Last September the American Journal of Transportation released a Labor Day Special report entitled Recruiting, Retraining and Retaining Supply Chain Professionals. The report was assembled against the backdrop of unprecedented difficulties to put drivers into seats that occurred with boom in demand following the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing disruptions to the supply chain. Last year, the American Trucking Associations (ATA) projected the 2022 driver shortfall to be at 80,000 and projected with driver retirements that the driver shortfall could rise to 160,000 by 2030. There was among trucking companies, and indeed throughout the entire supply chain, a feeling of dread that the vacancies wouldn’t get filled…or would at a premium.

It’s Complicated

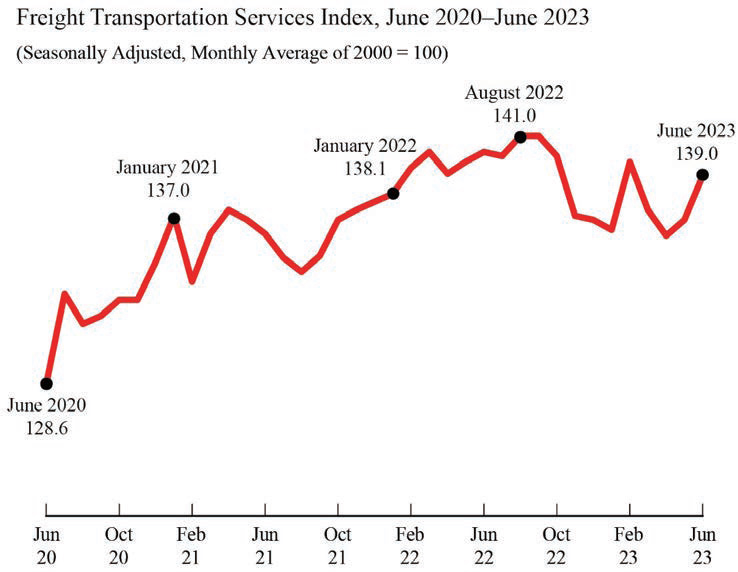

Here in 2023 with Labor Day approaching, trucking freight demand has fallen (albeit a recovery may already be in the works) and consequently the immediate demand for truck drivers has eased.

Last year Randy Mullett, a DC-based trucking industry consultant in an interview with the AJOT, astutely observed, “…our supply chain woes and the driver woes [shortage of drivers] are tied in. COVID wasn’t a new phenomenon, but it was a phenomenon, nonetheless, that tagged to an existing situation…”

That “situation”, Mullett was referring to, was the economy coming out of COVID-19 and how it related to the supply chain and trucking in particular. And at an SMC3 conference in June, Mullet doubled down and observed that if anything 2023 is more “complicated” than 2022.

It takes only a cursory look at the headlines to see the quirkiness of 2023. One week 99-year old Yellow Freight, arguably the largest trucking company in the US, files for Chapter 11, putting 30,000 employees, largely from the Teamster Union, on the street, while in seemingly the next week UPS inks an agreement with the Teamsters that will put their drivers’ compensation up over $170,000 per year in salary and benefits.

Has there ever been a year quite like this?

But to understand 2023 you have to go back to the unprecedented series of events that set all this into motion.

For starters, the post COVID pent-up demand for goods of formerly house-bound consumers burst like a dam and released a torrent of merchandise that overwhelmed the supply chain. Everybody wanted everything that they hadn’t been able to order during the pandemic… and they wanted it right away. Supply chain disruptions — particularly those in Chinese ports like Shanghai, Ningbo and Yantian — aggravated an already difficult situation. Simply put, it was taking more time (and drivers) to accomplish the same deliveries through a stressed supply chain.

It was a chaotic period and logistics companies, for the large part, profited greatly during this once in a generation spike. (For instance, Drewry’s World Container Index (WCI) was over $6,000 per 40 foot container in September of 2022 and peaked over $10,000 per 40 in September of 2021. In the recent August 23rd report the WCI was only at $1,832.48 per 40, even with a 2.3% rebound.)

Then in the middle of 2022 import demand started to fall. But the orders made for the new replacement stocks were often based on assumptions made from earlier experiences. Namely that the supply chain wouldn’t necessarily be able to deliver the items on time; or even more to the point, deliver them at all.

But at the end of 2022 and the beginning of this year, there were fewer supply chain hiccups and warehouses filled up, often in mismatched goods to the cycle (Halloween costumes for Christmas). Soon warehouses were overflowing with goods with no place to go. (For example, Extensiv in their recent 3PL warehouse report noted that “20% of the 3PL warehouses are operating above 100% capacity”). Inventories rose and kept rising and the normal inventory burn-off never kept pace with the weakening demand. Now with 2023 in reaction to the experience of overstocking, retailers are being cautious in ordering, and consequently imports remain low. And consequently, as expected, inventories are slowly coming down. Uber in their 2023 Q3 Market update and outlook, reported “Inventories are trending in the right direction, except wholesalers’ durable goods.” The 3PL noted that “durable goods have exceeded their pre-pandemic levels, and are near historical highs.”

