The gloom. It’s palatable, and it’s understandable. Many Latin American economies were beset with economic problems – some of their own making, many the result of a confluence of global economic conditions – and now the Covid-19 pandemic has replaced what might have been a period of qualified economic growth with the question of whether the 2020s will turn into another lost decade for the region. And the issue of sovereign debt looks to potentially slow recovery.

A Debtor’s Prison

For example, in the case of Argentina, debt has at times undermined the currency [Argentine Peso has largely been falling against the U.S. dollar since 2010] causing inflation and throttling international trade, in a nation with a strong export base. And with debt comes the issue of borrowing and like any individual with “bad credit”, a nation also has trouble borrowing the necessary capital. For Argentina, this meant negotiating a restructuring of $65 billion in sovereign debt with creditors. In early August, after months of negotiations, Argentina managed to get a deal done to avoid the nation’s ninth default. From a commerce standpoint, the agreement will mean lower interest rates and better access to finance, and overall will provide more macroeconomic stability.

Of course, it isn’t just Argentina, nearly every Latin American economy has endured some form of debt and the pandemic has done nothing to exacerbate the issue – some economists are forecasting as much as a 9.4% decline in GDP across the region.

Luis Alberto Moreno, who for nearly the last 15 years was the President of the IDB (Inter-American Development Bank), one of the main sources of sovereign financing for Latin America, cautioned at an early September Atlantic Council meeting shortly before his retirement, that debt across the region “couId be as high as 75% within the next eighteen months.” Moreno noted in his comments that the region’s average debt levels are 58% of GDP and the region’s governments could suffer a severe drop in tax revenues in 2021 with the loss of economic activity due to the pandemic.

But not all debt is created equal. Foreign debt differs from domestic debt in a key way. Nations service foreign debt by exports – either by services or goods. And in the case of Latin America, a majority of those exports are commodities either agricultural or mineral. Even in normal times commodities are subject to wild fluctuations. And these are far from normal times, as the pandemic induced global recession has undermined commodity demand further depressing both the region’s ability to address debt and further sinking the GDP.

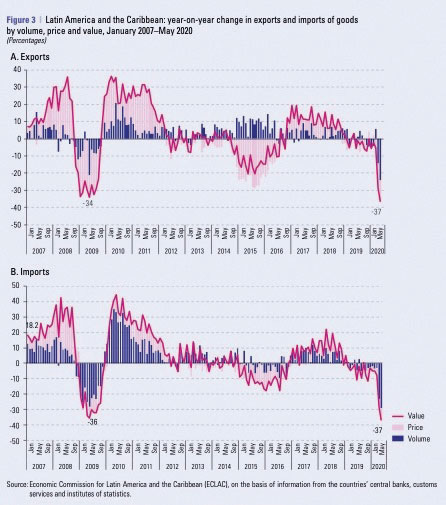

In July, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) released a special report on the economic impact of the Covid-19 epidemic on the region’s trade. The key takeaway from the ECLAC was that “the value of exports and imports of goods decreased by 17% between January and May of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Both flows collapsed towards the end of the five-month period in 2020, with a 37% fall year-on-year in May.” What is disturbing about these numbers is the fall in trade volumes for April and May in 2020 exceeds that of the comparable period in 2009 during the Great Recession [global financial crisis]. The impacts could be severe as ECLAC makes clear, “In the case of imports, the decline is largely attributable to the deep recession the region is going through, with the GDP expected to decline to by 9.1%” in 2020.

US, China and Latin America

Latin America has in recent years become increasingly closer to China through trade and finance. In June, a paper prepared by the CSR (Congressional Research Services), a non-partisan research service for Congress, outlined “China’s Engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean”. The research paper noted China’s investments in “Latin America and the Caribbean during 2005-2019 amounted to $130 billion, with Brazil accounting for $60 billion and Peru almost $27 billion. Energy projects accounted for 56% of all investments and metals/mining 28%. The same data base shows that China’s construction projects in the region were valued at almost $61 billion, with energy projects accounting for almost 53% and transportation projects nearly 27%.” Additionally, the paper noted that the “Chinese banks (China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank) have become the largest lenders in Latin America. Accumulated loans amounted to $137 billion from 2005 to 2019…”

And China’s increasing “engagement” with Latin America through trade and investment has alarmed Washington.

Up until recently, the U.S. has had little to offer as the “America First” policy has had little appeal south of the border. Back in 2018, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made a number of comments to the pool of reporters on his Latin America tour that antagonized Beijing, “when China comes a calling, it’s not always good for your citizens” and “When they [Chinese] show up with deals that seem too good to be true, it’s often the case that they, in fact, are,” and repeatedly warning of China’s “debt trap” policies.

But rhetoric aside, Washington has done little to alter the new dynamic in the rivalry with Beijing. In the aftermath of the Trump Administration’s withdrawal from the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement (FTA) the remaining 11 TPP signatories, which included Chile, Mexico and Peru, concluded the pact without US support. And in the vacuum, China now has FTAs with Chile (upgraded in 2019), Costa Rica (also being upgraded) and entered into negotiations with Peru in 2017. China also supports Venezuela which has become a hotspot in the US-China rivalry in Latin America.

