One day early last week, as Brexit-era regulations first roared through, a Northern Irish hauler dispatched almost 300 goods-laden trucks to Britain. Normally, there would be an immediate turnaround, with trucks carrying goods destined to Northern Ireland, or onto Ireland. After two days, however, only 100 made it back fully loaded. The rest were stuck waiting for cargo, as British shippers and their agents unsuccessfully grappled with new paperwork and other customs-related issues. The truck operator ended up recalling his empty trucks, eating about $33,000 in the process.

The irony is that Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom. However, under the new UK-European Union pact, the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland remains free and unimpaired. Northern Ireland continues to be governed by EU standards. Goods moving into the territory from Britain must be EU certified and cleared.

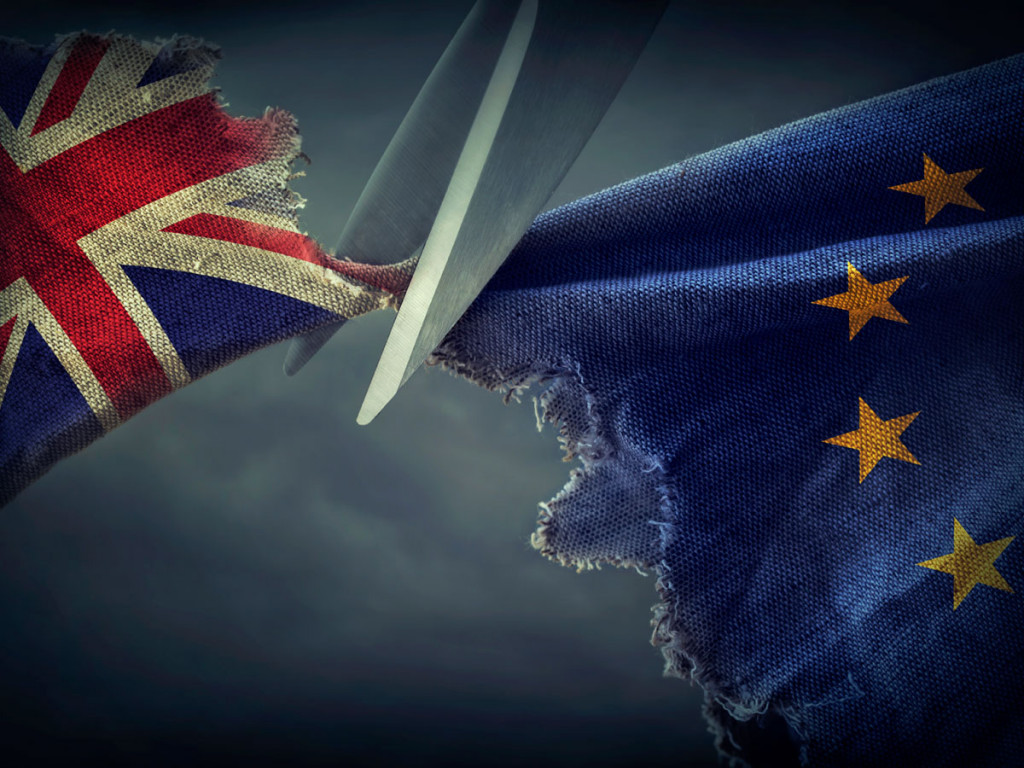

UK-EU Red Tape

While this could just be a case of early teething problems, logistics specialists and trade analysts fear it’s more likely a portent of the difficulties to come moving cargo to and from Britain.

“As we’re ramping up volume, things are not getting better,” said Duncan Buchanan, policy director at The Road Haulage Association, the trade association of logistics handlers in Britain and Northern Ireland. “We’re in the process of dealing with the most massive, complex changes imaginable. It’s actually simpler to send something to China than it is to send something to Germany now by road. We have a much more complicated supply chain system for Europe than we do for going anywhere else.”

“Economies try to get rid of red tape, but we’ve actually taken backward steps,” added Leheny.

