The aviation industry is under pressure to do something about the immense amount of carbon emissions its engines generate. The output is accelerating many times faster than from sectors such as energy and agriculture, contributing to global warming.

Paul Eremenko, a 41-old former chief technology officer for Airbus SE and United Technologies Corp., thinks he has a solution: hydrogen-powered airplanes. He well understands, of course, that his idea has a bit of a public relations problem right from the start. Hydrogen power and flight conjures up visions of the flaming Hindenburg airship.

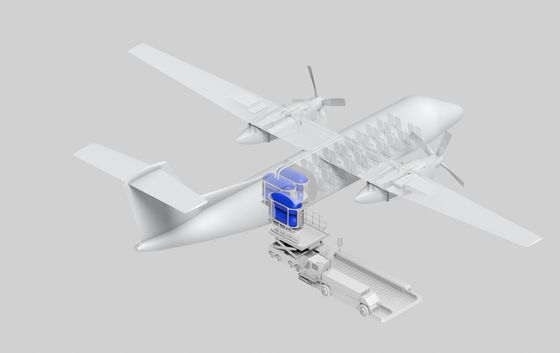

So Eremenko’s startup, called Universal Hydrogen Co., has developed Kevlar-coated, pill-shaped pods — about 7 feet in length and 3 in diameter — filled with hydrogen. The pods are designed to double as a storage container for transporting the hydrogen, by truck, train or other means, and a gas tank when loaded into a plane. If filled with water, each would hold about 208 gallons, and they can be stacked in racks so that 54 would fit inside a standard freight shipping container. They can even be loaded into a plane with a forklift, he said. The point is that airports wouldn’t need pipelines or underground tanks.

``We want to basically turn hydrogen into dry freight,’’ said Eremenko.

Universal Hydrogen has no interest in becoming an aircraft maker itself. Instead, starting in 2024, the company plans to offer not just the pods but a retrofit kit for converting a 50-seat, single-aisle, regional aircraft to run on fuel cells (although making room for the capsules would mean the planes would only have 40 seats after the switch). The converted planes would exist largely to show the industry how to make this future work. He wants the planes in the air before Boeing Co. and Airbus decide on designs for replacing their own single-aisle planes, expected to happen in the next decade. Although Universal Hydrogen will focus on planes with hydrogen fuel cells, the same pods could also one day be used to power planes that burn hydrogen in jet engines.

``There is fundamentally an incrementalist mindset in the incumbents,’’ Eremenko said. ``Hydrogen is a fairly drastic step for the industry. I think it’s a necessary step, given the industry has no other way to meet the goals of the Paris agreement.’’

Air travel accounts for roughly 2.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and before the pandemic at least, it was steadily growing. While some engineers are developing small electrified aircraft, current batteries are too heavy to power commercial planes on their own. Airlines have run highly publicized flights on biofuel blends, but Eremenko considers biofuels a stopgap measure, even if they achieve mass production.

``You’re still burning hydrocarbons at altitude, with soot and aerosols,’’ he said. Provided the hydrogen is generated from water by electrolysis using renewable power, it can be carbon-free. “Flight shaming” – the avoidance of airline travel due to its carbon footprint and the shaming of people who fly – would become a thing of the past.

Hydrogen has its own challenges to overcome in the air, of course. Ever since the Hindenburg burst into flames while docking in 1937, part of the public has viewed hydrogen warily. But its proponents, including companies that have explored hydrogen for powering cars as well as airplanes, consider that fear overblown. As countless plane and car crashes have shown, conventional fuels can be quite explosive on their own. And because it is so light, hydrogen rises when accidentally released, rather than pooling as jet fuel does. Eremenko considers it safer than jet fuel and believes the public, growing used to hydrogen-powered buses and cars that are already on the road, will get over its aversion.

Tom Enders, a former Airbus chief executive officer who is advising the startup, said the main market would be for medium-range, single-aisle aircraft. And while such planes are less commonly used in the United States, they constitute the vast majority of aircraft worldwide, he said via email. ``In other words, there is a huge market potential.’’

Eremenko formed the startup with other aviation veterans after leaving United Technologies last year. The business has so far been self-funded, with about $3 million from its core team and $5 million from partners. To reach production, he estimated Universal Hydrogen will need to raise about $300 million.

The same hydrogen storage solution, if successful in aviation, could one day be used in other industries, he said. Cargo ship builders are also exploring fuel cells as a future power source. But Eremenko prefers to start with planes.

``Ultimately, we think aviation is the killer app, because aviation doesn’t have an alternative,’’ he said. ``Also, it’s fun for us, because we’re aviation people.’’