There is a major wind power building spree coming on ahead of the loss of federal development initiatives in 2020. The question is how will the project supply chain handle the boom?

Mammoth wind farms are expected to dot the plains of Oklahoma, the prairies of Wyoming and the scrublands of eastern New Mexico and Western Texas, generating thousands of megawatts of power from the beginning of the next decade. These mega-projects, which will provide low-cost, efficient power for millions of consumers, will cost developers billions of dollars. They constitute the largest wind power initiatives in North America ever.

“There will be a new normal in terms of annual growth,” said Luke Lewandowski, global research manager for the Chicago-based MAKE Consulting, which specializes in wind energy.

This transitory surge poses a dilemma to equipment providers and specialized logistics handlers alike: How do they gear up for an expected building spree knowing that it will most likely be short-lived?

What’s more, getting this power to those who need it isn’t simple. That’s because these projects are designed to move electricity from rural areas, where they’ll be generated, into the population centers hundreds of miles away.

First, there’s the cost: The construction of an extra-high voltage power line costs a bundle, north of $50 million per mile of transmission line, according to one estimate. The 350-mile transmission line that will link the Oklahoma wind farm with Tulsa and other cities to the east in Arkansas, Texas and Louisiana will cost $1.6 billion, for example. The line is 765-kilovolts, the highest capacity on the market today, offering maximum output with minimal transmission loss.

But to build these lines requires regulatory approval and since they often cross state lines, the process is long and fraught. Philip Howard, the chair of Common Good, a non-partisan bureaucratic reform coalition, cites one transmission line that links Wyoming wind farms with the Pacific Northwest. “The builder of the line had to get permission of every single county in Idaho over which the line went,” said Howard. “That’s absurd.”

American Electric Power, which will construct the line, has asked regulators for expedited approval, according to AEP spokesperson Melissa McHenry, who cites cost-savings for customers as well as the renewable nature of wind. “We’re hoping for sometime in the second half of this year,” she said. “We believe it’s a hard thing for regulators to say ‘no’ to.”

Mega Wind Power Projects

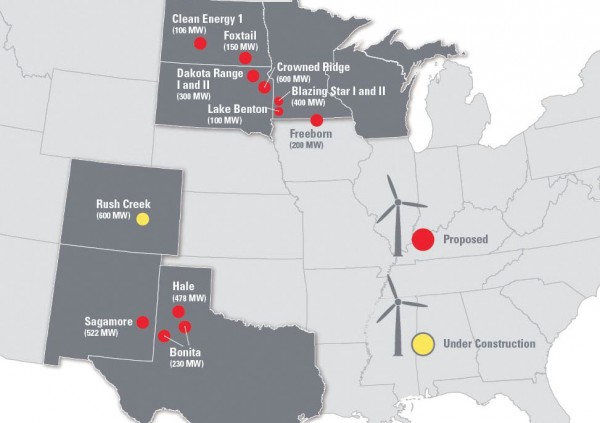

Invenergy is developing the 2,000MW Wind Catcher wind farm in the Oklahoma panhandle. The Power Company of Wyoming is undertaking the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project, which will produce up to 3,000MW of wind power. And Xcel Energy has plans for a 522MW farm in the prairie near Portales, New Mexico and a 478MW farm south of Plainview, Texas.

To put those in perspective, developers installed a total of about 8,000MW of wind power in the entire US annually in 2015 and again in 2016.

Propelling these are longstanding federal production tax credits, which Congress voted to end at the beginning of 2021. What’s more, the federal government will phase out another major incentive, the Energy Investment Tax Credit, by 2022.

Bigger projects using larger, more efficient wind turbines, offer cost advantages, but they don’t completely make up for the lost tax credits.

Both Invenergy and Power Company of Wyoming announced in 2016 that construction had begun. Under a sliding incentive scale, this construction schedule enables full tax credits, which will decrease over time until the end of 2020, when they are completely eliminated. Developers must complete a project within four years of construction starting. Xcel is waiting on regulatory approval, which the company has said could come this year. Developers have said that all these projects could come online by 2020.

Invenergy is furthest along in terms of awarding supply contracts. GE Renewable Energy will provide 800 turbines, each generating 2.5MW of power. Becky Norton, a GE spokesperson, confirmed that the blades will be manufactured in GE’s Little Rock, Arkansas plant, with the heads and hubs made in a GE facility in Pensacola, Florida. In addition, she said, “We plan to work with companies in Texas and Oklahoma to supply towers for the wind turbines. We’ll look at other components on a case-by-case basis with an eye towards leveraging suppliers in Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana given the logistical and other benefits in doing so.”

The Power Company of Wyoming has yet to award turbine and blade contracts, according to spokesperson Kara Choquette.

Getting regulatory approval for transmission lines on this project is no simple matter. A private company, TransWest LLC is developing the 730-mile route, which is designed to take the wind-generated electricity on a 600kv line from Wyoming to Nevada, near Las Vegas, servicing the desert cities of Nevada, California and Arizona. The project will cost an estimated $3 billion and will take three years to construct.

“With two-thirds of the rights-of-way secured through the federal permitting process on federal land, TransWest is now focused on addressing county permitting requirements, filing for the necessary State of Wyoming industrial siting permit, and acquiring easements for the state/private land,” said Choquette.

Vestas-American Wind Technology will provide the blades and turbines for the Xcel projects, the companies have said. At least some of these will be the latest generation 3.45 MW turbines, with blades that stretch just over 200 feet each. Vestas makes its blades in Colorado.

Mega-project Logistics for Wind Power

Just what this means to the onshore wind industry supply chain is a bit up-in-the-air. According to Lewandowski, “There’s an existing supply chain that could fulfill execution of these mega projects. The deployment of next generation wind technology may make it challenging to navigate through various states, because of weight or overhang restrictions, which could make an argument for local procurement. However, in order to complete projects within the current PTC window, it is likely that wind turbine OEMs will utilize proven technology with known logistics solutions,” he said.

Distance to site will certainly play a role in procurement, supply and logistics concerns of all these mega-projects. It’s not just the individual size of the latest-generation components, but the sheer number of turbines, blades and towers these projects require. They could create a logistics bottleneck, increasing logistics costs or cause smaller projects to scamper for equipment and transport.

“These mega projects are going to consume a lot of these resources, whether trucks, trailers, cranes, [or] crews that unload,” said Lewandowski. “A lot of activity is converging onto a two-year period, 2019 and 20, including new build and the repowering of existing wind power assets. From that standpoint, you might have more of a challenge as projects compete for resources.”

Yet, the fact that developers can’t insure these kinds of projects will continue into the 2020s means that manufacturers are reluctant to invest in new plants and logistics handlers are loathe to spend on state-of-the-art equipment. On the other hand, they may need bigger components to handle the newer generation blades and towers. It’s a tricky calculation.

“There might be some ramping up of hardware and equipment to support the 2019 and 2020 build,” said Lewandowski. “It’s not like that equipment won’t be used after the PTC phase down. It’s just that the older equipment might be phased out.”

Then, there’s the possibility of a revival of renewable energy incentives, if the Democrats take over government in 2020.

“Anything could happen to revive federal policy. States could also strengthen their policies,” said Lewandowski. “But it likely won’t be on the same scale,” he predicted, as current incentives.