Richard Greening, for DDC FPO, a global freight business process solutions company that offers specialized customs brokerage support for Brexit, commented, “The new regulations add to the complexity of process for these businesses, which has the potential to increase their time, resource needs and costs. It’s not just about ensuring compliance though; they need to find a way to manage this, whilst keeping their customers happy and ensuring the same service standards as pre-Brexit.”

“As we’re ramping up volume, things are not getting better,”

All this has happened, despite a last-minute trade deal between the UK and the EU that insures goods flow tariff-free between the two. As American Journal of Transportation has stressed before, free-trade doesn’t mean effortless trade.

“It’s not going to be frictionless,” said Aidan Flynn, general manager of the Freight Transport Association Ireland. “There are going to be delays because of all the new requirements.”

Flynn and others cited customs access and IT systems that were only tested in the hours before the new year because the agreement was finalized just days earlier.

“We should have had a deal two years ago and then we could have spent those two years on how to make this work better, not doing a deal on the 23rd of December. That’s absurd,” said Buchanan.

Brexit came into effect on January 1, but the realities of this new world order haven’t been tested as yet, and the signs aren’t good. During that initial week, the number of trucks crossing between Britain and the EU and Northern Ireland were down by anywhere from 40% to 75% over normal levels. Retailers and manufacturers alike had stockpiled goods throughout November and December, anticipating troubles in the new year and fearful that a free-trade agreement may not happen. Add to that Britain’s latest lockdown because of COVID-19, as well as large quantities of goods sitting in distribution centers because documents aren’t yet in order.

Even with the lower traffic, there has been fallout. Recently, DB Schenker, one of the world’s largest logistics companies, because of bureaucratic regulations announced that for the time being, it was not accepting new UK-bound consignments. Richard Bartlett, a Brexit trade advisor at Export Unlocked, aptly noted of the development, “DB Schenker may be ‘the canary in the coal mine’ for the logistics sector… If DB Schenker is struggling with incorrect or incomplete paperwork, what hope is there for small and medium sized logistics firms?”

When demand will again pick up is still a guess but reduced volumes can also be an opportunity. Greening observed, “As volumes initially look low, we should expect this to return to pre-Brexit levels fairly quickly and escalate as we better adapt to COVID-19. As with any new process, the first few weeks are a sharp learning curve, but soon become the norm.” Adding, that transport and logistics providers should use this time of reduced loads, for “proof of concept” and ensure that whatever decisions are made will stand up against growth and the impact of time-sensitive declarations, complexity and costs.

“As volumes initially look low, we should expect this to return to pre-Brexit levels fairly quickly and escalate as we better adapt to COVID-19.”

Under new rules, all shipments from Britain to the EU and vice-versa have to be pre-cleared. Rules of origin checks will be much stricter as well, as EU officials will now be on the lookout for third-country products and components used by British manufacturers.

That’s especially tricky for food and live plants and animals. French authorities have warned hauliers and logistics handlers that they will crack down beginning this week of paperwork for “sanitary and phytosanitary” regulated goods, primarily animals and animal products. According to French officials, trucks arriving from Britain have been almost totally non-compliant in terms of permits and paperwork. “They’re saying ‘it’s no more Mr. Nice Guy,’” said Buchanan. “‘You’re going to have to fill in everything properly, or we’re going to send bulk lorries back to the UK.’”

Problematic Preview of Future Trade

Britain experienced the perils of what would happen to trade in a no-deal environment in a devastatingly stark preview. The French, worried about the spread of a new strain of COVID-19, closed their ports to hauliers from Britain for two days beginning December 21. At least 1,500 British trucks were stranded along the M20 motorway leading to the port in Dover. Horrific scenes of desperate, hungry drivers stuck inside their trucks for hours blanketed the news.

“That gave everyone a bit of a reality check,” said Meredith Crowley, senior fellow at the think tank, The UK in a Changing Europe.

The British government itself had projected earlier last year that if there wasn’t a free-trade deal, as many as 7,000 trucks could be stuck outside Dover, waiting for customs clearance.

