A confluence of supply chain snags have created shortages in vehicle inventory, but with EVs on the way, what is the future of the auto supply chain?

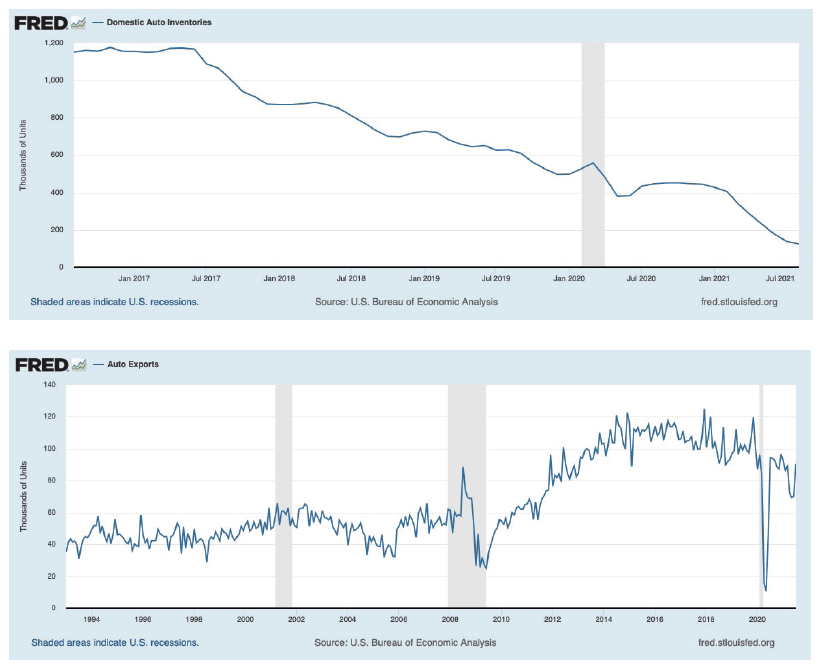

By now, the new vehicle crunch is getting old. Search online for a new Ford Transit van for sale in sprawling Los Angeles, the city of cars, for example, and you’ll get a measly six choices. They come with this advisory: “Due to nationwide inventory shortages, we were unable to find more matches within 100 miles.”

The result: Vehicle factories in North America and Japan alike announced weeks-long factory closures and months-long slashing of production targets. The consultancy firm AlixPartners estimated in September that lost revenue for carmakers globally would reach $210 billion this year, with lost production totaling 7.7 million units. That’s a dramatic increase from just May, when AlixPartners forecast losses at $110 billion and 3.9 million units.

“The state we’re in now is one where there’s no reserve capacity for almost anything,” said Dan Hearsch, an AlixPartners managing director who specializes in automotive supply chains. “So, every little blip that previously would have been almost unnoticeable is now just reverberating” through the system.

As Elon Musk, Tesla Motor’s CEO, said in an earnings call earlier this year: “Things will move as fast as the slowest part of the entire supply chain.”

Structural Changes in Auto Supply Chain

Some of these factors are temporary. Logistics bottle necks should begin to clear. Many supply-and-demand imbalances should right themselves within a year or so, industry analysts believe.

But other issues will have much longer lasting impact on the complex business structure of carmakers globally.

“It will absolutely result in structural changes,” said Hearsch.

Already, automakers are being forced to alter parts of their much-vaunted supply chain and the methods they developed to keep it humming, many involving just-in-time inventory. That change will only accelerate as the industry shifts to electric vehicles and then to self-driving vehicles, which have fundamentally different supply chain priorities. The battery stands at the center of an EV, supported by an array of sophisticated electronics systems. Ford, for example, has said that its EVs require up to 3,000 semiconductors, some ten times the number used in a Ford Focus.

“As there’s less and less internal combustion engine cars being sold, the whole capacity, the whole supply chain will just crumble,” believes Thomas Cullen, analyst at Britain’s Transport Intelligence, commonly known as Ti.

Semiconductors now provide the most obvious choke point for carmakers. “The chip supply is fundamentally the governing factor on our output,” said Musk. “This is out of our control.”

The acute lack of chips stems from a variety of factors. A few are universal, and have impacted everything from iPhones to smart refrigerators. Supply has been constricted as demand has jumped. Fear of chip shortages have, if anything, fueled even bigger orders and longer wait times.

But according to a McKinsey & Co. report, during the first months of COVID-19, automotive suppliers drastically cut orders for chips, as sales plummeted and production slowed. Meanwhile, many consumer electronics makers increased orders to satisfy the sudden shift toward remote work- and connectivity-related equipment. When new vehicle demand unexpectedly surged faster than expected in the second half of last year, suppliers were caught out, as chip makers had “shifted production to meet the demands for other applications,” explained McKinsey.

Chips Hit the Fan

Traditional vehicle manufacturing protocol and needs have compounded semiconductor shortages.

