The bottom line is that the traditional Atlantic allies are working together again on common interests.

From a trade perspective, the deal that the Biden administration reached on steel and aluminum tariffs with the European Union generated more ambiguity than clarity. The agreement rolled back tariffs on both sides, ostensibly striking a blow for freer trade. But the deal includes more protectionist than free-trade elements, which is why U.S. tariff advocates were more effusive about the deal than free traders.

The EU deal, announced on October 31, partially resolves a trade war started by former President Donald Trump, whose administration imposed, in 2018, a 25% tariff on steel and a 10% tariff on aluminum imported from the EU, on the basis that these were national security threats. EU exports to the U.S. subject to these Section 232 measures declined from 5.1 million tons in 2018 to 2.4 million tons in 2020. In response, the EU imposed “rebalancing measures,” hitting $3.2 billion in United States exports—including steel, aluminum, bourbon, motorboats, motorcycles, blue jeans, corn, and peanut butter—with retaliatory tariffs.

Under the agreement, which will go into effect January 1, the Section 232 tariffs remain in place, but the U.S. will allow $5.5 billion of EU steel and $1.2 billion of EU aluminum exports to come in tariff free. That translates to around 3.3 million tons of steel coming in under quota, 1.7 million tons less than was imported before the Trump tariffs, and 384,000 tons of aluminum.

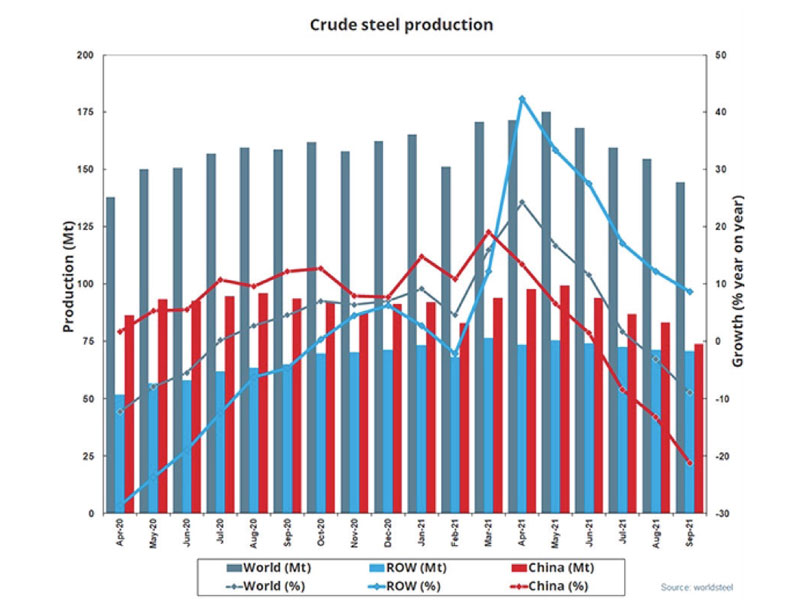

Pushback on China Steel Exports

Supporters of the agreement saw it as pushback against cheap steel from China and protection for American jobs. Kevin Dempsey, the president and CEO of the American Iron and Steel Institute, an interest group representing the domestic industry, hopes that the deal represents the beginning of “a common action plan for challenging” China’s industrial policies and steel overcapacity.

Tom Conway, the president of United Steelworkers International, also supported the deal because it caps duty-free imports. “The deal creates certainty for domestic producers of steel and users who are unable to find domestic supplies,” he said. That’s true as long as the quota is enough to satisfy domestic demand for EU imports, which is debatable.

But Richard Chriss, president of the American Metals Supply Chain Institute, criticized the deal for not withdrawing the administration’s national security threat determination for EU steel imports. He also slammed the EU for implicitly accepting “the U.S. determination that EU steel in some quantities continues to be a threat to U.S. national security.” The deal, he concluded, “leaves in place a regime that has raised the cost of steel used in the construction industry, in consumer goods, and in energy production.”

Likewise, the Coalition of American Metal Manufacturers and Users (CAMMU) expressed disappointment “that the agreement will not completely terminate these unnecessary trade restrictions on our allies.” The organization anticipates that the bipartisan infrastructure bill, which was signed into law November 15, will stimulate a “surge in steel and aluminum demand,” and implied that the quota may not be enough to satisfy demand for European imports. “The threat of tariff reinstatement looms,” said a CAMMU statement. (For an analysis of how the infrastructure bill will impact aluminum, see Bipartisan infrastructure bill – good for aluminum)

The tariff deal is one reason why the 2022 steel outlook is murky for the South Jersey Port Corporation (SJPC), whose terminals handled 1.9 million tons of breakbulk steel through October, a 118% increase over last year. “Some people are bullish because the tariffs are being removed,” said Brendan Dugan, SJPC’s assistant executive director. “But it’s difficult to say what the future holds because of the potential downside in the imposition of quotas.”

EU-US: Politics Trumps Trade…For Now

Jake Sullivan, President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, on a press call, said the deal would transform the U.S.-EU relationship “into a joint forward progress on two central challenges”—“the threat of climate change and the economic threat posed by unfair competition by China.” The agreement negotiated “a carbon-based arrangement on steel and aluminum trade,” Sullivan said, that “addresses both Chinese overproduction and carbon intensity in the steel and aluminum sector.” Sullivan was referring to the “melted-and-poured” standard for EU steel to qualify for the quota, which would prevent Chinese steel from being passed off as an EU product.

Sullivan’s take shows the agreement was more about advancing political goals than enhancing trade. A common U.S.-EU agenda has been unraveling for some years, beginning during the Obama administration, when politics scuttled the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Former President Donald Trump had no interest advancing the relationship, instead provoking trade wars and dismantling the World Trade Organization’s dispute resolution mechanisms.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and President Joe Biden share an agenda to rebuild transatlantic cooperation on climate policy, technology, supply-chain resilience, and human rights. Brussels, encouraged by Biden’s campaign pledge to “work with allies,” offered a blueprint for transatlantic trade and technology cooperation that signaled an alignment with Washington’s concerns over China. That advancement suffered a hiccup when the commission later announced a bilateral investment agreement with Beijing, but the newly-launched U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council and a September U.S.-EU summit in Pittsburgh served as a course correction to that misstep.

The U.S. and the EU still have their differences when it comes to these issues. The EU wants to tackle climate policy with carbon taxation, a difficult policy for the U.S. to pull off. On China, Brussels is concerned that Biden’s policies are a continuation of Trump’s, under a different guise, while Washington wonders whether the EU takes the threat posed by China seriously enough.

Taken as a whole, the October 31 agreement represents a first step toward repairing the transatlantic relationship and advancing common interests. As a trade agreement, it doesn’t go very far, but, despite that drawback, leaders on both sides of the Atlantic are no doubt breathing a sigh of relief that these traditional allies are working together again, making the agreement more significant as a political, than a trade, document