In early August, a derecho – a storm with winds upwards to a 100-miles per hour – cut a 250-mile long swath wreaking destruction through Midwest states. Miles of flattened crops, crushed grain bins, downed power lines, damaged residences and toppled trees were left in the derecho’s wake.

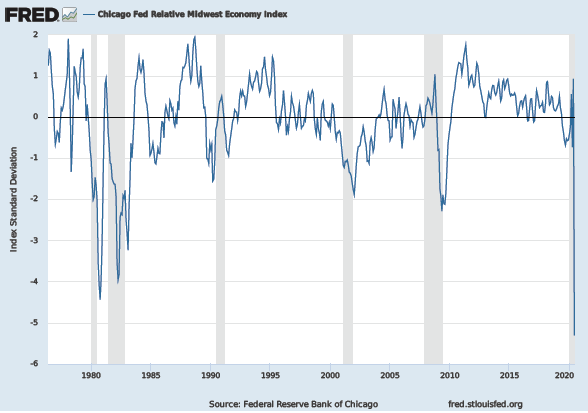

In some ways, the storm was analogous to what’s happened to the Midwest economy over the last couple of years – buffeted by the whirl winds of the ongoing global tariff wars, the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and battered by crop killing bad weather, economic growth has been flattened by this relentless Derecho of misfortune.

One prism through which to view how things are going in the Midwest is the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s monthly AgLetter, which covers the Seventh Federal District composed of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin. The newsletter largely covers the lending health of the region, which includes subjects like agricultural land values and crop pricing – a sort of Farmer’s Almanac of numbers on agricultural economic performance and local conditions.

In the August newsletter, noted that credit conditions had weakened with the onslaught of “adverse conditions” compared to the same period last year – which itself was tough for the region: “Given the widespread adverse effects of the pandemic in the second quarter of 2020, unsurprisingly agricultural credit conditions for the District weakened compared with a year earlier. For the second quarter of 2020, repayment rates for non-real-estate farm loans were again lower than in the same quarter of the previous year. The portion of the District’s agricultural loan portfolio reported as having “major” or “severe” repayment problems (8.3%) had not been higher in the second quarter of a year since 1988.”

Despite the obvious financial distress for the region’s farmers, the AgLetter reported a surprising strengthening (but modest) of farmland values – up 1% over the same period in 2019 – in the District. According to the Chicago Fed, “This uptick broke a streak of year-over-year declines in real farmland values that had extended back six years.”

And there is a caveat to the [relative] strengthening of farmland values. The Federal government has buoyed the region’s agricultural bottom line with the Market Facilitation Program (MFP) designed to help deal with lost farm income from tariff induced cuts in exports and the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP). According to the Chicago Fed, by the end of June, the CFAP had already dispersed nearly $1.3 billion to farm operations in the five states of the District or roughly 27% of the almost $5 billion dispersed by the Federal government. Overall, the MFP – a program largely created by Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue to circumvent the need for Congress to approve the budget – has already committed $22 billion to farmers. While the MFP and the CFAP have certainly contributed to economic stability in the region, the question remains how long will the programs prop up the economy in the Midwest?

Midwest Relief?

Even with the derecho damage to crops, agricultural commodity prices have remained low – with the exception of proteins, like beef, pork and poultry. Two factors have been instrumental in undermining agricultural commodity prices, the drop in corn-based ethanol demand for gasoline and exports to China.

Back in March, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue in testimony before the House Agriculture Committee said “I’m telling farmers to do what they’ve always done and plant for the market. I’m telling farmers not to anticipate one. Don’t expect one. We know there will be some weaning pressure here as people have become comfortable with that. Our goal is not to continue a Market Facilitation Program [MFP]. If we see trade increase and prices don’t go up, that’s a market signal to farmers who are producing too much.”

However, with the election coming in November and the ongoing economic crisis in the heartland, more farm relief money is going to be moving to the Midwest – the question is only how much and to which programs.

Perdue recently said the Department of Agriculture would be able to utilize an additional $14 billion that Congress approved for the Commodity Credit Corporation. And the USDA is saying CFAP 2 – in which the USDA retained a 20% balance to ensure adequate funding – is expected to be applied in early September.

At this writing [Sept. 1st] Congress went to recess without inking a new Covid-19 relief package – the House version of the bill (HEROES) calls for around $33 billion for agriculture while the Senate’s version (HEALS Act) would approve $20 billion. Most beltway pundits think the deal will fall someplace in the middle.

China is a big factor in how fast and from what sectors the Midwest recovers. The Trump administration deal with China calls for $36.5 billion in agricultural and seafood purchases in the first year. Around six months into the pact, China had purchased only about 25% of the tally but in recent months, exports of corn, soybeans (as of August 6th 16.9 million tons had been sold) and other ag products has accelerated. How much China purchases in Phase 1 and whether Phase 2 is ever implemented remains to be seen.

Wider Concerns

Among the many problems facing Midwest farmers is the possible dropping of supports for corn crops to be used in the production of ethanol. Perdue remarked that there simply might not be enough Federal subsidy money to continue supporting the program but there are deeper concerns.

In June, the University of Missouri’s Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) released their Baseline Update for U.S Agricultural Markets which outlined the situation, “Widespread shelter-at-home orders as a result of COVID-19 sharply reduced motor gasoline demand. Within a year, biofuel policy allows ethanol mandates to fall with unanticipated demand declines, cutting domestic biofuel use. Falling oil prices also provide headwinds to ethanol exports. As a result, corn used for ethanol production for 2019/20 is the lowest since the drought year of 2012/13, when corn supplies were the limiting factor.” Without support, switching crops is the only alternative but that doesn’t take care of the here and now.

Of course, there is the lingering problem with the China-US trade deal: Beijing (or Washington) can turn off the tap just as quickly as it was turned on, leaving Midwest farmers vulnerable to planting for a market that might vanish overnight. And finding alternatives to the China market won’t be easy.

Another concern is the potential fallout from the farm payments themselves. While Perdue may want to “wean” farmers from Fed bailout money both parties are intent on making sure the programs continue unabated and well-funded. As well intentioned as the relief funding may be, the programs could lead to problems with the nation’s trade partners.

Back in 1994 the World Trade Organization (WTO) – of which the US is a member – set an agreement that caps “trade-distorting” subsidies to agricultural. Under the WTO agreement, a nation isn’t allowed to subsidize a specific commodity over a 5% threshold of the total value in a single year. In the case of the US, the USDA estimates that farm sales in 2019 crop year will be approximately $378 billion putting the threshold around $19 billion. While not all programs count against the cap, – Agricultural Risk Coverage, Price Loss Coverage, crop insurance premium subsidies, MFP, and some Coronavirus Food Assistance Program, or CFAP, payments – could potentially count, putting the US over the WTO cap. Estimates put US government assistance to farmers at over $34 billion for 2019 and the prospects for US farm subsidies exceeding the cap in the 2020 crop year appear all but assured.

While the agricultural subsidies aren’t going to be up for WTO review until after the year 2022 –the first year when the US will have to report the figures. And it could be years before WTO makes a decision (consider the Boeing case against Airbus took 16-years). But the fallout could be significant as trade partners under the WTO would be allowed to put tariffs on a wide variety of US exports such as vehicles, drugs, electronics and even… agricultural products.

At this juncture, two years seems like a long time from now. And in the interim crops and markets could recover but down the line, there may well be a price to be paid for propping up the agricultural sector in the Midwest.

_-_127500_-_1da204f56eddee4a9ff1d6f8fe7f7f4e89a54723_lqip.jpg)