In the meantime, inflation continued to rise, the stock market limped along, but unemployment remained low, and consumers showed surprising confidence in the economy and shifted from buying white goods like refrigerators and washing machines to going out to dinner and more social orientated activities that had been unavailable during COVID. Framing the backdrop to this “stagflation” was the constant reminder through various indices and commentary that the real recession is just over the horizon.

The Common Denominator

Page Siplon, CEO of TeamOne Logistics, has a front row seat when it comes to the economy, labor — and especially to putting truck drivers into seats. The Alpharetta, Georgia-based TeamOne Logistics describes its unique business model as being a “workforce partner exclusively focused on the asset-based transportation and logistics industry.” Much of that business means managing trucks and drivers.

From Siplon’s perspective, the “common denominator” for the economy in any cycle is “transportation and logistics — Big T, Big L.” It is this common denominator, that connects the entire economic eco-system and enables it to function. Something the nation as a whole learned all too well during COVID.

And of course, the key to transportation and logistics is people.

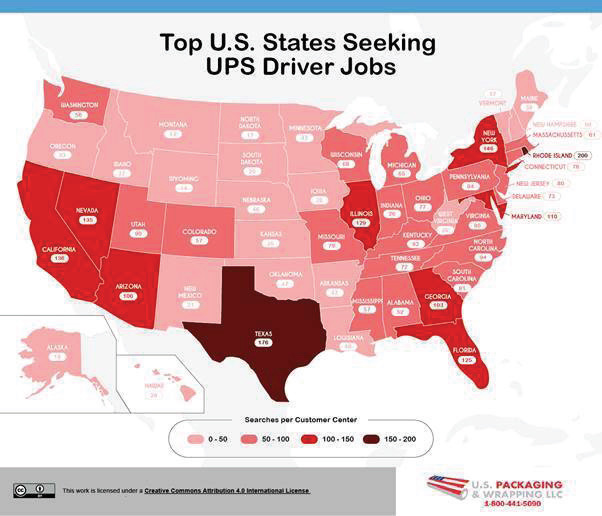

Weakened demand and to a degree less supply chain disruptions have lessened the demand for drivers — in 2022 there was such a demand for truckers that large bonuses, like an NFL signing, were just part of the business of putting drivers in seats — but there are still problems finding and more importantly keeping, professional drivers.

This begs the oft debated question in trucking circles “is there a driver shortage or not?”

Siplon has a nuanced answer to the quandary, “…there’s lots of drivers that are out there. I’ve always said... Some people have different opinions, but there’s not really a driver shortage. There’s a shortage of safe, qualified, professional drivers.”

If anything is clear about the new economy, it is coming out of the COVID pandemic has forever altered the relationship between employers and employees. And that is very true for truck drivers.

“Recruiting drivers has become a little more difficult [in the current economic environment], because people are staying where they are. And if you are recruiting drivers, you’re probably pulling them from somewhere else,” Siplon explained.

But poaching truck drivers or for that matter, anyone in the logistics space, is not easy as the employee expectations are now different. As Siplon points out, “What that means is that a lot of our seasoned professional drivers are looking for more home time. Wages matter. But the first thing that our recruiters and our talent managers hear from drivers… ‘Tell me about the home time. Is it a regional, local job? Because I’m out on the road three, four days a week. I want to be home every night.’”

As a result of drivers’ expectations Siplon says, the business model is changing, “So, people are moving, shifting away from the long haul driver model, especially the seasoned professional drivers that everybody wants, and they’re looking for maybe even taking a pay cut, but looking for more home time, more family time, just because they can.”

Some of the change is generational. As Siplon remarked, the younger generation today that are coming into the industry, at 21, 23, 24, when they’re actually able to meet hiring requirements, they don’t want to be out on the road for a week at a time.”

A New Labor Compact?

A lot has happened since COVID opened the nation’s eyes to the importance of logistics and its most public manifestation — the truck and the driver. From that crucible is a new compact with supply chain labor and specifically with driver workforce, emerging?

Certainly, in past decades it is unlikely with an event like the Yellow Freight collapse, a deal like UPS would have been made. Clearly there is a different dynamic to the trucking business and indeed the entire logistics sector. What might have been okay a decade or even in 2020 won’t fly now.

How does the industry make the adjustment? One way that Siplon sees the industry adapting is through diversification. Virtually, all the big players in the trucking industry have multiple divisions which align with the drivers’ working expectations. As Siplon says of the rise in divisions within the industry, “they [trucking companies] did that because there’s business there and you can recruit drivers. You’ve got a bigger portfolio of opportunities to recruit drivers.”