Pipelines are multi-billion dollar projects spanning thousands of miles. But beyond the miles and money, there are geopolitical considerations that can stop up a pipe project of any size.

Early this month (note: September), the giant vessel Solitaire began to lay pipe in the Gulf of Finland. The pipe laying is part of the highly contentious Nord Stream 2 pipeline project, which will transport natural gas under the Baltic Sea from Ust-Luga, Russia to Ludmin, Germany.

Meanwhile, Italian authorities dither on whether to allow the completion of a rival project, Trans Adriatic Pipeline, which is being built to carry gas from Azerbaijan to Western Europe. The local populace in the Puglia region of Southern Italy is fighting the pipeline on aesthetic and environmental grounds.

The total cost of these three projects: Almost $30 billion.

“Russia’s geoeconomics has long been successful in keeping the EU divided in its dealings with Russia,” wrote Antto Vihma and Mikael Wiggel, senior research fellows at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, about European pipelines.

In many respects, what we’re witnessing now is a kind of end game. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies in a recent paper predicted the past decades’ steady stream of construction of pipelines, which now crisscross Europe, is winding down, at least for the foreseeable future. “Complexity and politicization will persuade those wishing to bring additional gas to EU countries to do so as LNG, rather than as pipeline gas,” wrote Jonathan Stern, a distinguished research fellow at the institute, in an introduction.

The Complex Geography of Gas

It’s a complicated landscape and also a confusing one. For example, Russian President Vladimir Putin in late 2014 announced the cancellation of the ambitious South Stream pipeline, which would carry gas from Russia via Turkey to Western Europe. This came after the European Commission pressured Bulgaria not to allow the pipeline to cross its territory, most likely a punishment for Russia’s annexation of the Crimea earlier that year. Shortly thereafter, Gazprom initiated TurkStream, with the same goal in mind. The Gazprom subsidiary constructing TurkStream is called South Stream Transport NV.

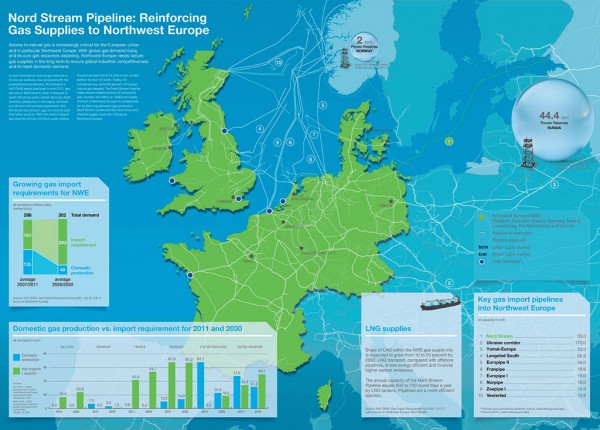

At the heart of all this is Europe’s dependence on Russian gas. This began during Soviet times in the 1980s, when the first Trans-Siberian pipeline was constructed. Since then, numerous pipelines have been constructed and upgraded, and Europe has come to rely on natural gas for both heating and power. The countries of the European Union now consume some 450 billion cubic meters a year. Of this, Russia supplied last year almost 200bcm.

Just about everyone in Europe believes this dependence is unhealthy, but they differ on what to do about it. Germany, Europe’s biggest energy consumer, has angered most of its neighbors with the Nord Stream 2 project, which will up substantially Germany’s reliance on Russian gas. Denmark has signaled that it may object to the pipe passing through its waters, but that won’t submarine the project; Gazprom will merely reroute through international waters.

The European Commission even has rewritten the rules governing pipeline ownership, unbundling pipeline ownership with gas production with what it called the Third Energy Package. The WTO (World Trade Organization) last month upheld most of the 2009 law, although a EU legal directive has said that this can’t be applied to international waters. Once Nord Stream 2 reaches German soil, Gazprom won’t own the facility; it will belong to Germany.

Five western energy concerns, including Shell and Wintershall, have agreed to each lend 10% of the cost of the project. They are termed Nord Stream 2 “financial investors.”

Then, there’s Ukraine, which plays a pivotal role in Russia-related pipeline politics. The two countries have been at loggerheads since 2014, when Russia sent troops into eastern Ukraine.

