Global oil production is slowly recovering towards pre-Covid-19 levels, but in West Africa the pandemic is set to leave lasting effects. This important region for sweet crude oil production faces numerous challenges as it strives to heal from the pandemic, including underinvestment, a lack of infill drilling at mature fields, and infrastructure that is either ageing or threatened, a Rystad Energy analysis showed.

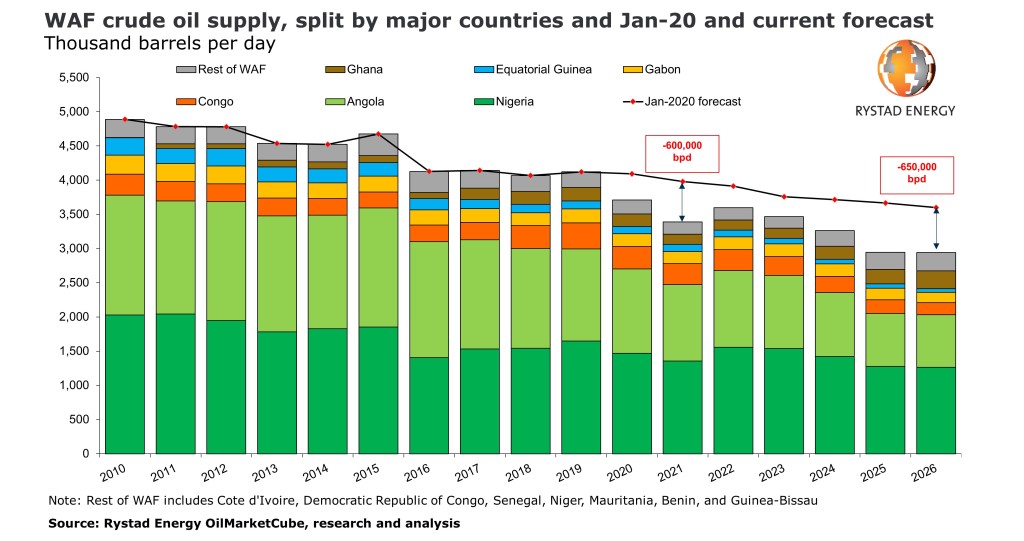

Sweet crude is the preferred oil grade to make jet fuel – the worst-hit segment as oil demand plunged last year. West African crude oil production dropped to 3.71 million barrels per day (bpd) last year from 4.12 million bpd in 2019, and is set to decline further to 3.39 million bpd this year. While we expect output to tick back up in 2022 and 2023 as jet fuel demand returns, production is set to fall below 3 million bpd already from 2025 unless heavyweights Nigeria and Angola can stage a strong comeback and shake off the dismal growth trends of the past decade.

As a result, Rystad Energy has reduced its forecast for West African crude oil output by 600,000 bpd for 2021 and by 650,000 bpd for 2026, compared with our pre-Covid-19 projections.

“The structural upstream obstacles that West Africa faces are realities that are not going away in the short term. Even if jet fuel makes a spectacular recovery and demand for light and medium sweet crude grades returns, Nigeria and Angola, as well as other neighbors in structural upstream decline, will not be in a position to supply the market,” says Nishant Bhushan, upstream analyst at Rystad Energy.

The region’s decline in 2021 is driven by its two biggest oil producers, Nigeria and Angola, which together are estimated to have lost 440,000 bpd versus the pre-Covid-19 forecast. We also estimate that crude oil production has dropped significantly in countries such as Congo, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, which together produced between 250,000 bpd and 300,000 bpd in 2010. Equatorial Guinea has seen a 60% reduction in oil production and Gabon nearly 35% in the past 11 years.

Crude oil production from West African countries was expected to pick up pace in tandem with their Middle Eastern counterparts as the OPEC+ group opened its supply taps. But even as OPEC+ production caps have gradually eased, Nigeria and Angola have not been able to ramp back up to their pre-shut-in production levels.

Crude production is not the only thing that’s been hit in the past couple of years. Since the start of 2020, we have also seen that the overall crude production capacity in Nigeria and Angola has taken a major blow. This is due to a number of reasons, including rapid declines at mature fields due to a lack of infill drilling, postponement of final investment decisions that were originally planned for 2020 and 2021, a lack of investment in oil and pipeline infrastructure which leads to frequent production shut-ins (prevalent in Nigeria), and civil unrest caused by militia groups.

West Africa has never had much unused capacity – most countries have produced at maximum capacity even as that capacity was gradually declining. When OPEC+ unveiled its massive 9.8 million bpd cut program in May 2020, the region had an overall oil production capacity of 4.2 million bpd. We estimate this has dropped by almost 420,000 bpd to around 3.8 million bpd by the end of 2021, and will keep shrinking to 3.5-3.6 million bpd by the end of next year.

Nigeria

Nigeria produces sweet crude grades ranging from light to heavy, but most of the volumes fall into medium to light grades. We expect the output of all sweet crude grades in Nigeria will decrease on the back of declining production from mature fields. The major drop in crude oil production is in grades like Bonga, Egina, and Qua IBoe, which are estimated to fall collectively by 180,000 bpd to 200,000 bpd by 2026 from 2021. Other crude grades, like Forcados, Bonny Light, Escravos, and Erha, are estimated to remain little changed, while some growth will be seen in crude grades like Amenam, Brass River, and Jonas Creek.

The decline in Nigeria’s crude oil production in recent years looks more structural as the country has failed to attract new investments in its oil and gas industry, be it in exploration, greenfield developments, or brownfield expansions. In the short term, we estimate Nigeria’s crude oil production will rise to about 1.55 million bpd in 2022 and 1.58 million bpd in 2023, with some new marginal field developments adding 30,000-35,000 bpd in 2022 and another 35,000-40,000 bpd in 2023. At the same time, some fields currently in the ramp-up phase are estimated to add 65,000-70,000 bpd in 2022, but only 10,000-15,000 bpd in 2023. After 2023, we estimate Nigeria's output will continue to slide due to a lack of significant new discoveries, slipping to as low as 1.25 million bpd by 2026.

Angola

Like Nigeria, Angola’s decline in crude oil production is also structural, and production has been plummeting since 2015 – from 1.74 million bpd in 2015 to almost 1.11 million bpd in 2021. This output slump is the direct result of a lack of new investments in exploration and a failure by operators to halt the production decline at mature oil fields. New upstream projects are estimated to add 40,000-45,000 bpd this year and another 80,000-90,000 bpd in 2022, but this will not be enough to halt the downward spiral that will reduce Angola’s crude oil production to between 750,000 bpd and 800,000 bpd by 2026.

Angola mostly produces sweet crude, and we expect production of all the major sweet crude grades to slide in the coming years. We see overall sweet to regular crude grade output slumping by almost 300,000 bpd from 2021 to 2026 – a drop of about 30%. Major crude grades such as Nemba, Dalia, Mostarda, Gindungo, Girassol, and Kissanje are estimated to cumulatively decline by 280,000-300,000 bpd in 2026 from 2021. Some smaller crude grades like Sangos, Saturno, Cabinda, and Plutonio are estimated to remain at similar levels or inch up by 15,000-20,000 bpd combined.