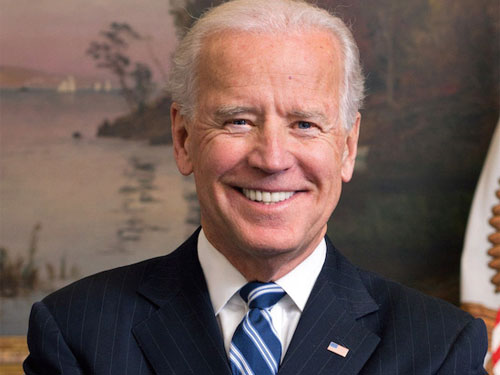

The Biden Administration will have to address numerous trade related issues in the coming months. It’s expected the administration will make moves back to a multilateral trading system but what will that mean in real world terms?

In late December, the Trump administration proclaimed Vietnam as a currency manipulator and threatened to slap steep tariffs on Vietnamese goods bound for the US. Those involved in both countries held their breath. Would Vietnam become the parting shot target of Trump’s long and destructive trade-related wrath?

“Trade has become a very difficult topic in the United States. When Trump was talking in these crude nationalistic terms about trade, there were lots of people who found a resonance in that. So, I think this poses real constraints on the Biden administration,” explained Richard Baldwin, professor of iinternational economics at the Geneva-based Graduate Institute, during an online press conference. He added: “The rules-based multilateral trading system is wonderful and has been 70-years or so, and Trump broke it. It can be and should be fixed. It needs to be fixed.”

Real World Implications

These policies have real-world implications, as everyone in the US from Midwestern farmers to coastal port officials discovered during the tumultuous years of Trump’s trade-related dictates. The changing of the guard in Washington comes at a time when economies around the world still flounder because of COVID disruptions, although many should at least begin to recover in 2021. That, naturally, will boost global trade, with certain categories — car exports and imports, for example — expected to show real gains.

Add to this all sorts of other issues, notably the Brexit aftershocks.

Then, there are domestic pressures and Biden’s own Made In America campaign. Biden himself appears to want to balance the welfare of American business with a desire to re-engage strategic allies and partners elsewhere. He will almost certainly jettison Trump’s unilateral and punitive approach to conducting foreign relations, including trade.

At the same time, the Biden administration won’t radically alter trade policies, at least not yet. It will likely take a deliberate and slow approach to tariffs and other aspects of trade. “The Biden mantra from during the campaign, and still, has been essentially on trade, no sudden moves,” said Bill Reinsch, who holds the Scholl chair in international business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “Don‘t expect the tariffs to go away. Don‘t expect sudden changes. There are all these policies that are being reviewed.”

Here’s a look at some of the major trading partners the Biden administration must grapple with and what it could mean to US exports and imports.

China:

One year back, the US and China inked an economic trade agreement, designed to lower the heat on crackling trade tensions and tit-for-tat tariffs and reprisals. Under the first phase of the accord, China agreed to increase its imports of US goods and services in a two-year period by a combined $200 billion over 2017 levels of $180 billion, the year before the trade war was launched.

The timing of the agreement couldn’t have been worse. Within days of signing, the global economy began to sputter and stall as the COVID-19 pandemic tore through country after country.

Not surprisingly, Chinese imports of American goods came nowhere close to expectations last year. According to estimates fashioned by the Peterson Institute for International Economics’ Chad Bown, China’s two-year commitment “implied” $173 billion worth of goods purchased last year. Yet, China only imported about $100 billion. In the two main categories, according to Bown’s figures, agriculture fell short by $13 billion and totaled just $23.5 billion, while manufacturing turned in a dismal total of $66.7 billion, some $44.5 billion under target.

Will 2021 be a different story? Some believe so.

“One of the things the Chinese do adhere to in their agreements is numerical targets,” said Scott Miller, another trade policy expert at CSIS. “In this case, while the numbers are somewhat of a stretch, given all that’s happened since the agreement was signed, I think they’ll meet the phase one numbers over the two year period. I don’t think they’re ridiculously out of the range of possibilities given the economic recovery in both China and the United States.”

This might be easier said than done, however, and there’s a steep hill to climb. In terms of some American exports, the damage may be difficult to erase. Take soybean exports, for example. According to US Agriculture Department data, soybean exports for the first eleven months of 2020 increased 25% over a year earlier and most of this can be attributed to China. However, 2018 saw soybean exports to China collapse by about 50%, while 2019 was essentially flat. Meanwhile, China ramped up soybean imports from Brazil.

At the same time, Washington will be reassessing the US-China relationship, while Beijing will be appraising what a Biden administration means to bilateral relations. Trade will certainly play a key role. “The prior administration was aggressive in its approach. The Biden administration will continue to be aggressive,” said Laura Siegel Rabinowitz, a trade specialist attorney with the firm Greenberg Traurig. “The optics for the new administration could be that of weakness if they simply reverse the China tariffs and we don’t expect them to do that,” Rabinowitz said.

Reinsch fashions this slightly differently: “Biden would like to make the tariffs go away because he’s sensitive to the damage they cause here and not to just farmers, but manufacturers. But the most fundamental principle of trade negotiation is there’s no free lunch. He’s not going to get rid of them gratuitously. He’s only going to get rid of them if the Chinese are willing to make some concessions that he can pronounce as justifying getting rid of them.”

