Back in May, PCTCs (Pure Car Truck Carriers) full of cars lay idle off West Coast ports awaiting a chance to discharge their loads to ports already choc-a-block full of autos parked on piers. Nothing was moving as US demand for imported vehicles had all but dried up with stay at home orders and teetering paychecks. Equally, US based automakers cut production in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The unprecedented convergence of these pandemic driven events began really hitting home in the middle months of 2020 as auto sales plummeted to depths not seen in decades. But just as the pandemic has had an uneven impact on the health of nations around the world, so it has on the auto industry, complicating recovery scenarios.

Figuring Auto Demand in 2020

For example, a study published in August by global car carrier Wallenius Wilhelmsen appropriately entitled Market analysis: How the passenger car market is faring in 2020 and beyond [using IHS Markit data] reported a decline in global light vehicle sales from 23.2 million units in the 4th quarter of 2019 to 17.7 million in the 1st quarter of 2020 – a nearly 22% drop. And in an apples-to-apples comparison, when the 1st quarter of 2019 was compared to 1st quarter of 2020 the falloff was 22.3 million to 17.7 million respectively.

A report by automotive statistics provider “Goodcarbadcar” [using US Bureau of Economic analysis data] showed the dramatic impact of the pandemic on autos in the US as car sales in February were 1,434,716 units before dropping off a cliff to 912,800 units in March and an unbelievable 563,716 units in April. In comparison, in April of 2019, 1,355,548 cars were sold in the US. In light of these numbers, it isn’t surprising that the Wallenius Wilhelmsen report added, “Deep sea light vehicle volumes could decline from 14.9 million to 11.4 million in 2020 – a drop of 23% compared to 2019. This estimate may be further revised downward.”

And the Wallenius Wilhelmsen report ominously added, “Deep sea volumes could take until 2023 to recover to 2019 levels.”

Ti in their recently released study Automotive Logistics, A market in crisis observed, “In some respects, even more concerning to the sector has been the collapse in sales driven by the COVID-19 pandemic. This has disrupted both sales and production. The weakness of short-term cashflows has forced many VMs to seek finance from central banks… Such has been the destabilisation of VMs that governments have been working behind the scenes to arrange mergers …over the summer of 2020 the Japanese government was pressing for Nissan and Honda to arrange some sort of merger.”

Because of the global nature of the auto industry, the impacts on production varied. While the US was shuttering its production in the first quarter, automakers in countries like South Korea, Japan and China and in some cases Europe, were either emerging from the pandemic or had yet to feel the full impact.

Take the case of Hyundai. The South Korean automaker was back to nearly full domestic production by the end of March after recovery from the February effects of the pandemic. The South Korean automaker was able to initiate the startup because of the recovery in South Korea and also because parts supplied by China and other Asian suppliers were back online as those countries recovered from the pandemic. And Hyundai began shipping their popular Tucson SUVs to the US – 33,990 vehicles, a 4.3% increase over 2019, according to a Reuters report.

But at that moment there was no market in the US for SUVs or for that matter anything else as the doors of car dealerships were locked, layoffs rampant and stay at home orders issued in many states. The vehicles like those from other foreign automakers were being shipped to a market-less market in the US. The result was PCTCs parked off West Coast ports loaded with vehicles that had no place to land because all the available tarmac ashore was jammed with undeliverable vehicles. The auto supply chain was clogged with vehicles as there was no outlet because sales had all but dried up.

Autoports – Supply and Demand in 2020

The Port of Hueneme, which handles more than 340,000 vehicles annually along with a strong mix of reefer cargo such as bananas, and like other West Coast auto ports, suffered from the collapse of the auto market. CEO & Port Director of the Port of Hueneme Kristin Decas outlined the problems nearly all auto ports were navigating in a May interview in the port’s house blog, “There are two parts to this equation, supply and demand. The past month we have been helping our customers store additional automobiles that were not being sent to dealerships as a result of the stay-at-home orders in several states. Now, as the dealerships re-open and consumer demand comes back up gradually, we are still going to see a reduced level of shipments to the Port from that segment until the manufacturing plants can resume production and re-establish their supply chains.” Fortunately for Hueneme, during the pandemic people are still eating bananas and other perishable commodities which has helped offset the downturn.

