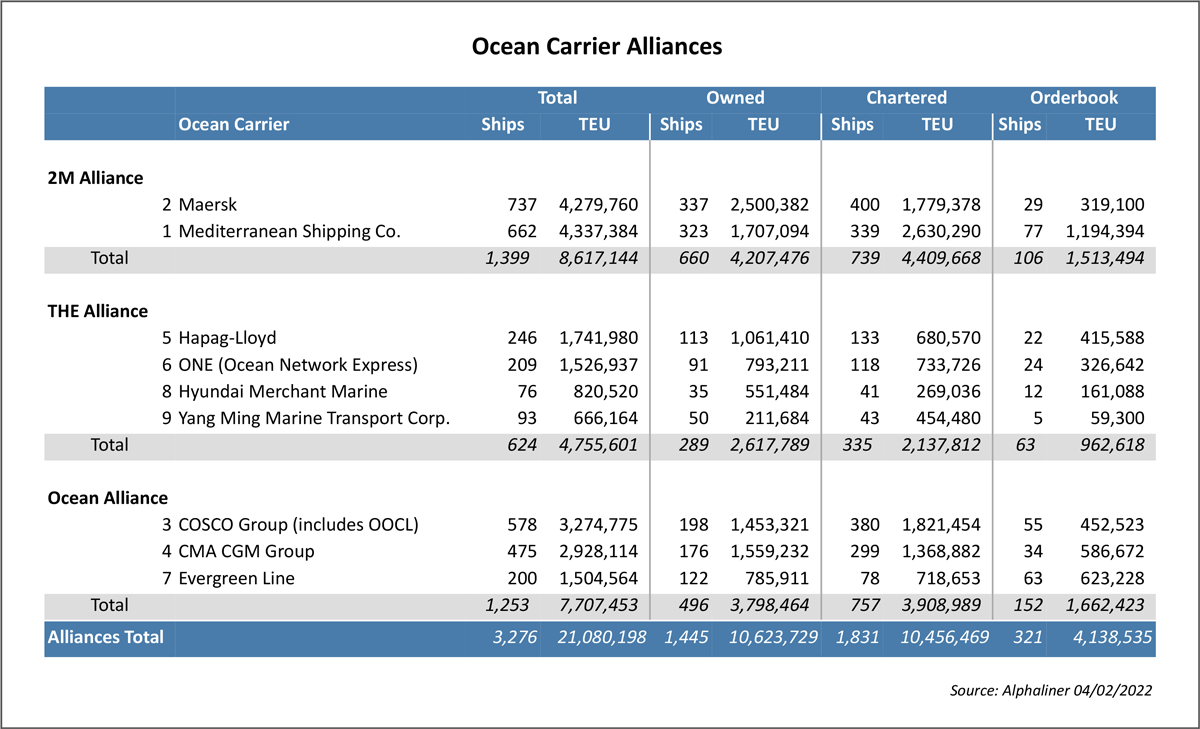

The ocean carrier alliances control over 80% of the trade. But challenges both from ongoing supply chain disruptions and a new regulatory agenda could alter the way alliances operate.

Until recently, most commentators from outside the industry had never heard of shipping alliances. Their names rarely evoked a stir. But like many other things that have occurred since the COVID-19 pandemic began, so has a recognition of global shipping alliances. After all, the real structure of the global supply chain is built around these ocean carrier alliances.

So, what does an alliance do? A succinct answer might be the alliances organize ship movements. In a sense, the real structure of the global supply chain resides in the ocean carrier alliances.

From an organizational perspective, it is the service schedules of the various steamship lines within the big three ocean carrier alliances that provide the framework for the global supply chain. Such collaboration between ocean carriers isn’t new. In some ways, the new generation of shipping alliances is the successor to the shipping conference system of the 1880s. But an agreement to collaborate of space and other backroom services doesn’t extend to freight rates – an important distinction when it comes to anti-trust regulatory issues. And up until fairly recently, carrier alliances didn’t wield the same commercial power they do today and didn’t attract the same level of scrutiny. Not to say there weren’t investigations, there were. But with so much competition among the ocean carriers, the debate was more over incidents of abuse rather than a need to overhaul the entire ocean carriage system. The ocean carriers simply weren’t making money and “competition” for freight was ferocious – putting to rest any “anti-competitive” considerations.

That all changed with the Hanjin bankruptcy in 2017. The South Korean carrier’s $10 billion bankruptcy shook the industry like no other failure before it. There was a realization that no ocean carrier was too big to fail. And the Hanjin bankruptcy triggered a massive consolidation of ocean carriers and in turn a parallel consolidation within the ocean carrier alliances.

