Dry bulk shipping posted a solid year going into the fourth quarter. But with the Sino-US trade dispute heating up, rough seas could lay ahead.

Although it seems counter intuitive, despite the turbulence of the Sino-U.S. trade war, 2018 has been a solid, if unspectacular, year for dry bulk shipping. What has gone wrong due to the trade dispute between the world’s largest trading economies is well documented – ships full of U.S. soy beans racing against the clock to deliver to Chinese ports before the implementation of China’s retaliatory tariff (see Matt Miller article on page 7). Nevertheless, a lot has swung right, and for much of 2018, the BDI (Baltic Dry Index), a composite of Capesize, Panamax and Supermax timecharter averages, has run ahead of 2017. At this writing (Nov. 19) the BDI was down to 1,023 but for the balance of the year the index has been posting between 1,300-1,400. This is a far cry from the historic high of 11,793 registered on May 20, 2008 but also considerably up from the February 10, 2016 record low of 290.

Fundamentals

The simple reason for the BDI’s performance through three quarters was an improvement of the fundamental underpinnings of the dry bulk trades this year as opposed to 2017. According to a BIMCO (Baltic and International Maritime Council) report, the BDI was up 24%, 25% and 41% in Q1, Q2, and Q3 of this year over 2017. The global seaborne movement of dry bulk commodities reportedly reached record levels in the 3rd quarter of 2018 even with the trade war.

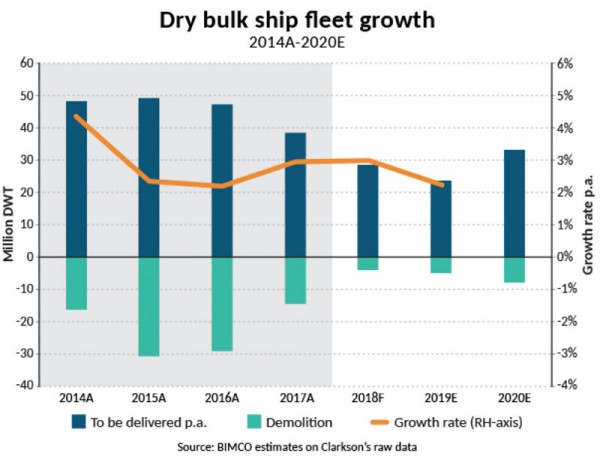

There are two underlying reasons for the year-over-year improvement in dry cargo freight rates. The first is an increased demand for essential commodities as part of an overall improvement in the global economic growth in 2018 over last year. Secondly, the combination of ship scrapping (over several years) and a slowdown in newbuildings (BIMCO says the dry bulk fleet has a net addition of 2.5% year-on-year) has improved dry ship utilization (maritime analysts placing utilization at 87% in the 3rd quarter) and buoyed freight rates.

