The Port of Boston TEU throughput dropped 9% to 283,061 TEUs in FY 2020 – so why was that a good year?

When is a bad year good? That’s the question buried in the 2020 numbers for Massport’s Paul W. Conley Terminal, the Port of Boston’s container facility. In 2020 the port handled FY (July-June) 283,061 TEUs [CY 268,418 TEUs] down from the record setting FY 2019 totals of 307,331 TEUs, which had marked the fifth consecutive year that the Port set a record. It looked like the Port was headed for a 350,000 TEU record, setting up the possibility of eclipsing 400,000 TEUs – a once unthinkable number – in the very near future. So, why didn’t the upward trajectory continue?

| Fiscal Year | Import TEU | Export TEU | Empty TEU | Total TEU |

| FY 2020 | 143665 | 75120 | 64276 | 283061 |

| Cal Year | Import TEU | Export TEU | Empty TEU | Total TEU |

| CY 2020 | 137098 | 79133 | 52187 | 268418 |

What happened to the Port, was what happened to us all – the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the regional economics of each area are slightly different and the impacts are different in the Greater Boston area than say the vast Long Beach-Los Angeles metro area.

The Boston area, and indeed virtually the entire freight catchment area for the Port of Boston, is weighted heavily in services, especially the hospitality sector. The lockdowns throughout the New England region contributed to a decline in demand at a number of levels. For example, there are over fifty institutes of higher learning in the Greater Boston area (Route 128 belt) and each year over 150,000 students are added to the City’s population of nearly 700,000. If the semi-circle is widened out a few more miles, it is estimated that student population tops 250,000. With the lockdown, there were fewer students staying in the Boston area which along with closures of restaurants and hotels and the near eclipse of tourism dampened demand for high value consumer goods within the arc. Similarly, exports to global markets were also impacted as each area went through the cycle of openings, lockdowns and re-openings according to the effectiveness of pandemic mitigations.

Massport itself was hit in a number of ways as revenue from Logan International Airport plummeted as flights dropped. Additionally, the 2020 cruise season evaporated like sea smoke with the curtailing of cruise ship calls, and the port was subject to first half bypasses as demand fell.

However, a secondary trend also wedged its way into mainstream economics during the COVID crisis: E-commerce. New England, and really the entire Northeast United States, with high density metropolitan areas and above average household incomes [for example, Boston’s household income is $71,834 and $79,835 for Massachusetts] are tailor-made for e-commerce. And the pandemic’s shift to remote work contributed to an already altered consumer buying behavior in the region

Build It [and Dredge It] and They Will Come

Nearly a decade ago it became obvious that the “Big” ship era was coming and coming fast. Conley Terminal and the navigational approaches would all need a significant upgrade to handle the next (and the next) generation of container ships if the Port was to remain relevant. For Boston, a terminal of dreams (with apologies to baseball’s Field of Dreams) would be able to handle containerships in excess of 13,000 TEUs with adequate main channel depths, depths alongside the terminal and gantry cranes that could handle more than 20 across. However, since the need was imminent, at a very minimum the Port needed to be able to handle ships over 10,000 TEUs.

Massport and the State understood the seriousness of the situation and put the wheels in motion for a massive terminal overhaul.

The resulting reinvention of Conley Terminal and the channels began in 2014 and was an expensive undertaking with Massport investing $850 million in waterside and landside infrastructure and another $350 million for The Boston Harbor Dredging Project – a $350 million partnership between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and Massport.

The terminal improvements included a 50-foot deep berth alongside and three new ship-to-shore gantry cranes. The gantry cranes had to be specially designed to avoid air draft restrictions from Logan International Airport, located on the opposite side of the harbor from Conley Terminal. This made the cranes 205 feet high from sea level and 160 feet high from the rail, with an outreach of 22 rows, capable of handling 12,000-14,000 TEU vessels. Other improvements included a new gate in the processing area and new reefer stack.

Phase 2 of the dredging was completed this year, which from a dredged material perspective represents 90% of the task. Phase 2 resulted in deepening the Outer Harbor Channel, from 40 feet to 51 feet; the Main Shipping Channel, from 40 feet to 47 feet; and the Reserve Channel, where Conley Container Terminal is located, from 40 feet to 47 feet. It is also worth noting that Boston Harbor has a 9-foot plus tidal variation, which enables larger ships to come in on the high tide and unload and depart on a low tide. Additionally, the Turning Basin was widened to 1,725 feet enabling the Port to handle 10,000 TEU ships and larger.

$61.8 million of the federally funded Phase 3 segment was awarded to Great Lakes Dredge and Dock in March. This final phase of the Boston harbor deepening project involves the excavation through drilling and blasting of hard rock and will significantly improve access to Conley Terminal. The project is expected to be complete by the end of the year (2021) and is not expected to impede container terminal traffic during the process.

The two gantry cranes scheduled for newly built Berth 10, which are being built in China, are expected to be finished by April. The cranes will be shipped on a 2 ½ month voyage to Boston and should arrive late June. After that the process of getting the cranes ready and tested for operation and labor trained should put the Berth on pace to begin operations sometime in late September.

