The demand for U.S. agricultural products is booming. But the future may hinge on a fragile deal.

Corn’s popping as exports to China surge in the post-pandemic boom. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported May 18th that 1.36 million tonnes of U.S. corn had been sold to China for delivery in 2021-22 [the marketing year starts on Sept. 1st]. The new deal brings the sale total to 3 million tons of corn sold to China in just over a week. The Chinese sales also boosted the price of corn to $6.52 ½ per bushel, according to CBOT (Chicago Board of Trade). In brief, it was a nice week for corn in what is shaping up as a nice year. The USDA are now estimating that exports for the 2020-2021 market year will hit a record 2.7 billion bushels, up from export forecast of 2.15 billion bushels made in May of 2020.

Rosy USDA Export Forecast

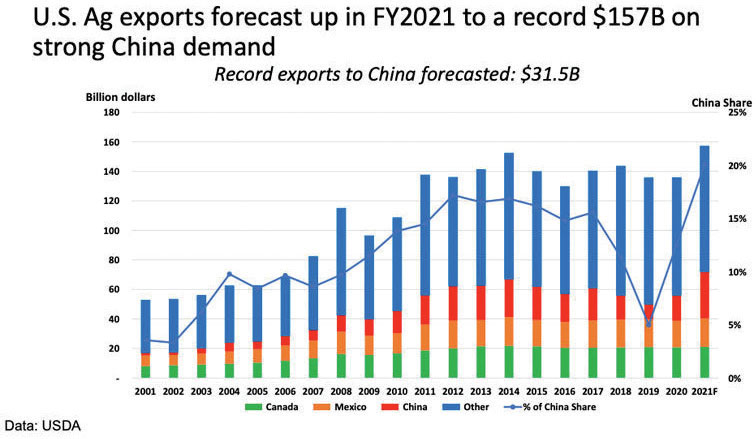

The USDA’s agricultural export forecast is rosy for the post-pandemic surge. Ag exports for Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 are projected at $157 billion, up $5 billion from the November 2020 forecast. The USDA forecasting soybean exports at $1.1 billion higher than in the November forecast to a record $27.4 billion. Not unexpectedly, this uptick is due to strong demand in the PRC (People’s Republic of China) and an accompanying boost in prices. Soybean meal exports are projected up $700 million, while total oilseed and product exports are forecast at a record $38.3 billion, a $2.0-billion increase from the previous projection. Overall grain and feed exports are forecast at $37.8 billion, $2.2 billion higher than the November forecast. Cotton exports are forecast up $600 million on higher unit values and volume. Livestock, dairy, and poultry exports are forecast up $300 million to $32.6 billion, as increases in beef and poultry product export forecasts more than offset declines in dairy products. Horticultural product exports are projected to remain unchanged at $34.5 billion.

Exports for China are raised $4.5 billion from the November forecast to a record $31.5 billion due to strong first quarter shipments and surging sales, most notably the aforementioned corn. China is forecast to remain the largest U.S. agricultural market in FY 2021, followed by Canada and Mexico.

Opening the tap for ag-commodities to China

China opened up the tap to U.S. agricultural goods with the signing of the Phase 1 trade agreement with the previous Trump Administration. Under Phase 1 of the agreement, China was to purchase $12.5 billion in agricultural products above what they purchased in 2017 – designated the last normal “year” between the two trade partners before the tariff trade war ignited. Of course, neither side at that moment knew what was in store with the COVID-19 pandemic looming. In the base year of 2017, the U.S. exported to China $20.8 billion in designated products covered by the Phase 1 terms of agreement. This would mean that in 2020, China would import $33.4 billion in U.S. agricultural products to fully meet the terms of the agreement. Or about a 60% increase in dollar terms over the 2017 ag export baseline. Further the agreement stated that over the course of 2020 and 2021, total exports of U.S. agricultural products to China would increase by $73 billion.

As expected by many prognosticators, China didn’t meet the goal of the agreement in 2020.

USDA data for 2020, stated that U.S. ag exports to China as covered under the agreement approximately totaled $27.2 billion in 2020 or about $6.5 billion over exports in the 2017 baseline year. This was well short – around $6.2 billion – from the agreement’s target.

On the other hand, it was a very good year for farm exports to China. Ag commodities like pork at $2.1 billion, poultry at $761 million, nuts at $705 million set records while corn $1.2 billion and wheat at $570 million posted much better results than in 2017.

But as 2021 reaches the near halfway point, while China remains the largest U.S. agricultural importer it will probably again fall short of the import goals laid out in the agreement.

The USDA raised its forecast for total (this includes more products than under the agreement) ag exports to China by $4.5 billion from the November 2020 forecast to $31.5 billion.

This poses a quandary for the Biden Administration, which inherited the deal. Should they push more aggressively for China to fulfill the obligations of the agreement or adopt a more lenient approach given the qualified success of the deal? After all, China’s opened the tap to U.S. imports, albeit not exactly on the level agreed upon.

The problem is that in terms of trade – especially the China trade – nothing happens in a vacuum. Just ask Australia.

In May of 2020, China imposed anti-dumping duties of 80.5% against Australian barley – effectively ending Australian exports of barley to China. Beijing’s claim was that Australia “dumped” the barley which hurt China’s domestic Barley producers.

In November of 2020, China’s commerce ministry announced the results of another “dumping” probe and slapped duties of from 107% to 212% on Australian wines and followed it up with an additional temporary tariffs of about 6.3% to 6.4% on the wines. The duties have all but wiped out Australia’s wine export business to China. There are a host of other Australian commodities that have been subjected to tariffs, quotas and informal barriers as the relations continue to sour between the two nations.

While few believe China’s allegations carry any merit – the tensions between Beijing and Canberra in other spheres is well documented and China doesn’t appear to be in a rush to resolve these matters before the WTO – the demonstration shows that while it may be hard for Beijing to open the taps for import flows, closing them is exceedingly easy. Whether this acts as a warning to Washington on just how fragile a deal is in place or serves as incentive to broaden the trade horizons, is an open question.