China’s increasingly extreme Covid Zero policies are standing in the way of a full recovery for the shipping industry and prolonging a crisis that’s snarled ports and emptied shelves worldwide.

In its attempts to keep the virus out, China’s continued to prohibit crew changes for foreign crew and recently imposed as much as a seven-week mandatory quarantine for returning Chinese seafarers. Even vessels that have refreshed their crew elsewhere have to wait two weeks before they’re allowed to port in China.

The world’s biggest exporter, China is a key hub for the shipping industry. It is also the last country to hew to a Covid Zero policy, with increasingly radical measures. In recent weeks, authorities locked in 34,000 people at Shanghai Disneyland for mandatory testing. A Beijing school held primary school children overnight after a teacher tested positive. The definition of “close contact” now extends to people separated by as much as a kilometer.

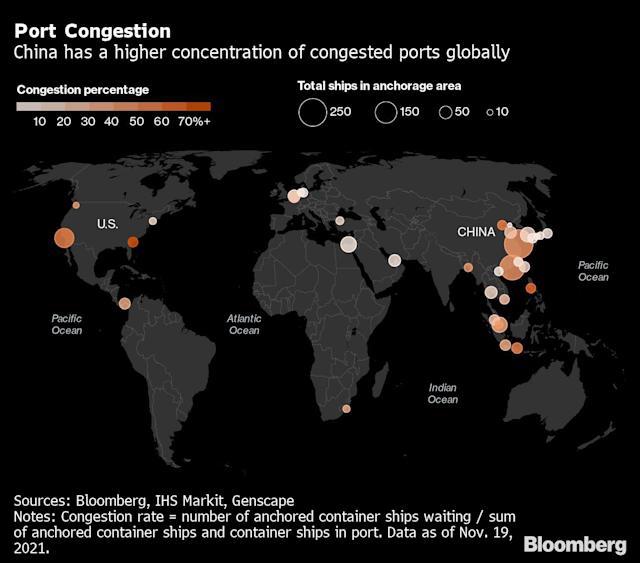

Around the world, factories, shipping and consumers are still adjusting for a pandemic that’s not going anywhere. Supply shortages are showing signs of easing in the U.S. but worsening in the U.K. Some ports in Asia are getting less congested, but in California, loaded vessels are still piling up.

Ship managers and operators are calling for China to relax its restrictions and governments to prioritize seafarers and shipping, or risk continued disruptions that may go deeper as mariners bear the brunt of the toll.

The latest restrictions at China’s ports target Chinese crew, requiring them to quarantine for three weeks before their return to China, then another two weeks at the port of arrival, and two more weeks in their province before they can reunite with their families, according to Terence Zhao, managing director of Singhai Marine Services, one of the biggest Chinese crew supply agents.

“The ports’ main focus is on quarantine and health matters,” he said at an online industry forum Monday. “The regulations change very often, depending on the local Covid situation.”

Even seafarers with emergency medical needs aren’t allowed to get care in China, ship managers said. An Anglo-Eastern chief officer with a severe tooth abscess couldn’t get off his vessel for treatment. The ship had to divert to South Korea before he could see a dentist.

“China is a major issue,” said Bjorn Hojgaard, chief executive officer of ship manager Anglo-Eastern Univan Group and the chairman of the Hong Kong Shipowners Association. “They are doing a good job at keeping Covid at bay but at the cost of not letting seafarers in—even Chinese seafarers sometimes can’t get back into China.”

Operating in China has become challenging even for the biggest operators, including Cargill Inc.

“We’ve had vessels that ran into demurrage”—late fees—“we’ve had instances where we had to deviate, either before we call China, or after,” said Eman Abdalla, global operations & supply chain director at Cargill. “There are instances where the delays are within hours, but there are also instances where the delays could go on to days.”

Euronav NV, one of the world’s largest owners of oil supertankers, has spent an estimated $6 million handling disruptions related to the crew change crisis, including the likes of deviations, quarantines and higher travel costs.

“In the past, it was pretty nice to do crew rotation when we were in China,” said Chief Executive Officer Hugo De Stoop. “And now basically it’s not possible.”

The industry has largely absorbed the extra costs with some of the highest container rates on record due to demand, capacity constraints and port congestion. At $9,146 per 40-foot container at the end of the week on Nov. 18, rates have soared six-fold compared to the five-year average through 2019. Rates for oil tankers and bulk carriers have not risen nearly as much.

Ship owners and operators also acknowledge that they are managing China’s restrictions by shifting the burden to the workers on board. Chinese authorities won’t allow more than three Chinese seafarers on a flight to the mainland, so their return home can be stretched to months after they’ve signed off from vessels, said Hojgaard.

Anglo-Eastern said as of this week, 555 out of its 16,000 active crew are overdue for relief, and nearly 60 have been on ships for more than 11 months, the maximum mariners are allowed by international law to be on board. “We are trying our best to get them off but can’t,” said Hojgaard.

This month, China’s coronavirus czar defended the nation’s strict covid measures and signaled there wouldn’t be an easing of rules. Meanwhile, the industry’s supply chain disruptions don’t show signs of abating. According to a new Oxford Economics survey of 148 businesses Oct. 18-29, nearly 80% of respondents said they expect the supply crisis still has scope to worsen.

“China is determined to achieve zero Covid and it will not relax regulations due to the policy,” said Singhai Marine’s Zhao. “It may even step up rules due to the winter Olympics in February next year.”

-25-year-extension-_-_127500_-_31e3336ae66616c1378205f46c2112aa6f8c22cd_yes.png)