On October 25th TradePoint Atlantic and Terminal Investment Ltd. (TIL) announced a joint partnership to build a 165-acre container terminal and on-dock rail facility. The proposed container terminal is the latest venture in the redevelopment of the site of the former steel mill on Sparrows Point in Baltimore. The new container terminal is destined to complement the multimodal logistics and industrial enterprises that have risen from the ashes on TradePoint Atlantic’s 3,300-acre site.

It is not hyperbole to say that the construction of a new container terminal on the U.S. East Coast is a big deal. Kerry Doyle, Tradepoint Atlantic’s managing director noting the importance of the deal said, “This is one of the most important and consequential announcements we have made since setting out with our initial plans to redevelop the former Sparrows Point Steel Mill.”

The East Coast market share of container volumes heading to the U.S. is forecast to rise with the shift in the sourcing of Southeast Asia and the nation’s problematic relationship with China. And where the new container capacity will be added is problematic on the heavily populated U.S. Eastern Seaboard.

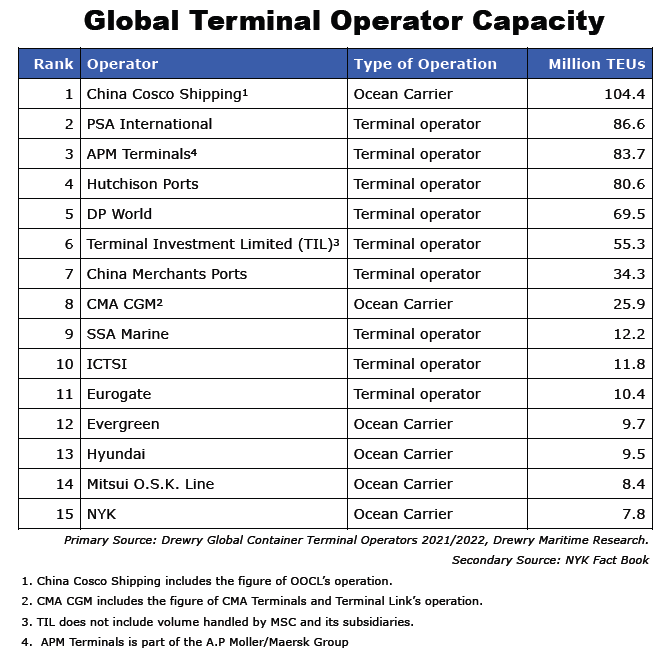

But this is not just about the East Coast, the U.S., or even North America, global terminal operators (GTOs) are searching the world over to find the right locations to add to their terminal portfolio. The GTOs are forecasting a new wave of containers heading their way and they are seeking new opportunities for investment.

Watershed for GTOs

In many respects, this post-pandemic period could well be a watershed moment for the twenty or so GTOs, which constitute a very small club with enormous clout in container shipping. Unsurprisingly, like the containership operators, GTOs have experienced a tumultuous yet enormously profitable stretch during the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic over the last two years.

But there are signs the historically profitable run is coming to an end. The deteriorating economic and geopolitical condition has dampened the container trade outlook. Freight rates have already nose-dived.

There are already some telling figures. The Ningbo Container Freight Index (NCFI) a measure of container freight rates by route, pegged the composite Index at 1390.95 down 20.79% for month-to-month and minus 65.68% for the year-to-year tally. The composite Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (SCFI) for November 11, 2022, was off 135.92 points from the November 4, 2022, rate. By way of comparison, the SCFI was over 5,000 at the beginning of the year. And container port throughput numbers are only marginally better than in 2021. Alphaliner in their week 38 [Sept. 19-15] observed, “The top 20 largest container ports in the world handled 194.8 MTEU [million TEUs] in the first half of 2022 versus 192.6 MTEU in H1 2022, a year-on-year increase of 1.1%” The report also noted the decline in carrier liftings, “Collectively, liftings for Maersk, CMA CGM, COSCO, ONE, ZIM and HMM dropped to 50.9 MTEU in the first half of 2022, a decline of 5.5% versus the same period in 2021, and diverging from the 1% increase in port throughput.”

For terminal operators, collectively these numbers and more like them are a clear signal demand is waning and in turn, terminal volumes inevitably will drop.

So, why are the GTOs anxious to expand? While it seems counterintuitive, similar to Wall Street investors buying during a stock market down-cycle, for GTOs this is the key time for strategic positioning for the next big wave of container demand.

And there are a number of indicators that even during this recessionary interlude, global container trade is going to experience another growth spurt….and GTOs are willing to bet money on it.

Containership Orders Soar

There are multiple reasons for the surprisingly expansive approach GTOs are adopting in this down-cycle. To a degree, it starts with the containership operators themselves – many of which have a stake in the terminals they call at.

