Ocean carrier alliances are big, powerful… and evolving.

The real structure of the global supply chain resides in the ocean carrier alliances. From an organizational perspective, it is the service schedules within the big three ocean carrier alliances that provide the framework for the global supply chain.

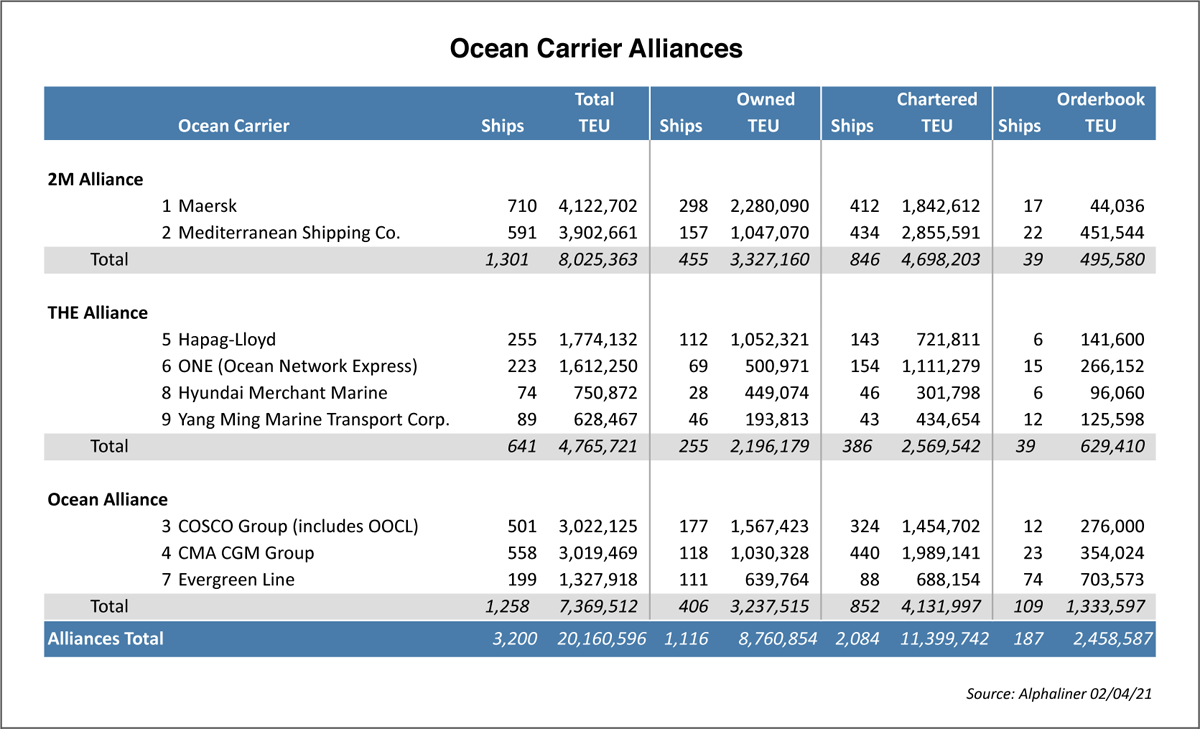

What’s different now – besides the terms by which ocean carriers can act cooperatively without evoking anti-monopolistic retribution – is the concentration of line haul capacity largely into three ocean carrier alliances: 2M, THE Alliance and Ocean Alliance (see chart).

Collectively, the 2M Alliance (Maersk and MSC), THE Alliance (Hapag Lloyd, ONE, Hyundai Merchant Marine and Yang Ming) and the Ocean Alliance (COSCO, CMA CGM and Evergreen) deploy 3,126 vessels with over 20 million TEUs of capacity. This total represents around 80% of the capacity of the containership fleet and an even higher percentage of the line haul capacity.

The big three ocean carrier alliances are composed of nine of the top ten container lines. It is the concentration of capacity that enables the tripartite of carrier alliances to function effectively. For example, the 2M alliance carriers deploy some 1,301 vessels of just over 8 million TEUs of capacity while the Ocean Alliance members have 1,258 ships with over 7 million TEUs of capacity. The Alliance (THEA) is the smallest of the three but still the members command a fleet of 641 vessels of over 4.7 million TEUs. While not all the member vessels operate solely within alliances at any given moment, the sheer size of the collective tripartite gives pause for thought.

Alliance Advantages – Everybody into the pool

Basically, a shipping alliance is the pooling of ships [generally the same type of ships] by various carriers with the goal of running regular style liner services. The advantage of vessel pooling for the carriers is largely one of streamlining scheduling and thus more efficient tradelane and port coverage. With fewer service redundancies, deployments can be made with far more efficient utilization over a much wider number of service loops. Since the business of shipping has inherently high upfront asset costs, collaboration with other carriers with similar service strengths and goals is one of the most straight forward ways of containing costs.

