China’s trade surplus is set to top a record $1 trillion this year, but that won’t be enough to prevent the yuan from sliding against the surging dollar as business confidence wanes, according Macquarie Group Ltd.

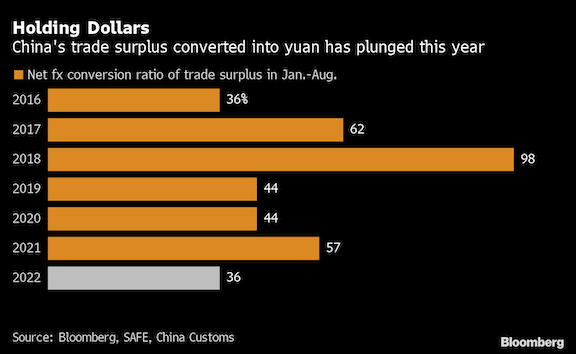

While China’s goods surplus is on track to reach the highest ever in world history, exporters have been reluctant to convert their foreign exchange back into yuan given the plunge in business sentiment this year, Macquarie’s chief China economist Larry Hu wrote in a note.

Exporters may be betting on a further slide in the currency amid a weaker economy, or have felt lesser need to convert their foreign proceeds into local currency as there is lower demand to re-invest in their operations in yuan-denominated working capital, according to Macquarie. That means the goods surplus has played a lesser role in buffering the yuan’s decline.

“Despite the record high trade surplus, the yuan is under strong depreciation pressure against the US dollar,” said Hu. Given the dollar’s strength and weak business confidence, Macquarie’s currency strategists expect the yuan to slide to 7.15 against the greenback by the end of this year, he wrote in the report, which was published before the yuan surpassed that level on Monday.

The conversion rate of goods trade could be the “game changer” for the currency, Hu said. If it hadn’t dropped as much in the second quarter, the surging goods trade surplus this year would have been able to offset the outflows from other sources, like the bond market, he said.

Hence, China may need more, not less, policy easing in order to stabilize the yuan, Hu argues -- contrary to conventional expectations that more easing could weaken the currency.

“If a strong economic recovery leads to higher confidence, exporters would then convert more dollar into the yuan,” according to Hu.

China has seen its good trade surplus swell since the pandemic thanks in part to its Covid Zero policies, which have preserved supply capacity for exports while suppressing internal demand and imports. Domestic consumption has also been weakened by its ongoing property crisis and a reluctance by regulators to flood the economy with liquidity, instead electing for targeted support and industrial policies and fiscal spending to spur growth.

However, China’s export growth could be losing steam as surging inflation across the globe and an energy crisis weakens global demand. Exports last month rose at the slowest pace since April when the Shanghai lockdown disrupted shipping.