Hi-Tech is making inroads in breakbulk and project cargo business.

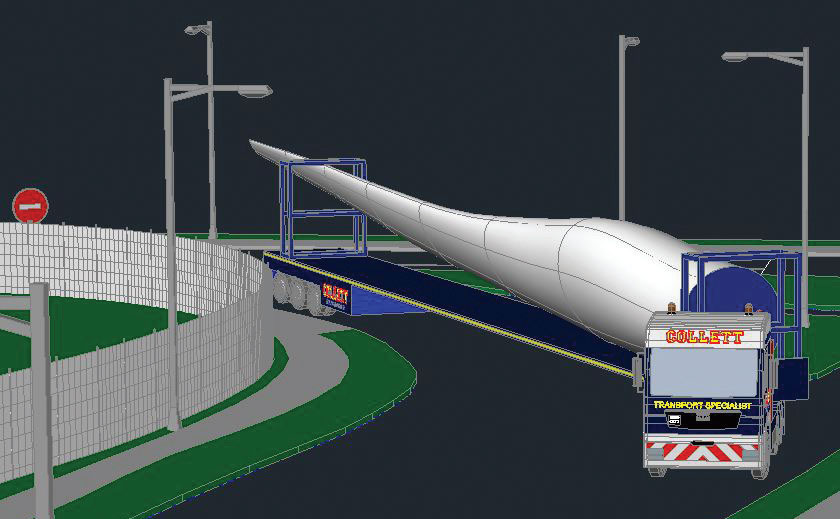

When projects logistics and heavy transport specialist Collett & Sons Ltd. gets an assignment to move a 200-tons transformer or several 60-meters wind turbine blades over the challenging terrain of Britain or other countries in Europe, preparations start at least a half-year in advance.

Meticulous planning is a must for the 90-year-old UK logistics company, based in the West Yorkshire town of Halifax, between Manchester and Leeds. However, it’s planning that draws not only on deep experience, but state-of-the-art technology as well, which both aids and enables the trickiest of moves.

“It’s the practical skills we’ve lived and learned, the sharp end of the stick, that we’re driving to the technology side,” said David Collett. “The customers are demanding more,” he added. “They want us to prove that we can do it.”

Technology is propelling project-cargo logistics on a number of different fronts. Major operators such as Collett now utilize advanced hardware such as the latest generation of Self Propelled Modular Transporters, or SPMTs. They rely on sophisticated, precise measuring devices such as lasers and clinometers (instruments used to measure the angle or elevation of slopes), satellite imaging and complex engineering software. Three-D modeling provides Collett, its customers and authorities with precise, life-like route planning and load specifications, while sophisticated satellite tracking allows those customers to see where their actual cargo is at any given moment.

While Collett and others are making great technological strides, some resistance remains within the project cargo industry as a whole. Part of this is cost, both from the point of view of the shippers and the transport specialists themselves, especially the smaller ones. Part of this is just clinging to outdated methods or an untrained work force.

Project Moves Catching on to Hi-Tech Tools

“If you look at the systems, and look at everything else out there, it’s definitely an area that hasn’t take advantage of the continued improvement of technology,” said Robert Sweatman, director of Logisticus Technology Solutions, a Greenville, SC-based technology services provider, part of the Logisticus Group, which specializes in project cargo services. He compares unfavorably the project cargo industry’s approach to technology with what we consumers consider old hat at home – smart phones and tablets. “It’s not caught up to that,” he said.

Sweatman is quick to add, however, that project cargo providers are changing, albeit with outside pressure. “We’re really trying to bring technology into the industry as much as we can.”

Breakbulk, as a whole, still lags behind containerized cargo in terms of widely used technology that has become an industry standard. “We are receiving ever more enquiries from the [general cargo] market so there is an understanding of the need for software,” said David Trueman, a director at TBA, which provides software solutions for ports, terminals and warehouses, “but there are still many cargo types without unique identifiers such as bar codes or [radio frequency identification] RFID and we still don’t see standard [electronic data interchange] EDI protocols coming through.”

In project cargo transport, each move is almost, by definition, unique. The need for more scientific, detailed and more thorough studies before cargo is delivered reflects an ever-more challenging environment. Loads are becoming ever more massive, longer and heavier. Both clientele and permitting authorities demand certainty. “You’ve got to prove that it’s possible to move these loads from A to B,” said David Collett. “We must write quite complicated risk assessments.”

His company has invested heavily in its own proprietary software, including 3-D computer aided design, or CAD.

This allows an assuredness that protects all parties. Collett surveys, for example, a proposed route for a power generator. The company creates a detailed model, one that includes axle spacing, center of gravity, and ground pressures of each part of the load. It then brings the proposal to the permitting authorities that superimpose the model over their roads and structures. “We don’t know what the engineering is of their bridges,” David Collett explained. “Their engineers have to tell us.”

Say the weight of a particular bridge can’t take the load of an individual axle. Because the company relies on a modular axle system in its transport vehicles, “we might plug some more axles onto [a transport carrier], spread the weight across a greater area, which reduces the overall axle loading,” said David Collett. “One weak bridge, that becomes the common denominator for everything else, we must design a model over that.”

Pinch Points

Weight is one major concern and tight corners is another. These pinch points along a proposed route – road junctions, curves – make clients and authorities alike nervous. They don’t want cargos stuck, equipment damaged or the environment harmed.

“Because we own and operate the actual trailers that will move this cargo, we make our models echo the actual geometry of what the actual physical trailers do,” said David Collett. “We’re 100% sure that when we show the 2D and 3D models, this is what will happen in reality.”

Equipment manufacturers are responding as well to the need for ever-more sophisticated and accurate information. Transport Industry International, or TII, for example, is the holding company of such brands of project-cargo specific transporters as Scheuerle, Nicholas and Kamag. TII offers Salsa Plus, a complex modeling-software that can simulate everything from steering diagrams to load charts to gradients. Notably, the software keys into each individual trailer the companies have manufactured. This gives operators precise information about loads, stability and ground pressure of each chassis.

During the moves, themselves, project builders and operators are beginning to demand more and more information as well. Peace of mind combines with efforts to improve efficiency, whether they be what roads are being traversed to how long a particular cargo is at any point on the route. “We’ve had a customer recently who said, ‘I want to put a GPS on all of my components and if it moves after 8pm I want to get a notification. From our standpoint, these are different technology applications that we’ve been able to bring to the market,” said Sweatman. “We’re finding that it can bring value to the owners of the projects.”