The Biden administration is set to unveil tight restrictions on new operations in China by semiconductor manufacturers that get federal funds to build in the US.

The $50 billion CHIPS and Science Act will bar firms that win grants from expanding output by 5% for advanced chips and 10% for older technology, according to officials at the Commerce Department, which will disburse the funds.

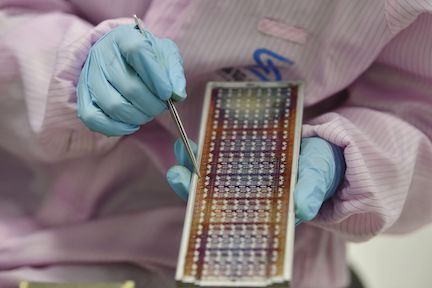

Those so-called guardrails are part of Washington’s efforts to thwart Beijing’s ambitions while securing supply of the components that underpin revolutionary technologies, including AI and supercomputers, as well as everyday electronics. In past years, the US has blacklisted Chinese technology champions, sought to cut off the flow of sophisticated processors and banned its citizens from providing certain help to China’s chip industry.

The new restrictions tied to the CHIPS Act aim to impose more onerous limitations on companies expected to secure incentives, including industry leaders Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Samsung Electronics Co. and Intel Corp., which all operate in China. The restrictions could hamper longer-term efforts to chase growth in the world’s largest semiconductor market, while also making it hard for Beijing to build up cutting-edge capabilities at home.

“CHIPS for America is fundamentally a national security initiative and these guardrails will help ensure malign actors do not have access to the cutting-edge technology that can be used against America and our allies,” Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo is expected to say in a statement, which was seen by Bloomberg News. “We will also continue coordinating with our allies and partners to ensure this program advances our shared goals, strengthens global supply chains, and enhances our collective security.”

To ensure federal funding beneficiaries cannot meaningfully expand advanced production capacity in what the law terms “countries of concern,” which includes China and Russia, the new rules will ban those firms from spending more than $100,000 when adding capacity for logic chips more sophisticated than 28-nanometers. They also cannot add more than 5% to the existing capacity of any single plant making these semiconductors in China.

While the proposed rule limits manufacturing expansion, grant recipients can still make technology upgrades to existing facilities to produce more-advanced semiconductors, if the companies receive any necessary export control licenses from the Commerce Department for doing so, an official familiar with the rule said. For example, a recipient upgrading the technological capability of a facility can include making logic chips at a smaller node size or memory chips with more layers.

Typically, a smaller number in nanometers indicates a more advanced generation for logic chips, which process information or handle tasks. Limits on the advanced capacity investments will be in place for 10 years.

A single advanced chipmaking machine from a supplier like ASML Holding NV, Applied Materials Inc. or Tokyo Electron Ltd. can cost tens of millions of dollars.

Grant recipients also aren’t allowed to increase capacity by more than 10% at their existing facilities in “countries of concern” for logic chips that are 28-nanometers or less-advanced, which the law defines as legacy semiconductors. If they want to build new factories for this type of chip, at least 85% of the output must be consumed by the host country and the companies must notify the Commerce Department.

While 28-nanometer chips are several generations behind the most cutting-edge semiconductors available, they’re used in a wide range of products including cars and smartphones. The US can claw back the full amount of federal grants if a recipient violates the rules, Commerce has said.

The new restrictions will make it even more challenging for TSMC to upgrade or expand its most-advanced Chinese plant in the eastern city of Nanjing, where it’s manufacturing 28-nanometer and more-advanced 16-nanometer chips. In October, Chief Executive Officer C. C. Wei said TSMC was granted a one-year license from the US government to grow production in China, temporarily exempting it from sweeping export control measures rolled out that month.

Memory chipmakers such as Samsung will see tighter restrictions on their expansions in China as Commerce will align the new guardrails with prohibited technology thresholds released in October. The South Korean company runs a major site in the central city of Xi’an making NAND flash memory. Intel has a chip-packaging facility in the central city of Chengdu, a modest operation compared to the others.

Federal grant recipients will also be prohibited from engaging in joint research with, or licensing technology to, a foreign entity of concern. That will cover any research and development done by two or more people. Licensing will be defined as an agreement to make patents, trade secrets or knowhow available to another party.

The list of foreign entities of concern will be broadened to include names on the Commerce Department’s entity list, the Treasury Department’s list of Chinese military companies, and the Federal Communications Commission’s list of equipment and services posing national security risks. That encompasses a host of China’s largest tech companies including Huawei Technologies Co., AI giant SenseTime Group Inc. and chip leaders such as Yangtze Memory Technologies Co.

The proposed rules will allow for 60 days of public comment before finalized regulations are published later this year.