Slices of a Pie

The feature that makes the ocean carrier alliance work is the contribution of ships and slots that each carrier makes to the alliance. It is from this basis that slices of the cargo pie are divided. As an industry veteran that held executive positions with a number of containership carriers, Greg Tuthill, now the chief commercial officer at SeaCube, a container leasing company explained, “It’s all based on the basic slot agreement, which is tied to how many assets you put into the alliance… The way its partition is typically based is on how much tonnage you are contributing to the alliance…There’s a demand forecasting process that each alliance goes through… (And) every alliance member has their right to go ahead and declare what they want… there are some nuances to the extent that some are getting more than what they contribute, some want less than what they contribute. But generally speaking, alliance structures are tied to contribution [of ships and slots], similar to some of the other asset type models.”

While the overall model is fairly straight forward, the day-to-day “network” management of the system can be quite complex. In the case of North America, the high value, low volume inbound freight, particularly from China and Southeast Asia is balanced against the exports of low value but heavy freight. The inherent system wide imbalance in terms of both dollar value and containers complicates vessel rotations and container repositioning.

Alliances and the Unallied

Ideally, alliances like to have similar vessel sizes or classes, operating with their networks. But one-size doesn’t always fit all, as ports and terminals often can’t accommodate the vessels that an alliance wants as its linehaul ships. So, what happens when an alliance member wants to deploy a class too large for a port or terminal because of a draft or equipment considerations? That port is likely dropped from the rotation. Even in cases where the ship can be handled – but not optimally – the port is likely to be the first bypassed or subject to the industry’s well-used oxymoron “blank sailings”. The reasoning (or at least the most often spoken reason) for the bypass or even a port being blanked is usually because the schedule has deteriorated, often because of congestion at a previous port and to make up time, the ship calls next port in the rotation. One port executive asked about why his port in particular, was blanked out so often, simply answered “the alliance.” Offering that while some alliance members might want to make the call, the demands of a preeminent carrier in the alliance, dictated the bypass.

Yet for an industry that is built on the modicum “keep the asset moving”, the next port-of-call isn’t necessarily the fastest or least congested. But in nearly every instance, it is a hub port that best fits the carriers’ needs inherent to the container flow of high value inbound and low value outbound cargo imbalance conundrum. And among these priorities is the repositioning of containers for return (often to Asia).

The ocean carrier alliances, like other parties immersed in the supply chain, were ill-prepared for the disruptions caused by the COVID pandemic. The stuttering movement of boxes from China has exacerbated the inherent problem with imbalances and caused massive pile ups at West Coast and now East Coast ports. The size of the Chinese ports is so much larger that when they release the pent up volume it is like the opening of a dam with the downstream barriers too small to handle the flood of containers.

A New OSRA and the Alliances

Fair or unfair, both American ports and shippers who rely on the alliance ship calls have been unhappy with the current state of affairs. This has culminated in a bill to “update” the Ocean Shipping Reform Act (OSRA) of 2022, which was passed by the Senate on March 31.

From a port perspective, an alliance puts a lot of eggs (or steamship lines) in one very fragile basket. The loss of an alliance call can be devastating to a port as it is the equivalent to losing a number of lines without the former advantage of being able to salvage the situation by appealing to another carrier.

And from the shippers’ perspective the alliances have failed to deliver the goods. And demurrage and detention fees have become a sore spot with shippers, considering that Sea Intelligence’s Global Liner Performance was up 4 percentage points in February to 34.4%. Few shippers can take much solace in the fact that vessels on time arrivals are now down to 7.11 days.

Added to the poor performance of ocean carriers within the alliances is the fact that exporters have been unable to secure slots for their products. As the ocean carriers have prioritized returning empties to Asia over filling boxes with often less valuable export commodities. This has also contributed to shipper discord. American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) President Zippy Duvall commenting after the Senate approval of the OSRA bill, noted Farmers have lost out on up to $4 billion in agricultural exports because of lack of access to export containers, record shipping costs and harmful surcharges. Limited trade has also hampered farmers’ ability to get crucial supplies like fertilizer at a time when supply chains are already stressed.

The ocean carriers dispute the finger being pointed at them and the need for an overhaul of OSRA. John Butler, President and CEO of the World Shipping Council said in rebuttal to the announcement of the Senate vote on OSRA, “The truth is that with demand for ocean transportation services into the U.S. at record levels, market dynamics are influencing prices – not carrier alliances. [Editor Italics] These vessel sharing agreements (VSA) are purely operational compacts that enable carriers to share space on one another’s ships, which increases efficiency and supports more service to more ports than would otherwise be the case. Importantly, the operational agreements do not include commercial cooperation. Each member of a VSA or alliance determines its own commercial terms, including prices, which are not discussed between alliance members. Every VSA is filed, reviewed, and continuously monitored by the FMC.”

Certainly, there is some truth in Butler’s remarks that the alliance structure isn’t wholly to blame to the disruptions to the supply chain. Still the tripartite structure of the alliances operating global liner shipping is impacting competition and begging regulatory intervention – and regulations, like the flu, are highly contagious.