Can “nearshoring” help relieve the continual growth struggles in Latin America?

In the beginning of February, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published a blog entitled “Latin America Faces Slowing Growth and High Inflation Amid Social Tensions”. The key takeaway from the blog is the struggle for Latin American Countries (LAC) to economically grow. According to the IMF blog, “Growth this year is poised to slow to just 2 percent, amid higher interest rates and falling commodity prices. Job creation and consumer spending on goods and services are both slowing, and consumer and business confidence are weakening. Growth will also be held back by a slowdown in trading partners, particularly the United States and the Euro area. [Editor italics] Moreover, downside risks—including tighter-than-anticipated financial conditions and Russia’s war in Ukraine—continue to dominate.”

And the difficulty for the LAC to sustain GDP growth stands out with the post-COVID-19 economic surge. Latin American economies proved to be hardy during the pandemic but whereas most economies were able to capitalize on the pent up consumer demand coming out of the COVID lockdowns, the gains were relatively modest throughout the LAC.

The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank in April released their annual LAC review, “The Promise of Integration: Opportunities in a Changing Global Economy.” And while the Review lauded the LAC’s ability to weather the COVID years, “Income and employment have largely recovered from the pandemic, poverty has receded, and markets remain guardedly optimistic about the near future” the lack of GDP growth remains a concern adding, “Although numerous global factors can explain the very modest 2023 growth rates, the forecasts going forward predict the same lackluster pace of the past two decades.”

The impact of the tepid GDP growth is made all the starker, “On average, the region [LAC] has fully recovered its lost growth of gross domestic product (GDP), although since COVID-19, growth is below that of all regions except war-torn Eastern Europe, which LAC only slightly exceeds.” To the point, the World Bank Growth forecasts for the LAC in 2023 have been “steadily downgraded over the past six months to 1.4 percent. For 2024, the figure is 2.4 percent, which is expected to remain in 2025.”

Investment and Growth

There is always the lingering question in the LAC of why GDP growth hasn’t matched the promise that comes with robust trade. Certainly, the volatility of export commodities is a factor but even during the periods of upward swings in commodity prices, GDP growth has rarely kept pace nor carried over to the ensuing years.

Most economists believe the key factor holding GDP growth down in the LAC is a chronic lack of investment. The need to address lack of investment both from the public and private sectors was addressed by the IDB at the organization’s annual meeting held in Panama City in March. IDB president Ilan Goldfajin said, at the meeting “We [LAC] must at least double our level of investment in infrastructure.” Goldfajin, an Israeli-born Brazilian economist, believes that investment in the infrastructure will provide the underpinnings to sustained growth, as experienced by other emerging regions — notably Asian economies. According to the IDB figures LAC nation have invested only 1.8% of the GDP in recent decades and less than half the amount spent by similarly placed economies in Asia. The IDB estimates that the LAC needs to invest at least 3.12% of GDP over the next 10 years to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly. The lack of basic infrastructure weighs down economic performance and benefits. The IDB estimates that just 40% of the LAC’s homes have internet, only 66% access to mobile broadband and even more fundamentally, 50% of the region do not have access to potable water and safe sanitation and 20% of the primary paved road network is in poor condition. It is as Goldfajin noted, a “historical backlog” of underfunded work to bring the LAC back into step with the global economy.

And as the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank, points out there is more to answering the capital needs for infrastructure than deeper institutional or governmental pockets – attracting FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) is piggy backed on trading and “trade intensity has largely stagnated, and foreign direct investment (FDI) to most countries has declined.”

US-China and the LAC

Despite the strong headwinds many pundits think there is a strong chance for the LAC to address the GDP “growth” crisis and forge a new regional identity. The global fracas between the US and China has brought some benefits to the LAC – China has emerged as South America’s largest trading partner and seven South American nations are part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – a move that likely wouldn’t have transpired without the friction between the number one and number two economic powers.