The system works something like this: Automakers don’t order semiconductors, but rely on the various tiered suppliers to do so. Different suppliers are responsible for obtaining different semiconductors, those necessary for the braking system, the keyless entry, the backup camera, the infotainment unit. The list goes on and on. Smaller suppliers don’t order directly from semiconductor manufacturers, but go through distributors. Go down the supply chain and the process becomes more opaque. For their Tier 2, Tier 3 and Tier 4 suppliers, carmakers have little, if any, idea who is purchasing what from whom in what quantities and where the sources are located. Simply put, the further down the supply chain, the less an automaker knows.

The way carmakers order from their suppliers compounds this decentralized approach. While vehicle manufacturers may advise suppliers on what particular models in what trims are coming down the pike in what quantities, they make firm orders only six to twelve weeks before delivery. A supplier that buys a year’s worth of semiconductors in advance not only ties up working capital and warehouse space, but does so at its own peril.

“If I’m the supplier, I’m not going to place orders to my [chip] suppliers that expose me to more risk than what my automaker customer is going to guarantee me,” explained Hearsch.

What’s more, the overall quantity that the industry currently consumes is minuscule compared to the voracious appetite of consumer electronics, especially with the advent of 5G and the Internet of Things (IoT). Vehicles account for a scant 7% of total semiconductors; consumer electronics, by contrast, accounts for 50%.

Finally, the semiconductors that motor vehicles require are anything but leading edge. They are typically made in older-generation fabrication plants with equipment calibrated to produce wafers that are 200mm (8 inches) in diameter. The current state-of-the-art wafers are 300mm in diameter, which translates into twice the number of integrated circuits that can be etched on a single wafer.

Vehicle-related semiconductors traditionally emphasize durability. Semiconductors used in vehicles must be rugged, able to withstand temperature extremes, and long-lasting. A car is used on average close to 12 years. A decade-old mobile phone, by contrast, is a museum piece.

All this means that the vehicle industry stands near the back of the line. So, yes, there’s a global chip shortage. But it’s much more acute for Ford or Toyota than it is for Apple or Samsung.

The multi-billion-dollar semiconductor plants, now under construction in the US and elsewhere, won’t necessarily end carmakers’ woes, either. These new plants, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.’s $12 billion factory, now under construction in Arizona, are geared to the more sophisticated, higher-value chips.

Chip Crunch and the Future of the Auto Supply Chain

In an attempt to help alleviate the chip crunch, carmakers are, reluctantly, altering the way they order parts. In some cases, they will now guarantee bulk semiconductor orders beyond what is needed for the next 90 days. Some are attempting to negotiate directly with chip producers and at least one, Hyundai Motor, has said it wants to develop its own semiconductor chipmaking.

However, all this takes time. Moving to a new chip supplier requires at least a year’s lead time, according to McKinsey.

What is termed “directed supply” will become much more the norm, analysts believe. In this case, automakers will make agreements and guarantees with chipmakers on behalf of the secondary and tertiary suppliers to better insure adequate stock. This system isn’t anything revolutionary in the industry, but has been only spotty in use and hardly ever with semiconductors. (The exception to the rule is Tesla.)

“You’ll see a lot more of that, where the automakers take their destiny in their own hands, take more control,” said Hearsch.

Greater visibility down the supply chain will be a lasting impact of this current crisis, Hearsch, for one, believes. Carmakers will demand to know where supplies are being sourced, “where is the steel coming from, where is the wafer coming from, plastic, aluminum, everything.”

Hearsch uses the hypothetical example of a natural disaster in Australia. By mapping their supply chain, automakers will know that some of their material comes from an Australian mine in the impacted region. “They can react to it, instead of waiting to be informed of it three months later.”

Detailed knowledge of the intricacies of the supply chain sourcing builds on another long-term trend: Geographic diversification. This is something that carmakers have pursued for at least the last five years. They at first moved to lessen dependence on China, as wages rose and the Chinese economy became more domestic consumer oriented. So, suppliers began to relocate to Southeast Asia or near-sourced to Mexico.

This could well accelerate as automakers seek to spread risk and attempt to mitigate long transit times, made worse by port congestion.

As carmakers move to electric vehicles, these supply chains will be in even greater flux. The contours of the new system have yet to be developed. For one, EVs are built around batteries, not engines. Plus, they’re far more dependent on semiconductors than with internal combustion engines. Most of these are far more sophisticated than used in traditionally manufactured cars. They will become ever more so as autonomous vehicles shift into a higher gear. Tesla, according to Korean media reports, is teaming up with Samsung Electronics to develop an entirely new generation of chip that uses advanced technology in its etching process for use in the AI necessary for self-driving.

“The supply chain of the internal combustion engine automotive sector is regional,” said Cullen. “The geography of the electronics supply chain is global.”