where mode conversion develops earliest return-on-investment. As an example, how much of a carbon tax on diesel fuel merits converting truckload movements to intermodal moves? Where, geographically, does this make sense first?

Finally, shippers should implement strategies to lower the carbon intensity of the fuel consumed by their network. How might shifting part of a network toward compressed natural gas or biodiesel reach emissions reduction objectives and reduce future risk exposure?

Shippers must continually work toward reducing the cost, consumption, and emissions of moving their goods to market. Emissions will continue to increase their impact upon transportation networks as their full societal cost factors into the movement of freight. Shippers who advance their sustainability strategies ahead of policy change will create a competitive advantage.