A shortage of truckers across the U.S. has become so severe that companies are trying to bring in drivers from abroad like seemingly never before.

For the first time in her 10-year trucking career, Holly McCormick has found herself coordinating with an agency in South Africa to source foreign drivers. A recruiter for Groendyke Transport Inc., McCormick has doubled her budget since the pandemic and is still having trouble finding candidates.

As McCormick put it: “If we’re not able to haul these goods, our economy virtually shuts down.”

Trucking has emerged as one of the most acute bottlenecks in a supply chain that has all but unraveled amid the pandemic, worsening supply shortages across industries, further fanning inflation and threatening a broader economic recovery.

“We’re living through the worst driver shortage that we’ve seen in recent history, by far,” said Jose Gomez-Urquiza, the chief executive officer of Visa Solutions, an immigration agency with a focus on the transportation industry.

As a result, demand for Visa Solutions’ services from the trucking industry has more than doubled since before the pandemic, and “this is 100% because of the driver shortage,” he said.

Bringing in more foreign workers faces a number of hurdles including visa limits and complicated immigration rules, but trucking advocates see an opening now to overcome some of those obstacles after the Biden Administration created a task force to address the supply chain problems impeding the economic recovery.

In July, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, and Meera Joshi, deputy administrator of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, held a roundtable meeting with the trucking industry to discuss efforts to improve driver retention and reduce turnover. Among the measures the industry is seeking is lowering the minimum age to 18 from 21 for interstate drivers and adding trucking to the list of industries that can bypass some of the Department of Labor’s immigration certification process.

That would be a boon to Andre LeBlanc, vice president of operations at Petroleum Marketing Group, which oversees fuel delivery to around 1,300 gas stations, mostly in the northeast. Some of those depots have seen shortages for as many as 12 hours because “we simply can’t re-supply them because we don’t have the qualified drivers,” he said, estimating the group needs about 40 more to run at full capacity. Meanwhile, of the 24 drivers LeBlanc has tried to hire through a federal immigration program, only three have gotten through all steps of the verification process.

“We’ve got 21 drivers right now who are qualified, who can come to this country the right way and are ready to come here and solve this problem,” he said. “We can’t seem to get an answer on what we need to do to move that forward.”

On top of the pandemic early retirements, last year’s lockdowns also made it harder for new drivers to access commercial-trucking schools and get licensed. Companies have offered higher wages, signing bonuses and increased benefits. So far, their efforts haven’t done enough to attract domestic workers to an industry with grueling hours, a difficult life-work balance and an entrenched boom-bust cycle.

In 2019, the U.S. was already short 60,000 drivers, according to the American Trucking Associations. That number is anticipated to swell to 100,000 by 2023, according to Bob Costello, the group’s chief economist.

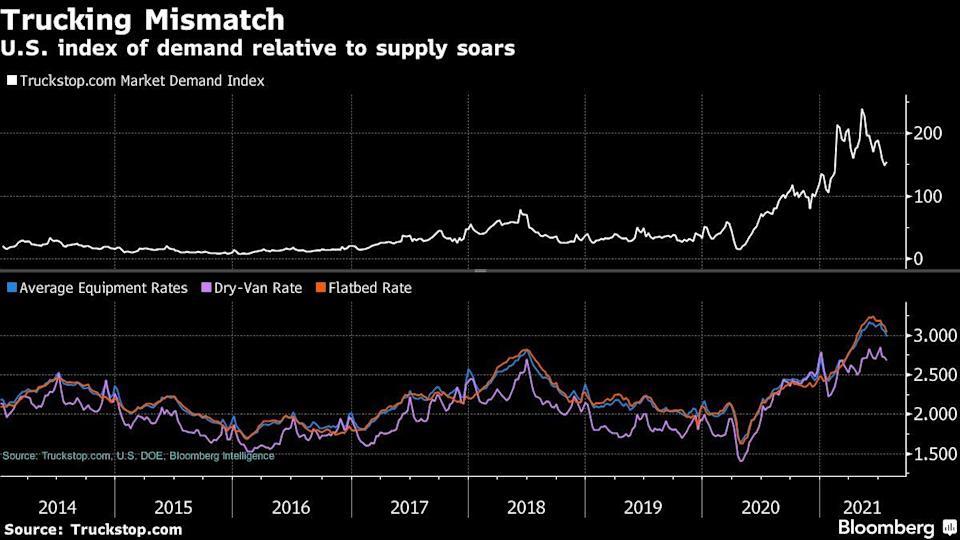

For an indication of just how acute the mismatch between supply and demand is, check out Truckstop.com’s Market Demand Index. While the measure has cooled a bit since reaching an all-time high in May, it’s up more than fourfold from this time in 2019.

Spot Trucking Market Should Stay Tighter Than Historical Norms

That underscores why companies are increasingly turning to drivers from South Africa and Canada, according to Craig Fuller, the founder and CEO of the data and information firm Freightwaves. Workers from those countries can often speak English, making it easier to get the necessary license.

Still, Fuller points out that simply bringing in more foreign labor won’t solve all the issues creating snarls in the industry. There’s also a capacity shortage, or an unusually small number of trucks on the road, at the same time that demand has surged, he said.

“Even if there were drivers, there is a finite number of trucks at any moment in time, so you have two issues happening,” Fuller said.

In the meantime, Andrew Owens, the CEO of A&M Transport, is looking to address his driver shortage with immigrant labor from Mexico, Europe, South Africa and Canada. The delivery company has brought in 20 foreign workers in the last year, but Owens would ideally like to hire at least a dozen more to meet demand needs. He’s been waiting on approvals since 2017 for a contract with 15 workers, only two of whom are now through the process that he was first told would take about 13 to 18 months.

“They all have verifiable truck driving experience,” Owens said. “The only thing we need to do is teach them to drive on the right side of the road, and they’re good to go.”

_Alliance_-_127500_-_b8933d3fb84a2acdb9eadbb9044f8ff29c748df0_yes.png)

_Alliance_-_127500_-_8518a8cb53bfa1ee3241a9389b0c47f7b53ad9ce_lqip.png)