Of Course, Hueneme Wasn’t Alone.

Port of Portland, Oregon, another major West Coast auto port that handled over 340,000 units in 2019, is another example of the impacts of the pandemic on auto imports, as the port handled 22,732 vehicles in April which dropped to 12,803 in May followed by 10,319 in June. Farther north on the West Coast the Northwest Seaport Alliance (NWSA) reported that through August 2020 the ports had handled 91,874 units compared to 131,167 units for the same period in 2019 – a 30% drop.

The result was similar on the East Coast as the Port Authority of New York/New Jersey (PANYNJ) reported, “Autos moved through the Port of New York and New Jersey totaled 37,888 in August, a decrease of 28.2% compared to August 2019.”

One of the few ports recording an uptick in auto handling this year was the Georgia Ports Authority (GPA). The GPA, whose main ro/ro facility is located in Brunswick, reported “in March [the GPA] handled 66,318 units of cars, trucks and heavy machinery, an increase of 25.7% over the prior year. For the fiscal year through the end of March, Georgia’s ports have handled 505,192 ro/ro units, an increase of 5% or 24,143 units compared to the same period last year.”

US OEMs – the Ugly, the Bad, the Good and Out of this World

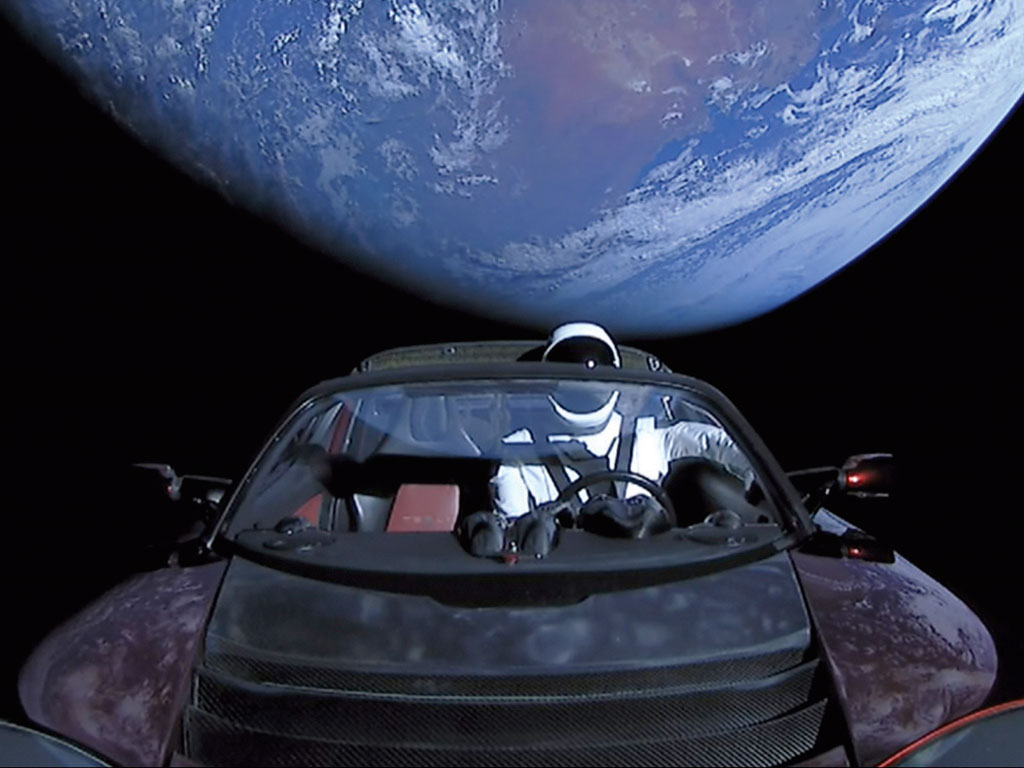

Although the ports were hard hit, the real carnage is with OEMs themselves. Sales for nearly every automaker are off through three quarters…but some are better off than others. For example, there were some ugly numbers as Nissan through three quarters was down 25% and Jaguar Land Rover 22.8%. A majority of the automakers are having a bad year, off in the teens or below like BMW (-10.2%), Fiat Chrysler Automobiles also (-10.2%), Volkswagen (-10.5%), Toyota (-11%), Honda (-11.8%) GM (-9.9%), Subaru (-8.8%) Daimler (-5.7%) or Ford (-4.7%). And a few automakers have more than held their own, like Volvo (11.1%), Mazda (6.9%) and Hyundai (0.9%). And then there is out of this world results – just like Starman piloting his Tesla Roadster passed Mars, sales for Tesla, Elon Musk’s EV automaker, are up 154.7% in the 2020 3rd quarter compared to the same period in 2019.

Tesla’s ridiculous results in the midst of the pandemic are indicative of a few trends that are reshaping the auto market and could have a profound long-term impact on auto logistics. First and foremost, EVs are now emerging as a mainstream product in the US – the world’s largest car market. How this shift will impact auto supply chains and indeed global auto sales patterns is yet to be determined but the auto paradigm may have already been altered.

Twang - Auto Demand Snaps Back