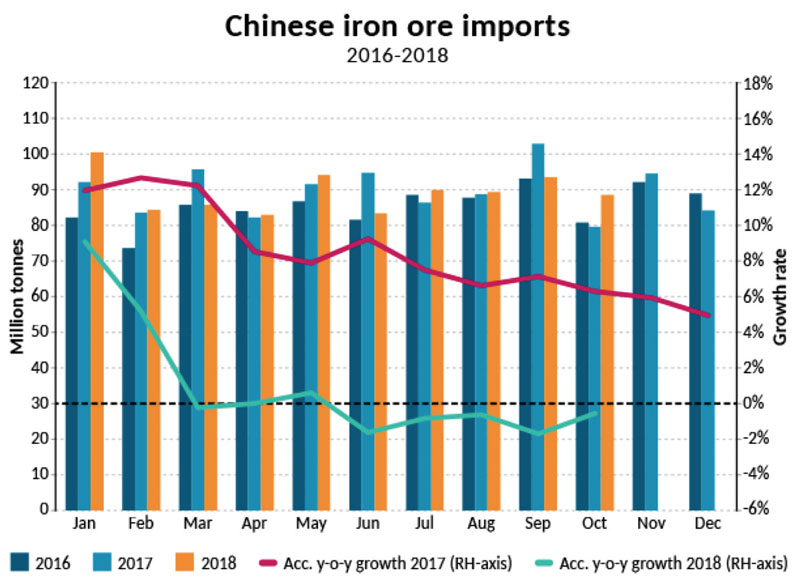

China is always the key driver for dry bulks – just in coal and iron ore alone the country imports a billion metric tons - but the imbroglio with the U.S. didn’t have as much impact through the first three quarters of 2018 as many predicted. From April until November, with only one real dip (when President Trump ordered the review of $100 billion of China tariffs) the BDI was over 1200 and nearly cracked 1,800.

Soy beans are a good example. While China’s retaliatory 25% tariff on U.S. soy bean shipments certainly caused some ink soaking headlines, a majority of the year’s U.S. deliveries had already been made. And the shift to South American based soy producers had already begun. For example, Brazil is expected to ship around 83 million tons of soy beans to China this year. The tonne/miles for shipments of Brazilian and Argentine soy beans to Asia is longer than from the U.S. and has helped keep rates from falling below the dreaded 1,000 point level…for now.

While China prefers U.S. soy beans, they have already begun shifting sources. According to mainland press reports, Beijing has provided incentives for farmers to shift out of wheat into soy to boost domestic production. However, the shift in cultivation could leave a wheat short-fall in the future, creating an increased demand for grain imports.

Forecast: Headwinds

On November 30th, the G-20 meeting is set to convene in Costa Salquero, Argentina where the two principals in the Sino-U.S. trade war, President Donald Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping are set for a tete a tete.

With U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports set to rise on January 1st and an inevitable response from Beijing anticipated, the stakes are high not just for the principals but all members of the global trading community. The preliminary meetings in Washington, DC collapsed following an escalation in the rancor of the dispute increasing the uncertainty of resolution before the next round of tariffs.

Hong Kong-based newspaper the South China Morning Post reported that White House Senior Adviser Peter Navarro – author of the book “Death by China” – won’t be attending the Trump-Xi Jinping meeting. Whether Navarro’s absence is a signal by Washington of a willingness to negotiate with Beijing is uncertain. It’s possible that Trump and Xi make a deal that at least reigns in the tit for tat tariff exchange.

However, even if the dispute is dialed back there is no guarantee that global trade will perform at the same level in the fourth quarter and in 2019 as it did in the lead up to the spat.

There are headwinds building that could send the dry bulk rates tumbling into the triple digit range in the near term. Will the net dry bulk fleet growth be under 3% in the near term? BIMCO is forecasting 2.9% fleet growth for 2020. At the moment, much of the tonnage due for delivery this year has been pushed into 2019 keeping cap on the supply side with fleet growth forecast at 3.7% this year, 5.6% in 2019. This forecast could easily change over the next fourteen months with an increase in deliveries and a bigger order book. Equally, ship scrapping has slowed as the demand for scrap metal has declined.

On the demand side, the real question is whether the big economies like the U.S. and China will continue to grow? The U.S. has posted two back to back quarters of 3% growth (3.5% in Q3 and 4.2% in Q2) and should holiday shopping push the numbers high enough (around 70% of economic growth is consumer generated) then the U.S. could post a 3% growth average for the year – something that hasn’t happened since 2005. But there are also more temperate forecasts.

For instance, in November, Goldman Sachs forecast “a fading fiscal stimulus” along with higher interest rates will slow growth in 2019. Goldman Sachs is estimating quarterly growth of 2.5%, 2.2%, 1.8% and 1.6% next year.

Predicting growth in China is equally problematical as a great deal is tied to increasing domestic demand to help balance out export oriented growth – a difficult task when in a trade dispute with the largest trade partner. IMF is forecasting 6.6% growth for China in 2018, as compared to 6.5% in 2017. But both OECD and World Bank have the GDP falling over the next two years – estimates that ignore the potential fallout should the U.S. and China fail to reach some accord. For dry bulk shipping this could mean some choppy sailing ahead.