In the past twelve months, prices for lumber and forest products hit a historic high and then pricing crashed. What’s next?

It was Bunyansque, for over a year lumber prices rose like…well, like a redwood tree and then crashed, as if Bangor, Maine’s own Paul Bunyan had yelled timber. What happened?

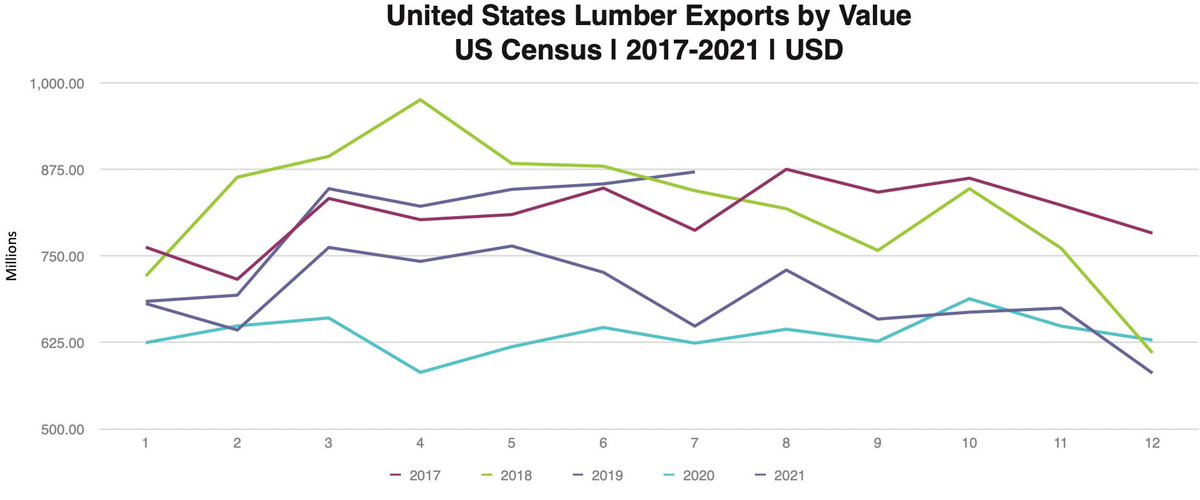

It’s not surprising that the U.S. is the world’s largest lumber market. However, even with a vast inventory of domestic forest to supply lumber and related products, the U.S. is also the world’s largest importer of lumber. Imported lumber generally accounts for 30% of the U.S. consumption in any given year. And with the vast resources of lumber-producing Canada next door as a near-shore supplier, the U.S. has relied on its northern neighbor to fill in a large portion of the gap – particularly in softwoods – between domestic production and consumption. Descartes-Datamyne (a company that tracks U.S. imports and exports) data on U.S. lumber imports and exports (see charts) observed that the “U.S, dwarfs other top countries as primary destination country for Canadian exports.” But also noted that the “Top countries of destination for U.S. lumber are China (1) and Canada (2),” illustrating the complexity of the lumber industry in North America.

And when it comes to lumber, the relations between the U.S. and Canada aren’t good. Lumber sales from Canada to the U.S. have been trending downward for the past five years.

Of course, forest product trade between the U.S. and Canada doesn’t exist in a vacuum. There are many other economic forces influencing trade trends. Taken together, the trade in forest products is a complex weave of suppliers and producers that can change on a moment’s notice.

Naturally, China – as the Descartes-Datamyne data points out – figures prominently into the mix as a largely raw material importer and forest product exporter. And there are other exporters like Russia, and the Scandinavian countries, Southeast Asian producers like Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia, along with countries like New Zealand, Australia and the European, African and South American nations – the latter two often supplying exotic woods.

Oh Canada, Redux

The U.S. and Canada have for nearly four decades been embroiled in a lumber dispute (see AJOT issue 712, published 9/29/20, “Misery Whip” for a more detailed account). And a succession of administrations on both sides of the border have failed to find common ground for an agreement. After the last Canadian-American lumber agreement expired in 2015, a “new” round of talks began in 2017. In the meantime, the U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) levied countervailing duties on Canadian softwood lumber imports, arguing Canada’s lumber industry is unfairly subsidized by the Canadian government, as most of Canada’s lumber comes from publicly-owned forests, as opposed to the predominately private operations in the US. The U.S. contends the “stumpage fees” that lumber companies pay to cut trees on public land (generally provincially held) public land is levied at below-market rates and thus constitutes a “subsidy”.

