The question remains how long can it last?

Breakbulk carriers and container services have been competing for cargo for at least a decade. Commodities like steel, forest products, and chemicals shifted to containers when freight rates were low and shipping lines did all they could to attract those cargoes. Some automobile carriers poached lift-on/lift-off project cargo from the multipurpose vessel fleet. A downturn in the oil sector also left breakbulk capacity underutilized, leading to a falloff in breakbulk rates.

Migration to MPVs

The glut of container imports has overheated that segment, leading to rate increases, and, combined with container shortages in some places and various other pop-up supply-chain disruptions, has led to a migration of some traditional breakbulk cargoes from containers back to multipurpose breakbulk vessels. The trend, which first appeared in 2020, has become so pronounced that the pendulum is now swinging in the opposite direction, with capacity crunches and rate increases on the breakbulk side.

S&P Global has reported that petrochemical traders in China have switched to breakbulk due to tight container availability and poor schedule reliability. “This shift is clearly visible in purified terephthalic acid—a solid chemical used for making polyester clothing and plastic bottles—where more buyers are switching to breakbulk carriers for shipments to destinations such as India,” a report said. As much as 50% of the product is arriving in India from China on breakbulk vessels.

“Producers and physical traders of metals, agricultural, chemical, and timber products have also been starting to book shipments in breakbulk vessels,” the S&P Global report noted. “On the metals front, the main markets making the switch so far are steel and aluminum.”

Other reports indicate that sawn timber out of South East Asia, which for decades has been shipped in containers, now making their way onto breakbulk vessels. Aluminum shipments are being loaded onto breakbulk vessels in Malaysia and the Middle East. And the Estonia-based freight forwarder CF&S reported it had recently loaded 700 tons of bagged fertilizers, feed, and chemicals from Xingang to Hamburg on a multipurpose vessel.

MPV Growth

The maritime market analysts at Drewry project that multipurpose vessel (MPV) market share will grow 9% in 2021, based largely on the phenomenon of cargo moving from containers and impacted by port congestion. “With breakbulk demand firm and charter rates in the competing sectors at levels not seen for a number of years, shippers returned to the MPV sector for their transport requirements,” said Susan Oatway, a senior analyst for multipurpose and breakbulk shipping at Drewry Shipping Consultants. The sector growth is expected to slow to about 3.5% in 2022 “as supply issues sort themselves out,” said Oatway.

In the meantime, breakbulk has started to see capacity problems and rate increases. “This influx of cargo has led to a capacity squeeze,” said Michael Morland, General Manager Americas at AAL Shipping, a global multipurpose shipping operator. “How long this will last remains to be seen.”

MPV Rates

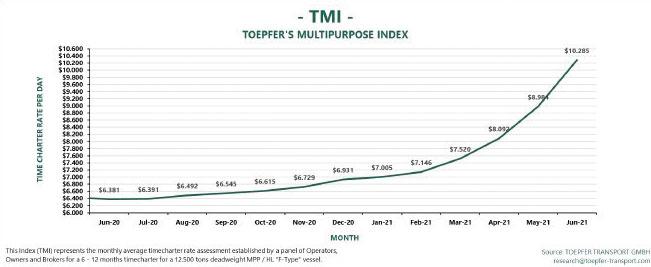

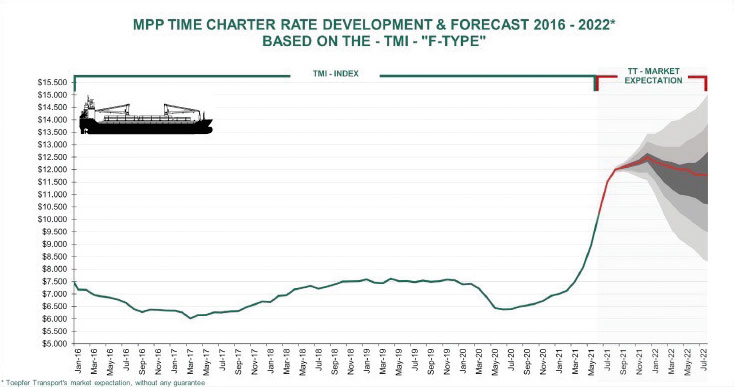

But while it does last, breakbulk carriers are flexing their newfound pricing power. Drewry’s Multipurpose Time Charter Index saw rates increase by 15% in March over February, a 24% rise over 2020, which saw a steep drop in rates. In April, rates increased by another 6.5%, reaching $8,300 per day.

Similar results for MPV charter rates were found by Toepfer Transport, a large ship broker headquartered in Hamburg, Germany, whose index is based on a 12,500 dead-weight ton multipurpose/heavy-lift F-Type vessel for a six- to 12-month charter period. “The demand for cargo space is booming and so are the cargo inquiries for the next months,” said Yorck Niclas Prehm, head of research at Toepfer. “Large operators try to keep the tonnage they have and to add up more, causing only very few vessels to appear on the spot market.”

For some shippers, there is another downside to the current breakbulk phenomenon besides the increasing rates. Breakbulk cargoes generally move on the order of hundreds or thousands of tons per shipment, with larger shipments getting lower rates. That means that breakbulk may be less of a viable option for smaller shippers from a financial standpoint. As Prehm noted, “Small operators who did not secure tonnage in the recent weaker times, have to pay high premiums to secure the ships they need to fulfill their obligations.”

As for the carriers, 2021’s growth is largely “due to port congestion and supply chain issues,” said Oatway, “creating greater effective demand even as overall volumes have fallen in some areas.” That makes the longer-term prospects for growth in the breakbulk segment more modest, although “still positive,” according to Oatway, as container vessel operators reassert competition and reclaim some breakbulk cargoes. “Container vessel operators have put a lot of investment into their project cargo teams,” she said.

“The speed at which congestion and supply chain issues in the container and dry bulk sectors are resolved,” Oatway added, “will have a huge impact.”

Of additional concern to the breakbulk fleet will be its rate of replenishment. “One of the main reasons recovery is fragile for this sector,” said Oatway, “is the level of over-age tonnage in the fleet. Over 50% of the total fleet is over 15 years old. Although the fleet contracted in 2020, our concern is that increased optimism will lead to new investment decisions, without corresponding cargo commitments.”

Morland also cautions “against over-exuberance” in the breakbulk sector. Although he expects “no immediate slowdown in the burgeoning U.S. economy and consumer confidence,” he believes that the industry, sensitive as it is to sudden market changes, “would do well to listen” to recommendations of the U.S. Federal Reserve to proceed with “caution and risk assessment just in case the pandemic takes a turn for the worse and derails the U.S. recovery.”