United Parcel Service Inc. will pay more for labor after replacing a union contract that expires in July. The main question for Chief Executive Officer Carol Tomé is how much more — and if it’s enough to avoid a strike that would throw package delivery into chaos.

In what are likely to be the most contentious talks since UPS workers were on strike for 15 days in 1997, the Teamsters union, which represents 340,000 UPS employees, says it seeks to increase wages for part-time workers to more than $20 an hour and eliminate a controversial two-tiered wage system. On the table will also be demands for air conditioning in vehicles and for blocking inward-facing cameras.

“We’ve got some great arguments on why these folks should be paid,” O’Brien said. “We’ve got a great argument just on how much money the company’s been making.”

The stakes are high for Tomé and the US. UPS delivers about 20 million packages a day in the US, making it the second-largest ground courier behind the US Postal Service. If UPS workers were to walk out, it would likely be impossible for the postal service and rival FedEx Corp. to cover the volume from UPS’s customers, which include Amazon.com Inc. A strike now in the era of e-commerce would have a much bigger impact than in 1997, when most packages were sent by businesses and parcel networks operated five days a week instead of non-stop.

“It’s pretty clear that it’s going to be spicy,” Ravi Shanker, a Morgan Stanley analyst with an underweight rating on the stock, said of the negotiations. He predicts UPS may increase compensation as much as 10% a year.

Investors are eagerly awaiting the company’s fourth quarter earnings release on Jan. 31, when it is expected to provide 2023 guidance and Tomé may face questions about rising labor costs and the potential for shrinking margins from Wall Street analysts.

Wall Street has applauded Tomé, who became the company’s first woman chief executive and first-ever outsider selected for the top job in June 2020. She successfully steered UPS through the pandemic and met the challenge of keeping up with a surge in demand. Margins increased and operating profits soared, jumping 51% to $13.1 billion in 2021 from $8.7 billion in 2020.

Although the boom in home delivery has faded, UPS’s profits remained elevated — thanks in part to higher shipping prices. Tomé has pursued a “better, not bigger” strategy of seeking to focus on the most profitable operations, even going so far as to turn down some lower-margin business from large customers.

The current five-year contract had also kept labor costs predictable, shielding UPS from wage spikes that hurt profit and service at non-unionized rival FedEx. That had given UPS a temporary advantage during the pandemic when home-delivery demand surged and FedEx rushed to hire workers amid a nationwide labor shortage.

Analysts will want to know how Tomé plans to keep customers from preemptively shifting business away from the Atlanta-based courier to avoid a logistics nightmare if unionized employees do walk off the job.

“We want a win-win-win contract for our employees, our company, and the union,” a UPS spokesperson said in an emailed statement. “We have more alignment on key issues with the Teamsters than not. That’s especially true with respect to maintaining industry-leading pay and benefits, and delivering the best service in the industry with the best safety record.”

UPS argues that it already pays its workers, especially drivers, much more than competitors. The average wage for a delivery driver with at least four years on the job is $42 an hour, not counting pension and health benefits, the company says. A typical wage for an experienced driver at rival FedEx Ground, depending on the region, is $20 an hour and usually comes with no benefits. The company also added 72,000 Teamsters jobs in three years through August 2021, which is more than was pledged under the current contract. UPS has about another 100,000 US workers who aren’t unionized.

President of the Rank-and-File

O’Brien said he’s determined to uphold his campaign promises on UPS, the nation’s largest private-employer labor contract, and lay the groundwork to grow Teamsters membership.

During previous negotiations in 2018, then-president James P. Hoffa agreed to create a new class of driver that was paid less and would give the flexibility of also working as package loaders and on weekends. The majority of Teamsters voted against that agreement, but Hoffa ratified it anyway on a little-known rule based on low turnout.

Rank-and-file members angered by that move voted to eliminate the controversial turnout clause during their convention in the summer of 2021, before electing O’Brien to that top job.

Besides undoing the two-tier driver scale, O’Brien wants to boost the starting wage for part-time workers to more than $20 an hour from $15.50 now. His argument is bolstered by UPS’s need to pay above $20 an hour to attract part-time workers during the pandemic in what are called “market rate adjustments.”

O’Brien has a broader goal of organizing more warehouse workers, including at Amazon, and intends to showcase the UPS contract as an example of organized labor’s newfound leverage over employers.

“We’re going to use the UPS agreement as a template to basically say, this is what you get when you work for a unionized carrier,” O’Brien said.

Negotiations on the union’s master contract will start much later than usual, as union locals bargain their supplemental contracts first, O’Brien said. This is a reversal of order, and gives more leverage to locals and reduces traditional pressure on them to settle so the national agreement can take effect. It will also give the union some sense of UPS’s negotiating tactic. Those local talks should all be under way by Feb. 1, he said.

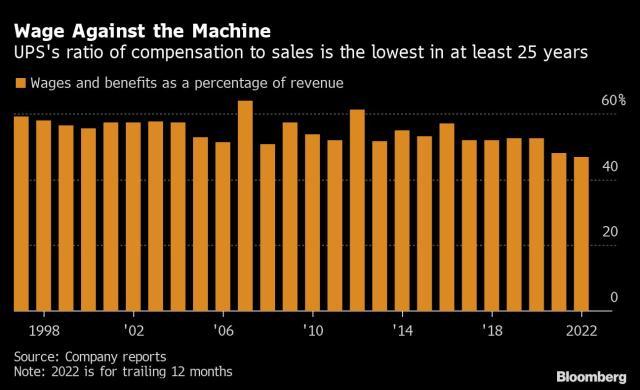

The later start may benefit UPS if by then inflation shows clear signs of abating, said Helane Becker, an analyst with Cowen Inc. who has a market-perform rating on the stock. Becker predicts UPS’s all-in expense for compensation and benefits to increase to 50% of revenue after the new labor contract, up from about 47% now. That ratio had hovered around 52% in the few years before the pandemic swelled sales.

Getting a good agreement will be a key test of Tomé’s managerial moxie, and it’s unclear how much wiggle room the company has. The new Teamsters leader declined to say what the bottom line is for walking out.

“At the end of the day, our members are going to guide us through what’s a strike issue and not a strike issue,” O’Brien said.

_-_127500_-_fd58817006781b0655e77d342459c13ff31c7a97_yes.png)