Washington’s re-imposing of sanctions on Iran has businesses confused with what constitutes a violation. Particularly, hard hit is the petroleum industry and the related project sector.

Washington turned Iran-related global trade and shipping on its head after the Trump administration in May withdrew from the multilateral nuclear agreement with Iran and began to re-impose harsh sanctions on the Mideast nation and those doing business with it. At the top of the list is the petroleum industry and related projects. But what is really worrying the industry is the “secondary sanctions.”

Washington’s attempts to punish Iran aren’t limited to targeting just that country’s businesses. Under so-called “secondary sanctions,” foreign entities that support an embargoed country are cut off from doing business with the U.S. and with American banks.

To clamp down on Iran, Washington now prohibits the Iranian government from acquiring US dollars. It will soon ban financial institutions from doing business with Iranian banks.

“Any kind of steps taken to evade or avoid US sanctions is itself considered a violation of sanctions,” explained Daniel Pilarski, a New York-based partner with Watson Farley & Williams, who heads the law firm’s US sanctions practice. “Any facilitation by a US person of trade with Iran could also be a violation of US sanctions. That’s the reason why trade in dollars is prohibited.”

Some of the sanctions took effect in August, with the rest in November.

Just what Iran will do to survive remains an open question. There is continued confusion about everything from rules governing non-embargoed trade and potential exemptions to the status of Iranian ports and the European Commission’s efforts at countering American punishment. The EU remains committed to the multilateral agreement, officially termed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

A high level of uncertainty and anxiety has already caused major container shipping lines to err on the side of caution. Maersk, CSM, Hyundai Marine and CMA CGM have all announced they will no longer do business with Iran, even if some of the goods they carry aren’t on Washington’s prohibition list.

Difficulties

“There is a very strong argument that they could, if they wish, continue to trade with Iran,” said Pilarski. “They’ve decided that the costs and the risks that are so great, it’s just not worth it for them.”

“It’s very difficult,” added Woolich. “From a practical point of view, there’s a whole problem of making payments to Iran, finding a bank that will process payments.”

There are some openings for Iran-related trade, although it’s difficult to believe many shippers and ships will take advantage of these. Washington clarified an initial embargo on Iranian ports by saying that “ordinary course, normal transactions that are necessary to effect maritime trade with Iran in non-sanctioned goods should not be subject to US secondary sanctions,” explained Pilarski.

That includes basic port dues, handling charges and docking fees.

However, significant transactions with Iranian ports, as well as shipbuilding, remain prohibited. That includes the sale of any equipment or technology.

In addition, Pilarski said, “there’s a danger in dealing with” Iranian port operators outside of Iran.

Washington specifically names one port operator in its sanctions list. Tidewater Middle East Co., allegedly owned in part by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, claims to be the largest container port operator in Iran.

“You are going to see a lot of insurance companies and P&I clubs stepping back with trading with Iran,” said Pilarski.

British Marine, for example, issued this cautionary note in July: “We will be undertaking the full due diligence of Iranian parties on a case by case basis, in order to assess the risk/claim for potential exposure to sanctions. New and existing policies will be reviewed with caution. In addition to adequate due diligence we would expect there to be an adequate sanctions exclusions clause on risk.”

Washington has threatened any company that breaks the embargo with so-called “secondary sanctions,” which means being banned from doing business in the US or with Americans. Even those who don’t have business ties with the US risk pariah status, officially termed a “specially designated national,” or SDN. This is the same designation as a terrorist or drug dealer. “What that means is anyone who does any sort of background check on you or your company, there’s going to be a giant red flag,” said Pilarski. Such a list has an extremely far reach for even those who have no direct contact with the US. “It’s less what the US does with you and more what everyone else does to you,” said Pilarski. “Suddenly anyone who doesn’t want to deal with SDNs will want to avoid you.”

During the last period of sanctions against Iran, the US government came down hard and levied heavy fines on some European financial institutions that breached sanctions with Iran. Washington also has put companies on a sanctions blacklist including an Israeli company whose Singaporean subsidy that sold a tanker to the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines.

In an effort to assert its sovereignty and maintain the integrity of the multilateral agreement, the European Commission issued what’s called a blocking statute. This forbids EU companies from complying with the sanctions and offers redress for US sanctions applied outside its own borders.

European companies face two major issues with this kind of blocking statute, explained Woolich. One is that it only works under EU law. “If you have assets or business in the US, compliance with the EU blocking statute won’t protect you from any non-compliance with US sanctions as a matter of law, and European companies know that the US government enforces its sanctions,” he said. The second problem is that in the past, the EU blocking statute hasn’t been strongly enforced even in Europe. “So most companies caught between a rock and hard place would tend to abide by the US sanctions,” Woolich said.