Can Conley be a 400,000 TEU Terminal…or More

The need to overhaul the terminal and channels for bigger boxships was driven home when South Korean Hyundai Merchant Marine (HMM) joined THE Alliance (THEA) composed of the carriers Hapag Lloyd, ONE, Yang Ming and HMM which was calling in Boston. HMM was adding their 13,000 TEU ships to the rotation calling in Boston – a size the Port and Conley Terminal weren’t prepared to handle. As a result, THEA canceled their weekly Boston call which amounted to nearly 30%-33% of the cargo volumes handled by the Port. This left the 2M alliance comprised of Maersk and MSC (Mediterranean Shipping Company) and the Ocean Alliance [composed of CMA-CGM, APL, COSCO, Evergreen and OOCL] to pick up the slack. Since the number of slots on rotation is allocated on a port-by-port basis, soliciting more slots for one port is taking away slots from another port. Thus, trying to convince the other alliance member carriers to shift more slots to the Boston call was virtually impossible.

Nonetheless, around 66% of the TEUs “lost” when the THEA pulled out were made up by an increase in TEUs handled by the 2M and Ocean carrier alliances. The result was a “good” bad year with over 282,000 TEUs passing over the piers.

But the real question is can Massport regain the momentum it had established in the years prior to the 2020 pandemic and surpass 400,000 TEUs?

When the new berth is fully operational sometime in the Fall of 2021, Massport will finally have the tool in the tool box to solicit new services and bigger ships. Obviously, getting THEA back into the fold is a priority. Another key is upgrading the 2M service to larger vessels from the current 4,500 TEU ships. Finally, on the Massport wish list is a Suez Canal service that would offer the Port connections to the Mediterranean, India and the Sub-Continent and Asia.

Will They Come?

Just because you built it, will they come? The answer is a little more complex as the Port is bracketed by the Port of Montreal to the north, the Port of Halifax to the northeast and the mega-Port of New York/New Jersey to the southwest. And this doesn’t include the competition from ports down as far as Baltimore for slots on containership services. So, ocean carriers have choices. In fact, by most estimates the Port of New York/New Jersey is the “largest” New England port with a 50% share compared to a 45% slice for the Port of Boston and the remaining 5% divided up among services through Canada, up the East Coast from other ports and rail from the West Coast ports.

From a demand perspective, Boston handles far more inbound cargo than outbound. For example, in FY2020 Boston handled 143,665 import TEUs compared to 75,120 export TEUs with another 62,276 TEUs of empties. In terms of ratios, for full containers inbound it is about 50.8% to outbound 26.5% (the rest are empties). Historically, inbound containers are full of higher value consumer goods that cube out – basically lighter freight – while export containers generally “weigh out” as they are full of scrap or other heavy low value commodities.

This disproportion of inbound to outbound isn’t unique to Boston – the West Coast has the same issue – but it is a conundrum for ocean carriers trying to balance both revenue potential and boxes. They need exports to fill containers for the return – a repositioning of the boxes but to areas with high value export freight. The inherent advantage that Boston has is the regional market’s robust demand for high value goods and the relatively small geographical size of the consuming region means empties remain close to exit points. Finally, the location also favors less congestion and velocity to and from regional markets.

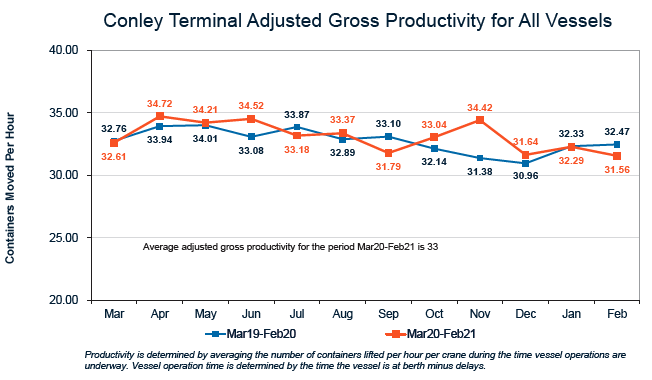

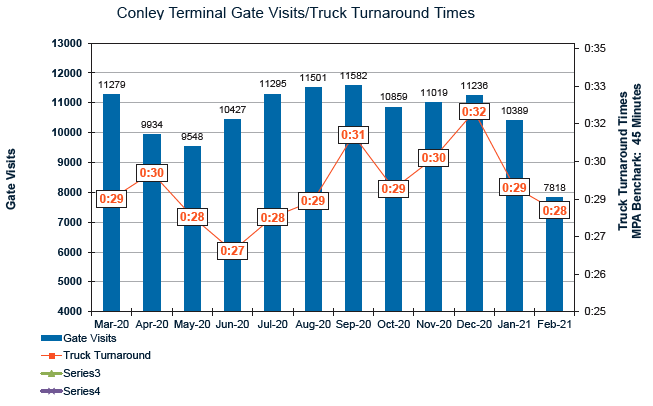

The Port has been very successful in improving efficiencies as gantry crane container moves per hour (gmph) average 28 gmph and are rising while truck turns are largely under 30 minutes. (see chart on page 8) Remarkably, during the pandemic the ILA didn’t suffer any loss of labor due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

So, will the ocean carriers increase the size of their ships and push the Port over the 400,000 barrier? With the infrastructure and commercial moves Massport has made over the past decade, it is hard to see it not happening.