Carrier collaboration within the alliances covers a wide spread of organizational operations. While typical carrier ‘backroom’ work like stowage, scheduling and maintenance are nuts and bolts features of a shipping alliance, capacity planning is what makes the whole alliance system work. The principal mechanism used to assign a carriers’ contributions or slot allocations over various strings is the slot charter agreements (SCAs). The “slots” are chartered by a carrier from another carrier(s) for a specific period of time on a vessel, generally on a designated service route. The slot charterer issues its own bill of lading and for all intents and purposes, the “slot” is part of the carrier’s portfolio.

Although, SCAs are generally thought of as a function unique to an alliance, they also exist between carriers outside the alliances. The same can be said for vessel sharing agreements (VSAs) whereby a ship is “shared” by another carrier and like the SCAs, offers the space under its own bill of lading normally of a specific trade lane.

While the VSAs and SCAs are the glue that binds the alliances together, there are a number of other factors that figure into an alliance. Collectively, the purchasing power of a carrier alliance is much greater than that of an individual carrier, whether that be directed at operational expenses like fuel and port related fees or the purchase or chartering of the vessels themselves. There is also the inherent advantage of commonality in size and equipment which can lower not only the initial purchase price but the maintenance costs over the commercial lifetime of the asset – particularly critical when the asset is a 20,000 TEU ship.

And size is leverage in ways extending beyond operational matters. It is also true when tackling industry wide issues like environmental challenges (IMO 2020 for example) or national legislative affairs.

One major difference in the operation of shipping alliances during this pandemic period is changes in their rotations. In the past, April is the month that shipping alliances readjust their schedule in coordination with their annual shipper contracts period. In the 2021season this doesn’t look to be the case as congestion, high vessel utilization and fewer newbuildings entering service have muzzled changes to rotations. Shipping pundits had anticipated the subdued approach by the alliances as ports jockey for bigger shares of the alliance calls.

According to Alphaliner, the THEA’s reshuffling the East-West loops: the launch of as new direct Asia [US Gulf EC6 service and the expected US East Coast EC1 service increase in vessel TEUs from 8,500 TEU-9,500 TEU to the line haul 13,000 TEU vessels. THEA is also resuming the FE4 loop and replacing the “temporary FE4 extra loader service”.

Landside Perspective

The port perspective is a little different. A port call from an alliance is often an all or nothing proposition. If an alliance decides on a port call, all the members rotate their vessels through the port. Rarely does an alliance member go it alone to a specific port. Thus, the great liability for a port authority is that losing an alliance is really losing a series of calls with little chance of picking anything up from an individual member. In this ‘Big Ship era’ that can happen easily if one member introduces larger ships to the alliance service loop that can’t be handled by a port. There is also prerogative for carriers within an alliance to order and deploy ships of similar sizes on their rotations – again effectively making the alliance a single carrier in terms of scheduling although competing individually for a shipper’s freight.

Another factor that impacts a port’s perspective on an alliance call is how the slots are divvied up among the membership. If say a port is the fourth call in a loop, how many slots are designated for that port call as opposed to the first inbound port?

However, a port also may be the benefactor of an alliances’ investment. Many of the carriers have investments – whole or in part – in container terminals. For instance, Maersk’s APM Terminals, one of the world’s largest terminal operators has around 75 marine terminals in its global network. While it isn’t a guarantee of an alliance call, there is no doubt it improves the chances of acquiring and retaining an alliance call.

For the purchaser of shipping services, the alliance system provides a structural framework – providing a uniformity of services that would be hard to match otherwise. The alliance system – to a point – also provides a backstop against service disruptions that individually carriers would have a hard time matching. On the bigger question of whether the alliance systems are more cost-effective than independent services, it is harder to answer as there is no frame of reference. The supply chain of which the current alliance system is a critical… and even essential, feature is brand new. Today’s supply chain is arguably only a decade old and rapidly evolving with IoT, automation and Ai. And it is within this context that the effectiveness of the alliance system will be measured.

Beyond the Pool

The main function of the alliances remains pooling and capacity allocation, but the carriers themselves are evolving and inevitably so will the alliances. The obvious areas of collaboration involve the development of new fuels not only to comply with IMO 2020 but to lower the environmental impacts to net 0. CMA-CGM has already introduced an LNG (Liquified Natural Gas) powered line haul size vessel, the Jacques Saade (see picture.) But bunkering LNG is problematic and will require an overhaul of the existing bunkering system which is a major undertaking ultimately requiring a “buy in” from more than one carrier.

Fuel isn’t the only question. Ocean carriers are expanding beyond their traditional roles into new service areas – rethinking what the business model for a carrier should be. With the rise of e-commerce will the role of the carrier in the supply chain need to change? Should an ocean carrier be more like a 3PL or even an integrator like FedEx? Perhaps even like an Amazon with the AWS (Amazon Web Services) supporting the consumer oriented edifice. And if carriers do expand beyond their traditional roles will their alliances also do the same? Maersk has already started down this path with TradeLens. What’s beyond the pool – perhaps an entirely new way of viewing shipping.