After the downturn, OEMs were able through a variety of incentive based sales to clear the inventory backlog of vehicles and by June auto sales had surprisingly begun to snap back. After bottoming out in April at sales of 512,122 units, May numbers rebounded to 1,181,756 and in June 1,214,706. Both months were behind the sales pace set in 2019 but in September unit sales hit 1,370,243 unexpectedly eclipsing the 2019 September figure of 1,282,714 [latest month for which data is available].

Randy Fischer, a senior analyst at the Port of Portland Oregon, said of the ‘rubber band’ effect, “We have seen both imports and exports increasing and for the first time in months, September volumes looked like a typical month in 2019. With production playing catch up to refill showroom floors and Covid-19 restrictions easing, consumers are making their way back to dealerships. While it’s difficult to see fleet sales returning as quickly, current volumes and short range forecast looks strong with consumers driving the markets return to normalcy. “

Of course, this bounce back could be temporary – a short term reaction to pent up demand – and as Wallenius Wilhelmsen proffered in their report, “Light vehicle sales could take until 2024 to recover to 2019 levels.”

There are a number of big questions yet to be answered on whether the 2020 ‘twang’ propels the auto industry into another protracted period of growth in the US and globally.

Among the many ‘big’ unknowns, is how Mexico’s automakers will fare both in the short term, dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic and long-term with the implementation of the USMCA. The vast entanglement of US-based OEMs and Mexican automakers almost makes it impossible to separate their interests. And some trepidation comes with Mexico’s number thus far in 2020. In the latest reports, Mexico’s auto exports are down -13.1% over a year earlier to 247,126 units in September 2020. This is after dropping 8.6% in August. Among major exporters, shipments fell from General Motors (-2.6% – 67,800), Ford Motor (-99.1% – 200), Nissan (-3.3% – 34,100), Volkswagen (-41.9% – 24,200), KIA (-18.1% –14,900), Audi (-3.4% – 14,800), and Honda (-34.2% – 9,700).

This isn’t to say some Mexican OEMs’ exports aren’t up in 2020. Fiat Chrysler Automobile (FCA) is up 3.1% to 45,100 units while Toyota is up almost 3% shipping 19,000 units. But overall the Mexican recovery still looks to be some ways off.

Which begs the question, will the snap back of the US auto industry continue into the winter of 2020 and 2021? Or with the pandemic still raging and economic uncertainty all around, will the full recovery of the US auto market also require more time?