And to understand the current state of the ocean carriers, it’s helpful to take a step back to the middle of the COVID-19 crisis when global trade had slowed to a crawl amid lockdowns and dwindling demand.

Alphaliner’s weekly newsletter of July 22-28 reported, “The global containership order book, seen as a percentage of the world fleet, has dropped to a historic low point this month, continuing the declining trend of the past few years. As per Alphaliner’s July data, the order book-to-fleet ratio now stands at only 9.4% or 2.21 MTEU [million TEUs]. For the first time in more than 20 years, the global newbuilding pipeline thus fell below the 10% threshold.”

Fast forward, to the present new building order book for box ships. In 2021 the containership operators began a massive building spree that has only just eased off. The current containership order book 7.3 million TEUs with 2.3 million expected for delivery in 2023 and another 2.8 million in 2024. Most of these vessels are either VLCS (Very-Large Container Ships) or ULCS (Ultra-Large Container Ships). And the order book is heavily weighted to Alphaliner’s top 11 ocean carriers (out of the Alphaliner Top 100 list) with MSC being the clear leader with an order book of 125 ships of 1,742,474 TEUs.

The Container and Global Trade

So, why are the carriers so confident in a containerized trade rebound while geopolitical conflicts and global inflationary pressures are driving the world closer to recession?

The globalization of trade and the expansion of the container trade have been closely linked. From the 1990s until the Great Recession (2008/9) global container throughput outperformed the world GDP. However, since 2014, global GDP growth and have moved nearly in tandem. And the current forecast is that GDP will slightly outperform container throughput through 2023.

Drewry in their “Container Forecaster” issued in October is projecting a 1.9% growth in 2023 but 3.5% growth in 2024 and 3.8% growth in 2025.

The containership operators and GTOs fundamentally believe that container trade growth will again outperform global GDP – and the upswing will be evident as early as 2024. Drewry in their “Container Forecaster” issued in October is projecting a 1.9% growth in 2023 but 3.5% growth in 2024 and 3.8% growth in 2025.

Perhaps even more important than the growth forecasts, although containerization is a mature industry over sixty years old, “containerization penetration rates remain low”. DP World in their November investors’ presentation produced a chart supporting their expansion goals entitled “Containerisation Penetration Rates Remain Low”. The chart basically compared port TEU throughput to population (2021) figures. The country with the highest containerization penetration was China at 178 [TEU/1,000] with the “World Average” at 109. Regions like Africa, Russia and India were under 50. And for comparison, North America was 154 while Europe checked in at 136.

From a GTO perspective, these numbers suggest there is still significant opportunity for box volumes to grow and for new terminals to be built.

North America Investments

As the containerization “penetration” numbers suggest, developing nations look like the ideal targets for new container terminals. And that has been the case, as the portfolios of GTOs like ICTSI, DP World, APM, PSA, Hutchinson Whampoa, and others are targeting developing nations. There is even an interesting twist in a $700 million terminal project in Sri Lanka, which is partly funded by India’s Adani Group, the company’s first sortie into the terminal business – a reminder that with enough capital even the highly leveraged terminal business can spawn new competitors. One notable advantage in constructing in developing nations is a better opportunity for “greenfield” build – essentially designing from the ground up a terminal. Rather than trying to fit a terminal into an existing complex.

That’s why Singapore can build a Tuas Port, [which opened in September] which will eventually have an astounding handling capacity of 65 million TEUs. [By way of comparison, in record-breaking 2021, the U.S. ports of New York/New Jersey, Long Beach and Los Angeles handled under 30 million in combined TEU throughput.]

Running somewhat against the trend there has been considerable interest in North America. Besides the recent foray by TIL mentioned above, PSA announced in April that it had acquired Ceres Halifax Inc. [which operated the Atlantic Hub terminal] from Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha. PSA already had a presence in the Port at Fairview Cove terminal. Also, in 2019 PSA bought Penn Terminals [located on the Delaware River] from Macquarie Infrastructure Partners. It was PSA’s first acquisition in the U.S. In February, Ceres Terminals inked an agreement with the Port of Jacksonville to modernize the 158-acre TraPac container terminal. Jaxport and Ceres agreed to a 20-year $60 million lease while in a separate transaction Ceres purchased the previous leaseholder TraPac Jacksonville from Mitsui OSK Line (MOL). In June, DP World made an investment in the Port of St John, New Brunswick Canada in a multipurpose terminal with the aim of modernizing the facility.

The investments in North America, while running counter to the strategy of capitalizing on building new terminals in nations with less container penetration, show the importance of improving positioning on well-trod routes.

In the U.S. market, there are undoubtedly some challenges. Terminal automation is a sticking point for waterfront labor. Both the ILWU are wary of what the “automated terminal” and associated technologies mean to their membership.

Whether in developing countries or industrialized nations, brownfields or greenfield GTOs are planning for the next wave of containerships that will come calling, as any day now they will be on their way.