As a result, Canadian lumber exporters have reportedly paid close to $3.9 billion in duties to the U.S.

During the Trump administration the lumber dispute was taken before the WTO’s three-person panel. In August 2020 the panel determined that the countervailing duties designed to offset Canadian subsidies were illegal as the U.S. had not shown that the prices paid by Canadian lumber companies for timber on government-property was artificially low compared to the market and caused “material injury” to US lumber companies.

The Trump administration felt that the WTO decision wasn’t fair to the U.S. The then US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said of the panel’s decision, “This flawed report confirms what the United States has been saying for years: the WTO dispute settlement system is being used to shield nonmarket practices and harm U.S. interests.”

Once Again, Stumped By “Stumpage”

With that legacy, the lumber dispute was inherited by the Biden Administration to resolve.

Canada has said it wants a new agreement. Canada has also said it wants its money back collected from duties. And Canada felt it had leverage with the soaring prices of softwood lumber and soaring demand in the U.S. But that was back in June 2021 at the G-7 Summit meeting when lumber was at a record high.

Unsurprisingly, the Biden Administration, like the Trump administration before it, didn’t see it that way back in June and the crash in lumber prices hasn’t helped Canada’s position.

In May, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo reportedly said she wants to find a “long-term solution” to the lumber dispute. But the Biden Administration, just as the Trump Administration, is unwilling to move without Canada addressing the “stumpage” issue.

In fact, the U.S. Court of International Trade (CIT) eliminated a rule that allowed foreign companies such as Canadian lumber producers to have individual tariff rates lowered.

The rule allowed foreign producers to quickly apply for lower countervailing duty rates if they weren’t individually investigated by the DOC in its original duty inquiry. With the August 18th CIT ruling, some Canadian lumber companies could have higher duties reinstated, although it will apply only “prospectively” [with consideration for the future].

There has been some indications – however slight – of movement in the four decade old logjam. Nearly a year ago, the DOC imposed countervailing duties of around 9% on certain Canadian lumber exporters, down from just over 20%. But little that has happened since points to a quick (or otherwise) resolution of the longstanding dispute. The Biden Administration has holistic desire to improve relations with long-term allies, such as Canada. The Trudeau administration would also like to see relations with its powerful neighbor to the south improve after getting the cold shoulder from the Trump administration.

But with forces on both sides dug in, finding common ground is difficult. From the Canadian perspective refunding the $3.9 billion in duties is important. After all, the WTO panel found in their favor. And way back in 2006 the George W. Bush administration did refund $4.4 billion of $5.4 billion in collected countervailing duties on the very same issue. However, finding a way to determine what is a “fair” commercial price for lumber sold to the U.S. harvested from public land in Canada, is a sticking point from the U.S. perspective. Can the pricing for softwood lumber harvested on public lands be indexed? Possibly. But there is little inclination for compromise in Canada for a pricing model already deemed “fair” and this stumps negotiators on both sides.

If a Tree Falls in the Woods…it Reverberates Around the World

There is an old philosophical query, “If a tree falls in the woods and no one hears it, is it real?” Philosophy aside, in the real world of economics, when a tree falls, the entire interwoven gigantic global eco-system of forest product suppliers and consumers knows about it. For example, as Descartes-Datamyne data on U.S. lumber imports and exports indicates (see charts) the “US dwarfs other top countries as primary destination country for Canadian exports” and the “Top countries of destination for US lumber are China (1) and Canada (2).”

For that reason, the recent crash in lumber prices isn’t just about the U.S. and Canada: It is the domino effect that one region or event like the COVID-19 pandemic has on another.

Take Australia. Australian lumber exports aren’t on the scale of the big suppliers like Canada, Sweden, Russia, the U.S., Finland or Germany (sawn wood) but up until recently held an important place as a niche supplier to China – with the PRC accounting for nearly 90% of the country’s log exports (largely used for pulp) worth $1.23 billion.

In December of 2020, China abruptly stopped log shipments from New South Wales and Western Australia after reportedly finding “live forest pests” in the imported wood. While there is considerable disbelief on the Australian side that any live “pests” were actually in the wood, the Chinese refused to lift the restrictions – essentially banning lumber exports, similar to blocks on other commodities like lobster, beef, and cotton. With the recent announcement by Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s government to acquire U.S. nuclear powered submarines as part of Australia-U.S.-UK tripartite alliance, which angered China’s President Xi Jinping, Australian lumber exports are likely to continue to be invested by “live pests” for the foreseeable future.