Financial institutions, however, could find themselves in some legal jeopardy. For example, a European lender is financing a ship. The lender attempts to protect itself from US sanctions by inserting language in the loan document saying the ship can’t trade with Iran. “The borrower might turn around after the agreement and say ‘that’s unenforceable. I can trade with Iran if I want to and if you attempt to stop me, I’ll go to the European Commission and say that you’ve harmed me,” said Pilarski.

Petroleum Industry Projects

Fundamental to Iran’s future is the fate of its oil industry. At the very least, Iran must reorder its oil exports away from Western Europe and more toward Russia and China, when petroleum-related sanctions go into effect in November.

“They’ll have to find a workaround,” said Vanand Meliksetian, an energy and utilities consultant with Sia Partners, based in Amsterdam.

General business with Iran is already slowing to a crawl. The next big casualty of the embargo will be oil destined for Western Europe. “Oil tankers to Europe will be reduced almost to zero,” said Meliksetian.

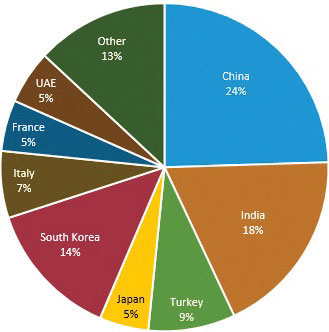

Last year, Iran exported 2.1 million barrels a day, or about 777 million barrels, ranking it fifth in the world. Some 38% of this went to Europe.

Iran had begun to rebuild its oil trade with Europe in 2016, after Iran, the US and Europe signed an agreement that would freeze Iran’s nuclear weapons capabilities in return for the lifting of some sanctions. This was termed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Although the US didn’t lift sanctions, abiding by the agreement, Washington waived them for successive six-month periods and revoked executive orders that had imposed additional sanctions.

South Korea, Japan and India each are asking for exemptions from Washington, by showing that they’re reducing imports from pre-sanctions levels. According to Reuters, Indian refiners plan to cut in half their imports this month and next to demonstrate its willingness to reduce consumption.

The Trump administration has yet to indicate it’s at all willing to exempt these countries, however. A Bloomberg story recently said Washington was playing hardball with Tokyo and demanding Japan completely stop oil imports from Iran.

“We will consider waivers where appropriate,” US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo said at a press briefing earlier this month in New Delhi, according to Bloomberg. “It is our expectation that the purchases of Iranian crude oil will go to zero from every country or sanctions will be imposed.”

Russia-China Connection

China and Russia become keys to Iran’s future. There’s reason to believe that, even at the risk of incurring additional wrath from Trump, China may step up importation of Iranian oil, while Russia boosts its oil imports. It’s geopolitics at its messiest.

Defying the US could also make economic sense to both China and Russia. “If Iran doesn’t have many options, it will go to great lengths to get its oil sold, which means big discounts,” said Meliksetian. “When you’re a very big importer of hundreds of thousands of barrels per day, those discounts can go into the millions. That’s a very big plus for Russia and China.”

China is especially important. If China “buys Iran’s oil, we can resist the US,” one unnamed Iranian economic analyst told the Financial Times in July. “China is the only country which can tell the US off.”

Meliksetian, for one, believes that China will, indeed, attempt to import more Iranian oil and for a variety of reasons, in addition to the big discounts it can garner. First, China sees an opportunity to get more involved in Iran’s energy industry and with Iranian infrastructure as a whole, with Chinese companies supplanting Western ones. Second, China will denominate its purchases in Yuan, bolstering efforts to wean oil trade away from petrodollars and toward the Chinese currency. Third is China’s own trade dispute with Trump. This is one way to subvert Washington policy.

“The Chinese will continue supporting Iran as it is increasingly dependent on China,” said Meliksetian, who added that China will likely use companies that have no direct exposure to the US and American business. That’s true for both shipping and insurance.

Russia isn’t so straightforward.

Russia, of course, has forged a political alliance with Iran, in part to bolster its influence in the Mideast. Last year, the two agreed on a barter deal, worth about $40 billion, in which Russia would import some 100,000 b/d and pay half in Euros, half in goods, including basic commodities like wheat and machinery. Then, in July, an Iranian official announced that Russia would invest some $50 billion in Iran’s oil and gas industry.

Why would Russia, one of the world’s biggest oil exporters, help an oil-producing competitor? One answer is that it could get the oil cheap and make a profit off the reselling. Another is that Russia could better influence the global petroleum market.

“Russia will on a smaller scale become an energy hub for Iranian oil, but that’s on the economic side,” said Meliksetian. “On the political side, the Iranians will be more dependent on the Russians. The Russians strategic position in the Middle East will only be strengthened by this move.”

_-_127500_-_3c040b6cb8335b4cad39477f7f55a34202568c96_lqip.png)