China is now the largest trade partner in South America, largely because over a two decade (2000-2020) surge as “trade between China and Latin America grew 26-fold… (increasing from $12 billion to $315 billion)”, according to US Foreign Affairs figures. The relationship with China has also contributed to LAC’s substantial debt problems. For example, Ecuador owes China nearly $5 billion or around 11% of the nation’s external debt. Venezuela has taken an estimated $62 billion in loans since 2007. Overall, since 2005 China’s state-owned banks reportedly have issued 117 loans in the LAC estimated at $138 billion. A large portion of China’s investment is energy and mining [As of 2021, energy accounts for almost $94 billion nearly 34%, infrastructure accounted for $26 billion around 42%, and mining accounted $2.1 billion almost 3%] with terms granting China “favorable access” to the LAC recipients’ resources.

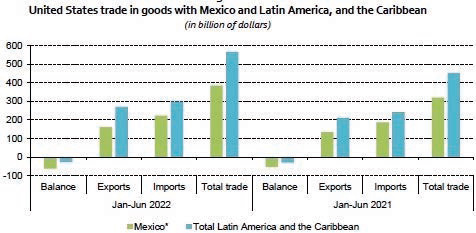

Nonetheless, it’s worth noting that the US is still the largest trade partner to Latin America, largely because of the US-Mexico trade — a two-way exchange that hit a record $779.3 billion in 2022, a 17% bump over 2021.

Reversing the Trend: Is Nearshoring a Solution?

Nearly all the NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) and IGOs (Inter Government Organizations) like the World Bank believe the LACs have a chance to develop sustainable growth through advancing a “Nearshoring” economic agenda. After all, the evidence for the success of nearshoring is right next door in Mexico, which accounts for a whopping 70% of the US trade with the LAC.

Economists point to the “gap” in both the trade policies of both China and the US as grounds for the opportunity. The Biden Administration (as the Trump Administration before it) has made it clear that decoupling from China and an America first manufacturing policy tops the agenda. Although the Biden Administration has given lip service to expanding collaboration with trading groups and organizations, without free trade agreements (FTAs), structurally there is little on the table actually being offered. Similarly, China itself is trying to de-couple from the US by investing in moving its lower tier manufacturing to other nations like Vietnam and Indonesia as an extension of the BRI. Despite the rift between Washington and Beijing, in 2022 the two-way trade topped a record $690 million.

And the question for LAC is, in this new era of Globalization 2.0 (as opposed to the much discussed de-globalization) is there a role to be played as a neutral “manufacturing middleman” when the top two economies want to decouple their commercial relationship?

William Maloney, chief economist for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank, said of the nearshoring option, “The LAC region remains one of the least integrated, while trade openness and FDI flows have mostly been stagnant or decreasing over the past 20 years; countries should find ways to gain attractiveness and take advantage of the nearshoring trends.”

The IDB believes nearshoring could annually boost LACs exports by $78 billion. The IDB forecasts a vast majority of this nearshoring total would go to well-established LAC exporters like Mexico at $35 billion and Brazil at 7.8 billion. But opening the door could revive opportunities for other LACs to be a nearshoring +1 in the global supply chain diversification equation.

And there are other trade opportunities for Latin American countries. In January Deloitte, an international consulting firm, published a Deloitte “Insight” on LAC’s economic outlook in which they pointed out Russia’s exports need replacing in global markets and the LAC is a place to look: “The wave of sanctions on Russia’s products in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine has opened the door for several Latam countries to step in and supply select commodities to international markets. For example, in the fossil fuels market, Russia has been the main supplier of petroleum oil and natural gas to the European Union. The latter is now preparing to stop importing Russian gas from 2027 on. This development would open up opportunities, for example, for Argentinian gas, among others.”

Will nearshoring and trade replacement guarantee sustainable GDP growth in the future. Probably not as there are many other social and economic problems to address, such as equitable taxation. But economic diversification will help the LAC weather the commodity price swings, attract capital and investment which will help underpin the prospects for sustained growth.