So, where does Australia go now and conversely where does China look to replace the Down Under volume?

Australia is looking to export to other destinations like India, South Korea or Taiwan but none of the alternatives are likely to fully replace the volumes China imported.

Conversely, China has had no problem replacing the banned Australian import volumes the global forest product marketplace. There were plenty of sourcing nations – even including the U.S. and Canada – ready to fill the gap. And neighboring New Zealand, in the absence of Australia is setting records with their sales to China.

But as Australia’s imbroglio with China illustrates, the global lumber marketplace is running topsy-turvy with little indication that it will settle soon. For example, Russia has a pending export ban on logs due to come into force in January of 2022 – a ban reaffirmed last May – which could dramatically shift purchasing for its largest customer, China.

Will China make more upstream purchases from Russian lumber producers (it happened before with similar export ban on birch that pushed buyers from log purchases to product purchases) or look to other suppliers, such as Canada or New Zealand to make up the difference? Either way, there will be an impact on global lumber suppliers.

Timber – The Collapse and Possible Rebound in Lumber Prices

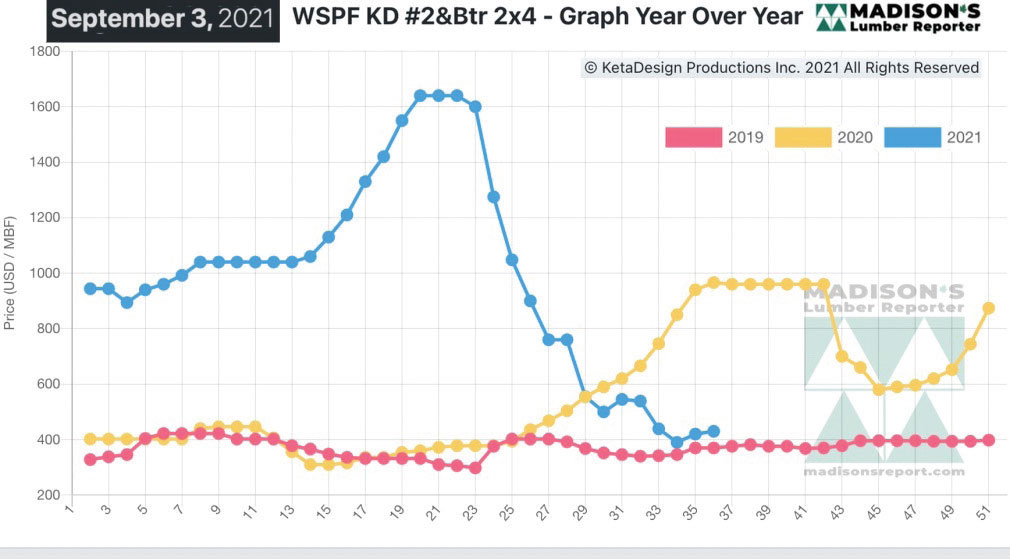

Roots of a price climb. Starting back in April of 2020, forest products, especially lumber prices have been climbing – pulled along as a portion of the wide-ranging post-pandemic upward movement of commodity prices. By August of 2020 lumber prices had reached pre-pandemic levels before again slumping. Then it really began – lumber prices in the U.S. simply took off like a SpaceX Falcon rocket. By May lumber prices had hit an all-time high of $1,670 mbft (thousand board feet), compared to around $345 mbft in May 2020. (see Madison Lumber Reporter chart below for pricing by weeks).

