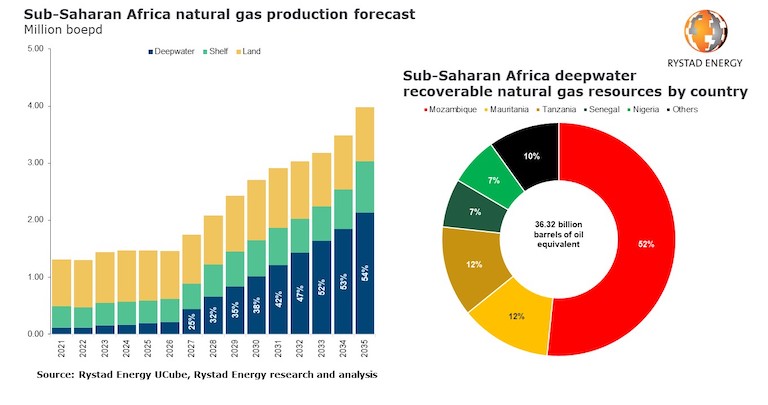

Untapped natural gas supplies in Sub-Saharan Africa are set to be unleashed this decade, with output more than doubling from 1.3 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (boepd) in 2021 to 2.7 million boepd in 2030 due to vast undeveloped deepwater resources, Rystad Energy research shows.

While deepwater developments have played a crucial role in the region’s liquids output to date, averaging about 50% of annual production, gas output from such fields has been minimal. That is expected to change, however, as gas from deepwater reserves will surge in the coming years. Production from deepwater developments will skyrocket from 120,000 boepd in 2021, 9% of total output including shelf and land production, to 1 million boepd accounting for 38% of total output.

As a result of the booming production outlook, greenfield investments are also projected to soar. Gas and liquids greenfield capital expenditure in the region totaled $12 billion in 2021, with $8 billion spent on deepwater developments. By 2030, total greenfield investments will surge to almost $40 billion, of which $24 billion will go on deepwater projects.

“Production in Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to increase significantly in the coming years, with natural gas output in particular set to see a boom in output. Although there have been notable onshore finds, the development of deepwater offshore resources is going to usher in a period of rapid growth for the region,” says Siva Prasad, senior upstream analyst with Rystad Energy.

Natural gas production in Sub-Saharan Africa has been historically low, but that looks set to change due to significant undeveloped deepwater finds in countries including Mozambique, South Africa and Mauritania. Deepwater reservoirs tagged to TotalEnergies’ Area 4 LNG project in Mozambique, where trains 1 and 2 are expected to start production in 2028, hold an estimated 2.3 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe) in gas reserves. South Africa’s Brulpadda field – also operated by the French major – holds 715 million boe, while the BP-operated Greater Tortue Ahmeyim floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) development straddling the maritime boundary of Mauritania and Senegal has an estimated 300 million boe.

Of the current potential recoverable reserves across Sub-Saharan Africa, about 60% lie in deepwater regions, of which close to 60% is gas. Mozambique dominates with 52% of the total recoverable gas resources in the area, followed by the Senegal–Mauritania maritime region with a combined 20% and Tanzania with about 12%. Nigeria also holds significant recoverable reserves of gas that will contribute to the expected output hike.

On the flip side, Sub-Saharan African liquids production is expected to drop below 4 million barrels per day (bpd) for the first time in more than 20 years but will recover by 2028 and return to 2020 levels of around 4.4 million bpd by the end of the decade. Liquids output is projected to grow in the 2030s, too, with total production of approximately 5 million bpd in 2035.

About 40% of the total recoverable deepwater resources in the region are liquids, of which Nigeria accounts for 33% and Angola has 31%. Ghana and Mozambique are two other countries with significant untapped resources, amounting to 8% and 7%, respectively, of the region’s deepwater liquids reserves.

Deepwater projects in Sub-Saharan Africa are, however, risky and can be delayed or unsanctioned due to high development costs, challenges accessing financing, issues with fiscal regimes and other above-ground risks. With majors continuing to rein in upstream spending and plow a course on the energy transition to help lower emissions, many deepwater schemes will face challenges getting off the drawing board.

Majors are, overall, focused on cutting upstream costs, reducing emissions, increasing renewables and the energy transition, meaning such deepwater projects often have to take a backseat when it comes to apportioning investment. European banks are tightening regulations for funding high-emission hydrocarbon projects, and African banks could struggle to provide the necessary financing. This leaves Asian banks – mainly Chinese – with comparatively less strict regulations on funding fossil fuel developments.