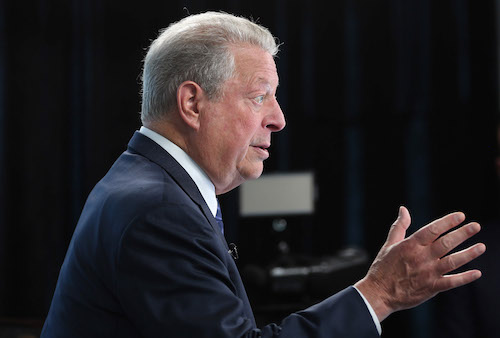

A global coalition co-founded by Al Gore, the former US vice president, has released a granular database tracking global greenhouse gas emissions, down to the individual polluter. And some of the world’s biggest companies are planning to use this data to decarbonize their supply chains.

Climate TRACE uses machine learning, satellites and other technology to detect and track greenhouse gas emissions. That information is then bundled up into a public inventory, the latest of which was announced this weekend by Gore at the COP28 climate talks in Dubai. The database covers more than 350 million sources of greenhouse gas pollution such as individual power plants, steel mills and mining operations. That level of specificity allows companies to build a low-emissions supply chain rather than relying on suppliers’ self-reported emissions data, said Gavin McCormick, co-founding member of the coalition.

Companies that have newly signed on to use Climate TRACE’s data to gather more information on steel and aluminum supplier emissions include Tesla, Boeing and General Motors. Some companies using the inventory have already told McCormick they're finding cleaner manufacturing facilities that offer similar prices to their current suppliers and have the capacity to handle new customers, though he didn’t name them specifically.

Working with companies on steel and aluminum supplier emissions is just an initial “proof of concept,” McCormick said. The coalition — which includes data scientists, AI researchers and nongovernmental organizations — plans to expand its partnerships next year to include exploring emissions reduction potential within lumber, rice, cement and beef suppliers. Climate TRACE also has designs to include air pollution in its inventory and publish inventories at a monthly or even weekly place. While the group doesn’t want to be “the climate police,” McCormick said it’s open to working with governments interested in levying tariffs to goods from polluting facilities.

Machine learning models can process massive amounts of emissions data, but they also risk missing extreme sources of emissions, or “infrequent but very consequential events” like methane plumes, according to Mallory Barnes, an assistant professor at Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs and a member of NASA’s Carbon Monitoring System.

To help account for those outliers, Climate TRACE provides confidence and uncertainty estimates for every asset in its database, McCormick said. Sectors in which those infrequent events are a large percentage of their emissions receive high uncertainty and low confidence ratings.

Beyond detailing individual facility emissions, this inventory release — Climate TRACE’s third since it launched in 2020 — also reveals larger country-level insights. One of the most damning: The host country of this year’s climate conference, the United Arab Emirates, may have underestimated its own emissions by over 100 million tons, a discrepancy which McCormick partly ascribes to underreporting by the oil and gas sector. The country’s latest 2019 numbers were 225 million tons, while Climate TRACE put the figure at over 350 million tons. (Both figures excluding aviation and maritime shipping, which the UNFCCC doesn’t require countries to include in national totals.)

“They have no explanation for the discrepancy,” Gore said. “A stocktake has to be a truthful stocktake, and they have simply ignored lots of emissions that we can measure and report.”

Moreover, the UAE’s figure is growing: The coalition puts the country’s emissions today at close to 400 million tons.

“What [it] looks like is going on is that a lot of countries are kind of measuring the stuff they know about and assuming the rest is zero,” McCormick said, noting that’s simply not the case.