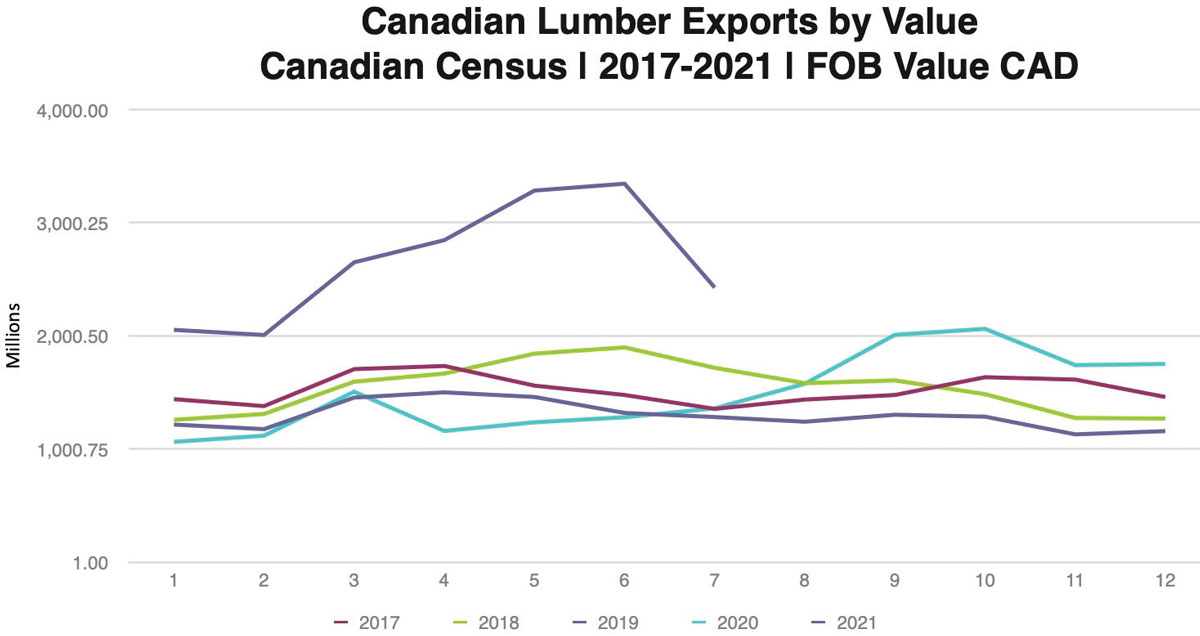

There were a myriad of reasons for the sharp rise in U.S. lumber prices. Although DIY (Do-It-Yourself) demand was strong coming out of COVID-19 lockdowns, the extent of the housing rebound was an unexpected push to demand for framing lumber. Wildfires in the west of both Canada and the U.S. also impacted supplies to sawmills as did hurricanes and other metrological events. In addition, a strained supply chain both in North America and abroad slowed deliveries to a crawl. Lumber supplies from Canada (see Descartes-Datamyne Canada Export chart) were also down, partly because of the aforementioned lumber dispute but also the effects of the mountain pine beetle in British Columbia.

The cumulative upshot was a dramatic rise in lumber prices. In April, near the peak of the lumber price spike, the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) estimated that the rise added as much as $36,000 to the cost of a new single-family home. And concern over building costs were climbing the political ladder in DC, because as construction slowed, so did U.S. employment and hopes for a recovery from the pandemic. Pressure to make a deal with Canada mounted (see above) to relieve the price surge with more additional lumber sourcing, despite pressure in the opposite direction from the U.S. Lumber Coalition, a group composed largely of U.S. softwood lumber producers.

But by July, everything had changed. Lumber prices were in a free fall as if Paul Bunyan himself had yelled timber. The Madison Lumber Reporter, one of the best covering the industry, wrote in their September 3 newsletter, “Construction projects which had been put on hold roared back to life as builders rushed to complete them before winter starts. Most players agreed prices had generally hit bottom, though the real proof will come post-Labor Day.”

Wood Resources International, in their WRI Market Insights 2021 (3rd quarter) wrote in their analysis of the rise and fall of lumber prices, “Canadian lumber prices have spiked similar to U.S. prices through 2021, with a record high in May followed by sharp declines during June through August.” Adding, “Due to the strong U.S. lumber market, Canada and the U.S. reduced lumber exports overseas in the first half of 2021.”

In the Descartes-Datamyne data [Descartes-Datamyne is one the best companies at tracking ocean U.S. imports and exports] lumber charts show an increase in dollar value in June and July figures, supporting the lower prices and easing of supplies.

But at this writing, lumber prices have begun creeping up and inventory has been pared back and supply side lag times are lengthening.

And perhaps the more unsettling is the potential disruptions from the Delta variant. The U.S. has already seen what the COVID-19 pandemic can do to create labor shortages in industries. Should the Delta variant cause sustained major disruptions to U.S. sawmill production, where will the U. S. consumers go for lumber and at what price? Particularly, if the Delta variant begins squeezing supplies and processing capabilities in other high profile consuming countries, such as China, Japan, India or Europe. Under such a scenario a shortage in supplies could trigger another steep climb in lumber prices, similar to the one that occurred in 2020.