Last month, 13 copper-industry representatives at the London Metal Exchange were asked whether Russian metal should be blocked from its warehouses. Ten of them said “yes.” But when advisory groups for nickel and aluminum discussed the same question, the general consensus was “no.”

The LME, which is the ultimate decision-maker, says it won’t take action that goes beyond government sanctions—which, so far, have left most of the metals industry untouched.

For now, Russian metal is largely still flowing to the world’s factories and building sites. Many traders and fabricators who buy from Russian companies are tied in to pre-existing purchase deals that can extend over years. And commodities merchants have a well-earned reputation as buyers and financiers of last resort when others have long backed away.

Still, a growing number in the industry say they won’t take on new Russian business, and some are actively working to disentangle themselves. That’s making it ever-harder for Russia’s metals producers to sell whatever output is not already contracted, and may ultimately force them to cut production if there’s no change by the time long-term deals come to an end.

For the LME, the risk is that material mined in Russia starts piling up in its warehouses because it has nowhere else to go, creating dangerous dislocations at the nexus of the global metals trade.

“We see from our customer base there is hardly any interest to buy Russian metal if they can avoid it—and they can,” said Roland Harings, chief executive officer of copper giant Aurubis AG, which is represented on the LME copper committee. If the metal flows to the LME instead, “then you have this phantom stock which has an influence on the market because it shows high stock levels but nobody wants it.”

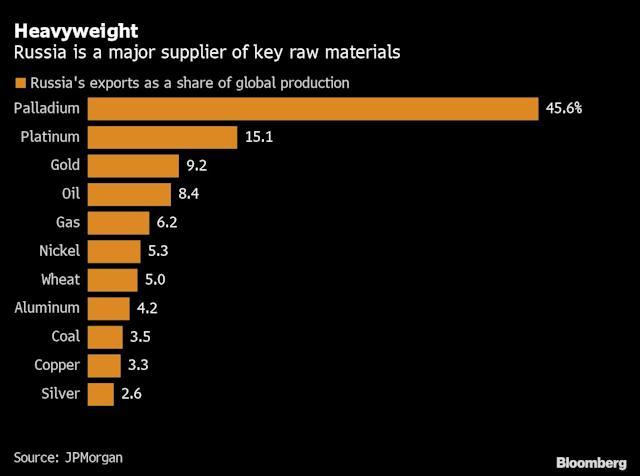

The question of what happens to Russia’s metal exports is of vast consequence to global markets—it’s a key supplier of palladium, nickel, aluminum, steel and copper. Prices for all of those metals set new all-time highs in March, although steel is the only one to be the direct target of sanctions so far.

Aurubis, Europe’s largest copper smelter, is “trying to get out” of its contracts for Russian supplies, and is in favor of sanctions against metals, Harings said in an interview last week. “I believe in the end whatever money we pay will end up in the wrong pockets,” he said.

Norwegian aluminum company Norsk Hydro ASA said it was taking the minimum possible under its contracts with Russian companies and was aiming to reduce that further.

There are still buyers for now—even in Europe. Russian metals producers like MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC and United Co. Rusal International PJSC tend to sell on annual or multi-annual deals to big industrial groups, and for the most part these contracts are still being fulfilled, according to people familiar with the matter.

Traders like Glencore Plc, which has a deal to buy aluminum from Rusal until at least 2024, and Trafigura Group, which has a long-standing relationship with Nornickel, are also fulfilling contracts in Russia.

Still, there are big challenges. Most container shipping lines have stopped calling at Russian ports. Precious metals like gold and palladium are typically sent to Switzerland or London by plane—but most flights out of Russia are now grounded.

And few new deals are happening. Glencore, which has been one of the largest traders of Russian commodities since the days when founder Marc Rich struck agreements with the Soviet Union, announced last week it would do no new business in Russia.

Traders say it’s nearly impossible to find banks willing to finance new purchases of Russian metals, even in China, the world’s biggest metals consumer.

That’s where the debate over the LME comes in.

Producers generally prefer to sell their metal to end users, but delivering onto the exchange is also an option. Buyers on the LME don’t know whose metal they will receive until the contracts expire.

Those arguing for a ban on Russian metal say there’s a risk that the country’s producers could dump large volumes of metal into LME warehouses to raise cash quickly. If it became clear that LME stocks were dominated by Russian metal that no one wants, the exchange’s contracts could be priced differently from the rest of the global market.

Already, Trafigura has been delivering Russian copper to LME warehouses in Asia in recent days after failing to sell it in China, Bloomberg reported.

The two copper committee members who voted against a ban—representatives of China’s Minmetals and IXM, a trading house owned by China Molybdenum Co.—argued that it wasn’t the LME’s place to impose sanctions, and that doing so would disrupt an already febrile market. A third, from French cable maker Nexans SA, abstained, according to people familiar with the matter.

The LME committees only have an advisory role. But the exchange is also wrestling with the issue: Chief Executive Matthew Chamberlain told Bloomberg TV the LME wanted to make sure it “can’t be part of financing any type of atrocity,” and was in talks with governments.

The LME has said it will not impose restrictions on Russian metal that go beyond government sanctions. Still, any move by the U.S., U.K. or EU to target Russian metal flows would probably lead the exchange to block new deliveries.

On Friday, the LME made the largely symbolic decision to ban deliveries of newly exported Russian aluminum, copper and lead from its warehouses in the U.K., in response to a new import duty imposed by the U.K. government.

“The western world is going to have to work out ways of using less Russian metal,” said Duncan Hobbs, research director at metals trader Concord Resources Ltd. “We will see some redistribution of trade flows as a result of what has happened, even if the fighting stops tomorrow.”