One looming point of contention is human rights violations on the Uighur in Xinjiang, which is central to China’s cotton industry. Just days before it ceded power, the Trump administration banned imports of Xinjiang cotton, tomatoes and all products made with these raw materials, because of alleged forced labor and other human rights violations. Biden’s labor constituency and his own human rights agenda could make it hard for him to walk back any such sanctions.

“The issue of forced labor is very, very important,” said Rabinowitz. “The Department of Labor has weighed in on it. US Customs is being very aggressive on this issue. So, companies have to be very, very careful.”

Asia Ex-China:

The US-China trade war, China’s rapidly escalating labor costs, and its own push to higher value-added manufacturing, combined to prod both Chinese manufacturers and American importers alike to look elsewhere in Asia for sourcing mass manufactured goods such as apparel. Vietnam quickly became the destination of choice. That caused US-Vietnam business to rapidly escalate and a trade imbalance to swiftly develop.

Trump’s response to the trade gap was to punish Vietnam, but he ran out of time for implementation. Biden’s approach will most likely be more accommodating.

One larger, and longer term question is whether the US could somehow hitch itself to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

In 2017, Trump withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a mammoth free trade zone that linked a dozen Pacific Rim countries and was a favored project of Barack Obama. (Congress never ratified the treaty.) The remaining eleven nations, which include Japan, Vietnam, Australia, Mexico, Chile and Canada, fashioned the CPTPP.

Biden said in the presidential campaign that he doesn’t want to rejoin the CPTPP in its current form, although he left open the possibility of membership if environmental and labor standards are strengthened. That would take a re-authorization of negotiating authority, which expires the end of June, but with the Democrats controlling Congress, it shouldn’t be difficult.

“The script is written for the Democrats. You say the existing agreement isn’t enough. You say, I’m going to fix it. You have a negotiation. You make some changes. You say, I fixed it, and now we’re going to join,” said Reinsch.

Mexico:

In 2019, Mexico surpassed China and became the US’s biggest trading partner. While China regained a slight edge last year, in terms of US bilateral trade, Mexico remains in a strong position. The revised NAFTA, called the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), became effective July 2020, so there’s stability in the free-trade relationship. Near sourcing is increasingly attractive by many types of American importers as a way to reduce transport time and other logistical difficulties. Mexico’s manufacturing infrastructure is extremely well developed, as is the agricultural supply chain.

The auto industry, for example, is now heavily integrated through North America, with highly sophisticated supply chains.

There are some worrying signs, however. “Mexico is doing a lot of things to make investment there more difficult. The level of insecurity is very high, so your costs are going up associated with that,” said Miller, who adds, “Mexico is in a position to take advantage of a lot of things that we’d like to move out of China like precursor chemicals for pharmaceuticals. But they’re not [positioned to do so]”

EU/UK:

At first glance, US commerce with Europe post-Brexit is more an accounting exercise than an alteration in trade flow. Trade with the UK, the thinking goes, should remain the same, but is now separate from the European Union. (See Matt Miller story No-deal Brexit “carnage” for logistics’ sector)

In fact, Brexit could cause some more substantive changes. For one, logistics will become much more complicated. No longer will exporters be able to ship into, say, Amsterdam, and distribute to both the EU and Britain from there. Likewise, those who centered their distribution in Britain must at the very least set up another warehouse in the EU.

In addition, Britain could well lose its appeal to exporters who might choose to focus only on the EU.

What’s more, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s calculus that the UK and the US can fashion a quick free trade pact and neutralize some of the damage of Brexit went out the window when Trump, a vocal advocate of Brexit, was defeated. There’s probably no chance of a free trade agreement between the two even over the next several years.

One nagging trade issue may be resolved, however. Rabinowitz, for one, believes the Biden administration may well try to work out a deal on the retaliatory tariffs on the long-standing dispute between Boeing and Airbus.

Global:

Trump didn’t just levy tariffs on country-specific goods. In the case of steel and aluminum, his administration in 2018 tagged overseas producers pretty much universally with steep penalties of 25% for steel and 10% for aluminum. That impacted China, which is the world’s biggest steel producer, but it also penalized overseas producers elsewhere. In terms of steel, Canadian, Mexican and Australian manufacturers were eventually exempted, but European and other Asian producers, including Japan, Korea and Taiwan, remain stuck.

The result was a disaster for many American manufacturers who relied especially on specialty steel products that could only be sourced from one or two producers. American steel production didn’t rebound, either and is even more depressed now than before the Trump action.

Despite this, many trade analysts believe Biden will be loathed to lift the tariffs. “There’s a domestic constituency in support of the steel tariffs and they’re likely to remain under the Biden administration, though there’s lukewarm to negligible support for aluminum, mostly because of the way it’s affected parts of the U.S. supply chain,” said Miller.

“Protecting the steel industry and US manufacturing is important to this administration,” added Rabinowitz. “I do think that there will be a country by country review and perhaps we see some of those being reversed, maybe with European countries, for example.”