International pressures may motivate the President to act. But engaging China is a nagging issue.

The Biden administration has reversed many Trump-era policies, but has dragged its feet on rescinding the tariffs on steel and aluminum imports the former president imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Under that provision, the former president justified the levies with a finding that the imports posed a threat to national security.

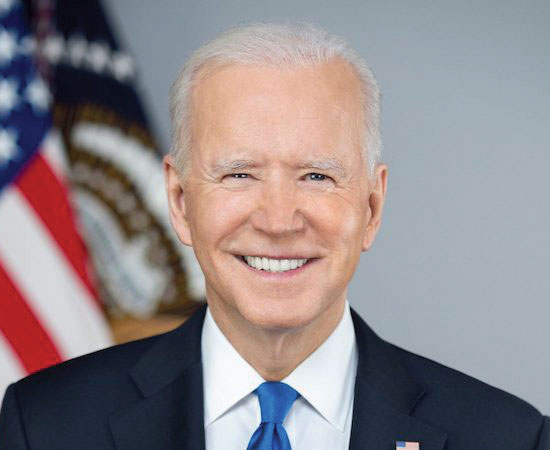

Since his inauguration, Biden has re-imposed the Section 232 tariffs on aluminum products from the United Arab Emirates that Trump lifted in the last days of his administration, not a good sign for those hoping for a change of direction. The White House did announce, however, that the Trump tariff regime is under review.

Fans of the Section 232 measures, like the Economic Policy Institute, in a recent report, say they “improved industry conditions, spurred investments, and directly created 3,200 new steelmaking jobs.” The EPI also claimed that “the measures helped curb U.S. steel imports by 27% by 2019 with no meaningful real-world impact on the prices of steel-consuming products, such as motor vehicles.”

The Debate Renewed

Those claims are subject to dispute, just as the notion that they were appropriate under national security standards was dubious. Opponents of the tariffs say the tariffs hurt U.S. manufacturers that use steel and aluminum in their production and open up opportunities for corruption in the messy exclusions process. And, as noted by Simon Lester, associate director of the Cato Institute’s trade policy center, “they inflame tensions with close allies by pushing the boundaries of what is permissible” under the aegis of national security.

Data show that steel prices increased following the implementation of the Section 232 tariffs. An index of hot-rolled coil prices in the U.S. found they spiked to $916.80 per ton in June 2018, a 10-year high at the time. As of April 12, the index stood at an all-time high of $1,355.00 per ton.

Those price increases have caused damage to equipment manufacturers across the U.S., according to Dennis Slater, president of the Association of Equipment Manufacturers. The “tariffs on steel and aluminum have significantly raised the production costs for equipment manufacturers,” he noted.

A recent Reuters report indicated that “steel is in short supply in the United States and prices are surging. Unfilled orders for steel in the last quarter were at the highest level in five years, while inventories were near a 3-1/2-year low.”

As far as jobs go, the Coalition of American Metal Manufacturers and Users, in a recent letter to President Biden, stated that “the Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs have damaged U.S. consuming industries that employ more than 6.8 million workers, compared to 140,000 in the U.S. steel industry.” According to a study by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the tariffs cost 75,000 U.S. manufacturing jobs.

The tariffs have generated some other perverse results. The Aluminum Association noted recently that “the current Section 232 product exclusion process has inadvertently made the United States a magnet for imports.” For example, the Commerce Department granted 8.3 billion pounds of aluminum can sheet exclusions in 2020, more than twice the size of the entire annual U.S. market. “If importers were to fully utilize the exclusions already granted by the Commerce Department,” an association report said, “those customers would not need to purchase one pound of American-made aluminum can sheet for the next two years.”

A Complex Issue

The American Iron and Steel Institute, which represents many domestic steelmakers, supports maintaining the Section 232 tariffs. AISI interim CEO Kevin Dempsey noted there are indications of increased steelmaking capacity in China, and with it, the possibility of an increased capacity-production gap that narrowed between 2016 and 2019. “We’re very lucky that we have not seen a new surge in imports in the wake of COVID-19 as we recover from the shock this year,” Dempsey said, “and I think that is due in part to the steel tariffs being in place.”

But not all U.S. steel makers are on board with the tariffs. Tamara Lundgren, CEO of Schnitzer Steel Industries, Inc., a recycled steel manufacturer based in Portland, Oregon, allowed that the Section 232 tariffs gave the domestic industry “a boost,” but added that “a climate defined by retaliatory threats creates a climate of uncertainty.” Across-the-board tariffs, she argued, are “an inadequate long-term solution,” and represent “a blunt-force response to a far more complex problem,” namely, excess steel production capacity in China. (See sidebar on page 12)

Ultimately, tariffs reform may be pushed along by both domestic and international political considerations. In mid-March a bipartisan group of senators introduced the Trade Security Act, which would amend Section 232 by requiring the Department of Defense to justify the national security basis for new tariffs and increasing congressional oversight of the process.

On the international front, the European Union is set to increase the duties on an array of U.S. imports ranging from steel to whiskey from 25% to 50% on June 1, unless the U.S. rescinds the Section 232 tariffs on imports from the EU. European leaders are especially enraged because the Section 232 tariffs were imposed on national security grounds. Given the president’s foreign policy background and his emphasis on the importance of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the administration may be eager to seek an accommodation.

Some experts expect that to come in the form of a move from tariffs to quotas, as occurred with South Korea, Argentina, and Brazil in June 2018. But quotas represent yet another trade restriction and may not mollify EU leaders. There is also some talk of kicking the can down the road, with the U.S. and EU agreeing to suspend tariffs for six months as negotiations continue. Either way, a reckoning will eventually come, and time will tell whether President Biden makes good on his campaign message and his professed approach to trade and international relations.