Sustained efforts by the US to boost domestic solar PV manufacturing capabilities by imposing anti-dumping tariffs on Chinese modules have comprehensively failed, a Rystad Energy report reveals. Although the tariffs have indeed decimated direct shipments from China, they have been unsuccessful in decreasing overall US dependency on imports, which are set to hit a new annual record in 2021.

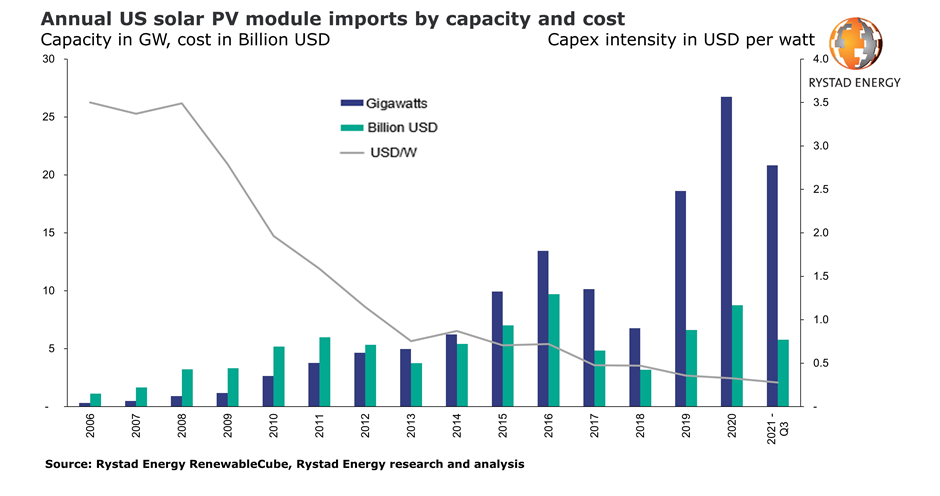

The US is on track to import a record 27.8 gigawatts (GW) of solar PV panels in 2021 from a range of countries, up from 26.7 GW last year. If recent import trends continue, solar PV imports for 2021 will be worth $8.9 billion in total, a marginal increase from the 2020 total of $8.7 billion, which was also a new record at the time.

However, the goal of stimulating domestic manufacturing capabilities was not achieved, as the US instead filled its supply vacuum with panels from other Asian countries. In 2021, US-manufactured solar PV modules are projected to total 5.2 GW, compared with the 27.8 GW expected from imports. Of this 5.2 GW, around half will come from thin-film panel manufacturing, primarily by First Solar, the world leader in thin-film production. The other half is the more widely used imported composite silicon (cSi) panels, although the projected 2.5 GW represents a mere 50% of total US manufacturing capacity.

Diving deeper into the origin of US solar PV imports, Malaysia became the market leader in 2020, capturing 42% of the US import market share, followed by Vietnam with 38%. In 2021 to date, these countries account for 31% and 28.8% respectively, with Thailand in third place at 26.2%. The decrease in market share for Malaysia and Vietnam illustrates a rise in imports from other nations, including Thailand and South Korea. Only 1% of 2021 year-to-date imports come from regions outside of Asia.

As the solar industry in the US has grown in recent years, the government has strived to protect its domestic solar PV manufacturing capacity, primarily through imposing tariffs on Chinese imports. However, these punitive policies are doing little to boost domestic production. Instead, they are pushing the cost of panels higher and shifting their country of origin to other Asian nations.

“The US tariffs are doing little to boost domestic production. Instead, they are pushing the cost of panels higher and shifting their country of origin to other countries in Asia. Policymakers should reconsider their strategies for the US to rise in the global PV manufacturing market and supply domestic demand. A way forward could be emulating the tax credit schemes that have been instrumental in solar and wind capacity deployments in the country,” says Marcelo Ortega, renewables analyst with Rystad Energy.

Although these imported modules originate from Southeast Asia, the manufacturers are typically Chinese enterprises that have offshored the assembly phase, the last step in PV module production. Some efforts to counteract these strategies by Chinese companies have been proposed by the US but have so far fallen short.

In 2018, the Trump administration doubled down on attempts to foster a domestic supply chain for solar PV panels, enacting Section 201 tariffs on imported cSi. The policy heavily impacted PV imports and capacity installations in 2018, lowering imports to 6.8 GW, down 66.7% from the 10.2 GW imported in 2017. However, the industry bounced back in 2019 and 2020 thanks in part to a temporary tariff exemption and the scheduled phasing down of tariffs.

In August 2021, the US Department of Commerce received an anonymous petition to investigate Chinese manufacturers circumventing anti-dumping tariffs by relocating facilities to Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. The move could have expanded the tariffs to include these countries but the request was rejected in November. If passed, the impact on US manufacturing would likely have been negligible.

In 2015, a similar investigation into Taiwan-manufactured PV modules led to a tariff extension covering Taiwan and effectively killed its panel exports to the US. However, instead of US manufacturing stepping up, facilities were moved to elsewhere in Asia, such as Malaysia. Extending anti-dumping tariffs to other nations does not seem to incentivize US domestic manufacturing.

Despite the US’ cSi PV module manufacturing capacity of 5.5 GW per year, this capacity is exclusively module assembly and relies on imported PV cells produced overseas. Asia is the PV cell market leader, with 52% of US imports of solar cells so far this year coming from South Korea, 25% from Malaysia and 15% from Thailand. The US is set to import a record volume of PV cells in 2021, with 3 GW expected by the end of the year, eclipsing the 2.5 GW imported in 2019.

This suggests that while US domestic module assembly capabilities are ramping up, current import levels indicate a meager 50.8% manufacturing capacity utilization rate without accounting for any domestic PV cell production.

The US benefits from some domestic polysilicon production, but after the 2012 tariffs imposed on Chinese panels, China retaliated with duties on solar-grade polysilicon imported from the US, thereby propping up Chinese domestic production and setting the scene for it to become the world’s largest supplier. China now holds 97% and 79% of all silicon wafer and cell production, respectively, which indicates that practically no US-produced silicon makes it back into a PV cell or module.

“Without meaningful change, the US solar industry is at risk of becoming assembly-only, continuing its reliance on overseas commodities for the early stages of the supply chain in order to ramp up solar capacity to meet demand,” Ortega concludes.