When President Joe Biden on Jan. 9 issued an executive order to increase competition in the U.S. economy, most of the news coverage focused on what he said about 21st century industries such as the internet and pharmaceuticals. But Biden also had something to say about railroads, which have drawn complaints about monopolistic practices since their birth in the 19th century.

Biden’s order touches on one of the most sensitive issues in freight railroading: reciprocal switching, which is akin to net neutrality for the internet except that instead of electrons it deals with rails, switches, and long trains laden with everything from coal to soybeans. Under reciprocal switching, a railroad can pay a competitor to deliver cars for it to a customer that it has no way of reaching otherwise. Reciprocal switching breaks the monopoly control that a railroad has over its captive customers.

In his executive order, Biden encourages the Surface Transportation Board to look into strengthening reciprocal switching rules if it determines that doing so would be good for competition. The president can’t order the Surface Transportation Board to do so because the agency—the successor to the Interstate Commerce Commission—is independent.

Martin Oberman, the chairman of the Surface Transportation Board, has welcomed Biden’s order while reasserting the board’s independence. His July 9 statement said, in part, “It is apparent that while consolidation may be beneficial under certain circumstances, it has also created the potential for monopolistic pricing and reductions in service to captive rail customers.”

Less pleased was the Association of American Railroads, which said the executive order “throws an unnecessary wrench into freight rail’s critical role” in transportation. “For decades,” it said in a statement, “large corporations dissatisfied with paying fair-market rates to ship products by rail have sought to leverage political influence to change that framework and force railroads to hand over traffic to competitors who might charge less.”

True, regulators can be clumsy and subject to political influence. That’s why economists tend to favor free-market competition over regulation whenever possible. What’s more, reciprocal switching—or “forced switching,” as the railroads call it—is difficult to implement in practice. A must-watch video created by the Association of American Railroads shows that delivering a single car from the siding of one railroad to the siding of another railroad can take 68 operations over six days.

The problem is that competition among freight railroads has diminished since 1980, when Congress passed and President Jimmy Carter signed the Staggers Rail Act phasing out most rate regulation. The Staggers Rail Act improved the financial health of railroads, allowing them to invest more in their trains and tracks. But since 1980, the number of Class I freight railroads in the U.S. has fallen to seven from 33.

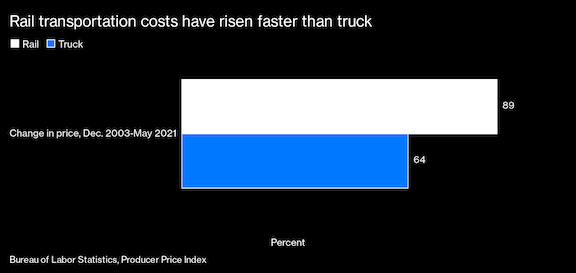

This chart shows that rail transportation has risen in price faster than truck transportation since December 2003 (the earliest date for which I could find comparable data on producer prices from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

The Freight Customer Coalition, which represents big shippers, says that 78% of freight rail stations are captive to a single major railroad and that railroads charge far more to captive customers than to those that have multiple options.

Biden’s executive order lands as the Surface Transportation Board is dealing with the first proposed merger between Class I railroads in two decades. Canadian National Railway Co. has agreed to purchase Kansas City Southern Railway Co., the smallest of the Class I’s. The Surface Transportation Board is weighing whether to approve the formation of a voting trust, which would allow Kansas City Southern’s shareholders to be paid but would keep the railroad independent, under the supervision of a trustee, until the merger review is complete.

Canadian National says its combination would enhance competition with other railroads and trucks, while Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd., which had an agreement to buy Kansas City Southern before it was outbid by Canadian National, says the Canadian National-Kansas City Southern combo would reduce competition. Shares of Kansas City Southern fell 8% on July 8, apparently on speculation about the Biden order, before rebounding 4% the day the order was issued.

Because railroads aren’t allowed to run their trains on each other’s tracks, a particular car may be handed off several times between railroads before reaching its destination. The originating carrier quotes the customer a bundled price that covers what it pays to the other railroads along the route. But the customer has no way to know if the originating carrier is overcharging it. In a regulatory filing, James Cairns, a CN senior vice president for “rail-centric supply chain,” promises in a regulatory filing to extend the company’s practice of giving customers quotes for the cost of each segment of a multicarrier route. He also promises to give customers the option of using another carrier even over routes where it can provide single-line service, saying, “We will use confidential, voluntary, binding arbitration to enforce the gateway commitment.”

That does seem like a pro-competitive commitment. Such commitments would be unnecessary, of course, if facilities-based competition among freight railroads were more vigorous. No railroad would dare overcharge a customer for fear of losing its business. In reality, some routes are competitive and others aren’t. If the Canadian National-Kansas City Southern merger goes through, there may be pressure for yet more consolidation. The more consolidation that occurs, the more the Staggers Act will stagger and customer demands for rate regulation—or, as Canadian National offers, arbitration—will intensify.

By Peter Coy, Bloomberg Businessweek Writer