The two parties finalized a free-trade agreement on Christmas Eve, after the British government of Prime Minister Boris Johnson softened its stand and agreed to last-minute sticking points. Under the agreement, for example, the UK will be largely bound by EU rules regarding labor, environmental, climate, sustainability and “social” standards. The UK can’t impose subsidies or anti-anti-competitive practices that violate EU regulations.

To be sure, the trade deal should make cross-border movement of goods a bit easier, as well as cheaper. “There’s no financial consequences and therefore it should mean less customs checks and lorries checks, because obviously there’s no incentive there for anyone to evade tariffs,” Leheny believes.

Also, importantly, the deal maintains access for UK and EU trucks in each other’s territory. That’s crucial for cross-border trade as a no-deal would have required a highly restrictive permitting scheme that would have prohibited most cabotage operations. This could have crippled supply chains.

As it is, many supply chains will be stressed in the coming weeks and months. British analysts worry EU customers, concerned about the higher cost of doing business with the UK and the uncertainties of transport, will drop British suppliers. This will impact most seriously small and medium-sized enterprises, already weakened because of the COVID-19-led recession that has swept through the UK. “Some of those firms are going to go bankrupt during this collapse,” said Crowley.

These are businesses that are particularly ill-prepared for Brexit-era export regulations as well. That’s because they’ve had no reason to get involved in customs formalities, hire specialists or integrate reporting systems. Under EU law before Brexit, a British business exporting less than 250,000 pounds annually didn’t even have to report what goods were being sent, just the total export value each year.

Brexit, COVID-19 and the Economy

Just how bad Brexit will hurt the UK economy is complicated by COVID-19, which triggered Britain’s worst economic performance since the Great Depression. The British government in 2018 estimated that Brexit would cause a 5% GDP decline over ten years, a figure Crowley, for one, believes is still accurate.

The impact on the EU will be much less. According to the European Commission, the UK relied on the EU for “roughly half of its total trade in goods” in 2019, with the UK accounting for 13% of the EU’s total trade with third countries.

According to the European Commission, 230 million tons of cargo are transported between the EU and the UK, by air, sea, road and rail annually.

Northern Ireland-related transport and commerce become caught up in particularly complicated fashion under Brexit. To ensure continued free movement of people and goods between Ireland, an EU country, and Northern Ireland, part of the UK, Northern Ireland must abide by EU rules and regulations. That means an Irish Sea border check to ensure compliance of goods entering and leaving Northern Ireland.

While there’s a three-month transition period that lightens the requirements of supermarket-destined goods, Brexit has already caused disruption in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland as well.

Take, for example, the British supermarket chain Marks & Spencer. Because it couldn’t get goods delivered from Britain, it was forced to drop hundreds of items from its Northern Ireland stores and faced embarrassing images of empty shelves in its Dublin branches as well. “Tariff free does not feel like tariff free when you read the fine print,” the retailer’s chief executive, Steve Rowe, told ITV.

Northern Irish business hopes it can benefit from a post-Brexit realignment, becoming a manufacturing center for goods bound to the EU, while Irish logistics operators are weighing more direct shipments between Irish ports and the European continent. The loser in all this could be the so-called “land bridge,” in which goods have traveled from Ireland to Britain and then onto the EU and vice versa.

The free-trade agreement allows some further cooperation in the future. The European Commission itself cited as possible more streamlined procedures specifically for the ferries that transport the trucks across the English Channel. Crowley, for one, believes that will happen within the next year.

But in the meantime, everyone will have to adjust, and there will be pain. “The new reality of trading with Britain ensures that what went before will have to change,” concluded Flynn.

About the AJOT Breaking News sponsor

DDC FPO

As a strategic partner for the transportation industry, DDC FPO delivers business process solutions that enable clients to achieve their goals. To learn how DDC helped one Top 5 Global Logistics provider prepare for Brexit with 500 recruited, hired, and trained agents within 20 weeks - all while achieving 99% data accuracy click here.