Terms of Engagement

But the terms of engagement may be shifting. In January, China and the US inked Phase 1 of a trade deal. Under the terms of the trade deal, the US agreed to gradually cut tariffs on select Chinese goods, including a decrease from 15% to 7.5% on $120 billion worth of Chinese goods set in 2019. Both China and the United States planned new tariffs that were set to go into effect at the end of the year, however, these were canceled in response to the Phase 1 deal. Perhaps the most important feature of the deal – particularly with the upcoming election literally just around the corner – is the purchase of agricultural products and aims to import $200 billion worth of American goods in the next two years. The plan states that $76.7 billion will be imported in 2020 and $123.3 billion in 2021. While it looks unlikely the PRC will hit the targets, the increase in Chinese agricultural product purchases is underway.

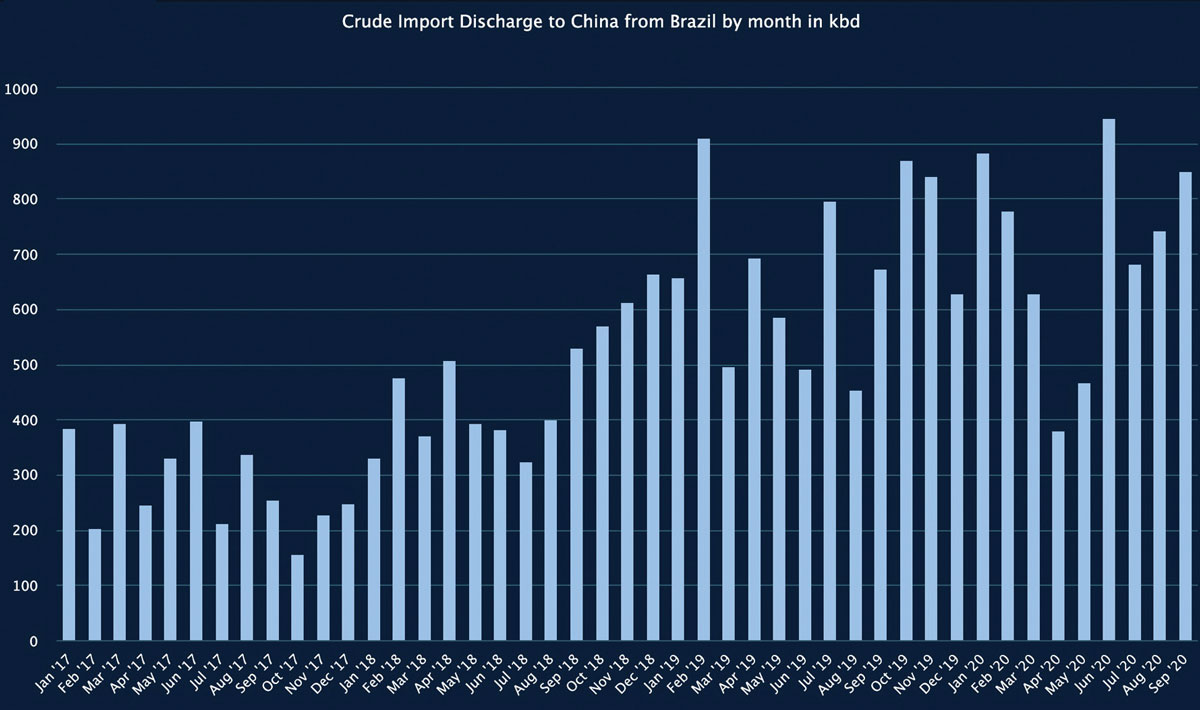

Latin America was a beneficiary of the trade war between the US and China. For example, Argentina and Brazil both increased their exports of soybeans to China as a result. The increased US agricultural purchases by China undoubtedly will impact Latin American producers. The same can be said for China’s purchases of grain, oil & gas and other minerals where Latin American nations are core suppliers.

Another potential shift in the relationship between the US and Latin America, ironically might begin with the iconic IDB itself. With the retirement of longtime IDB head Moreno, the bank elected Mauricio Claver-Carone as the new President. Before his IDB election Claver-Carone was Deputy Assistant to the President Donald Trump and Senior Director for Western Hemisphere Affairs at the National Security Council. In this role, Claver-Carone was the U.S. President’s principal advisor on issues related to Canada, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Washington pressed hard for his appointment as part of the administration’s general push-back against the perceived growing influence of China in Latin America. There is a certain irony in the move as included among the IDB’s non-borrowing members is US, South Korea, Canada and of course, China. In an October 1st interview with the Japanese paper Nikkei, Claver-Carone said that to pull the LAC (Latin America-Caribbean) out of “its worst recession in history”, the region would need “anywhere from $5 billion to $10 billion per year” in loans and guarantees from the IDB, whose capitalization totaled $176.7 billion at the end of 2019.

Still, how the IDB’s leadership will fare under Claver-Carone is an open question, that could become more problematic, should the US voters choose candidate Joe Biden over incumbent Donald Trump in the November election.

And there is the Latin American viewpoint. Does it really have a choice between the US, China or even Europe? The article, entitled “El no alineamiento activo: una camino para América Latina” or “Active Non Alignment as the Way Forward for Latin America,” puts forth the thesis that Latin America could and should adopt a policy of “active non-alignment” as an alternative to being uncomfortably hitched to the policies of either US or China. While not a new notion, the timing – in the midst of a pandemic and recession – might be more difficult to bring to fruition than during the good years, but conversely, is there really an alternative?