Russia’s new pipeline projects represent a concerted effort to punish Ukraine by bypassing the rival. Russia’s old pipelines pass through Ukraine, which gains $2 billion in transit revenues every year through a long-term contract that ends in late 2019.

The Russians “very much want to have this pipeline finished and operational before then, because they will have a logically better bargaining position vis-a-vis the Ukrainians,” said Vanand Meliksetian, an energy and utilities consultant with Sia Partners, based in Amsterdam.

Even the US has entered the pipeline fray. In drafting the Russian sanctions-related bills after the Crimea invasion, American legislators dangled the possibility of sanctioning Nord Stream 2, although mandatory sanctions against the pipeline were dropped. Sanctioning Nord Stream 2 was raised again after the Russian interference in US elections. President Trump has railed against Europe’s reliance on pipelines, suggesting American produced LNG would provide a better alternative, although LNG costs much more than piped gas.

TAP Dancing

Breaking European dependence on Russian gas was the motivation for the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, known as the TAP. This pipeline, which is about three-quarters completed, will bring gas from the border between Greece and Turkey overland through Greece and Albania, then undersea to Italy. It’s designed to connect with the Trans Anatolian Pipeline, known as TANAP, which was inaugurated in July. TANAP carries gas from the Caspian Sea fields of Shah Deniz in Azerbaijan to the Turkish-Greece border.

The entire series of exploration, development and transportation projects, known as the Southern Gas Corridor, is one of the most ambitious energy-related efforts in the world today. It’s estimated to cost upwards of $50 billion.

Most believe Italian opposition to TAP won’t derail the project, although if local residents are successful forcing a slight detour, that may delay the 2020 completion date.

TurkStream cuts right into the EU’s effort to wean itself away from Russian gas. TurkStream, if completed, would supply 30 billion cubic meters, or bcm, a year. That’s only half the capacity of the original South Stream, but still will compete directly with TAP. Gazprom claims TurkStream, which is 49% owned by the Turkish energy firm Botas, is compliant with the Third Energy Package.

Already, overcapacity dogs gas pipelines to Europe. According to Meliksetian, last year, some 120bcm worth of Russian pipelines weren’t used. These are older, Soviet-era pipelines that run through Poland and Ukraine and need refurbishing and modernizing to operate efficiently.

However, these pipelines can be tapped, if necessary. Russians already “have the ability to increase exports very quickly to Europe,” Meliksetian said, citing the bitterly cold weather that hit Europe in February. “The Russians more or less saved the day, when they opened the taps.”

The new projects only exacerbate the issue of overcapacity. Nord Stream 2 alone will add 55 bcm, or 12% of Europe’s current consumption. TAP would add another 10 bcm, with the ability to double that in an expansion.

With all this excess capacity, analysts don’t see the need for major pipelines in the foreseeable future, at least for the next 15 years or so. One exception may be a pipeline carrying gas from the Eastern Mediterranean, where large deposits have been found off the coast of Cyprus, Egypt, Israel and Lebanon. An underwater pipeline could bring this gas to Greece and Italy, but such a project isn’t even in the planning stages.

LNG and Europe

Then, there’s LNG. According to figures cited by Meliksetian, European countries already have LNG facilities with a capacity of 208bcm, but only 51bcm were consumed in 2016, the latest figures available. Germany has been the major holdout, although it has plans to construct an LNG facility in Brunsbüttel, near Hamburg. This €450 million project wouldn’t be completed, however, until 2022.

Then, there’s a technical issue, which is pipeline related. Historically, gas has piped east to west, from Russia to Europe. There is, for example, no north-south pipeline.

The plight of the Baltic States is illustrative. Until 2014, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia were completely dependent on Russian gas, as the three nations aren’t connected to the main European gas thoroughfare.

Four years back, Lithuania opened an LNG terminal, which has allowed the Baltic States to reduce dependence on Russian gas by about half. Most of the LNG now comes from Norway, although a tanker made its first delivery of American LNG last year.

The EU wants to develop a truly pan-European gas network. That would involve constructing interconnectors from the Adriatic or North Sea, as well as from Spain to France. It would also mean engineering reverse pipelines, so gas can travel east instead of west. Such a network would make the shipment of gas from LNG terminals much more regional than local, bringing gas to where it’s needed.

EU policy makers understand that “if we have an internal market that is very well connected, it will be so strong that the Russians are not able to exert influence on it anymore,” said Meliksetian.